Activist art collective Liberate Tate’s “creative disobedience”

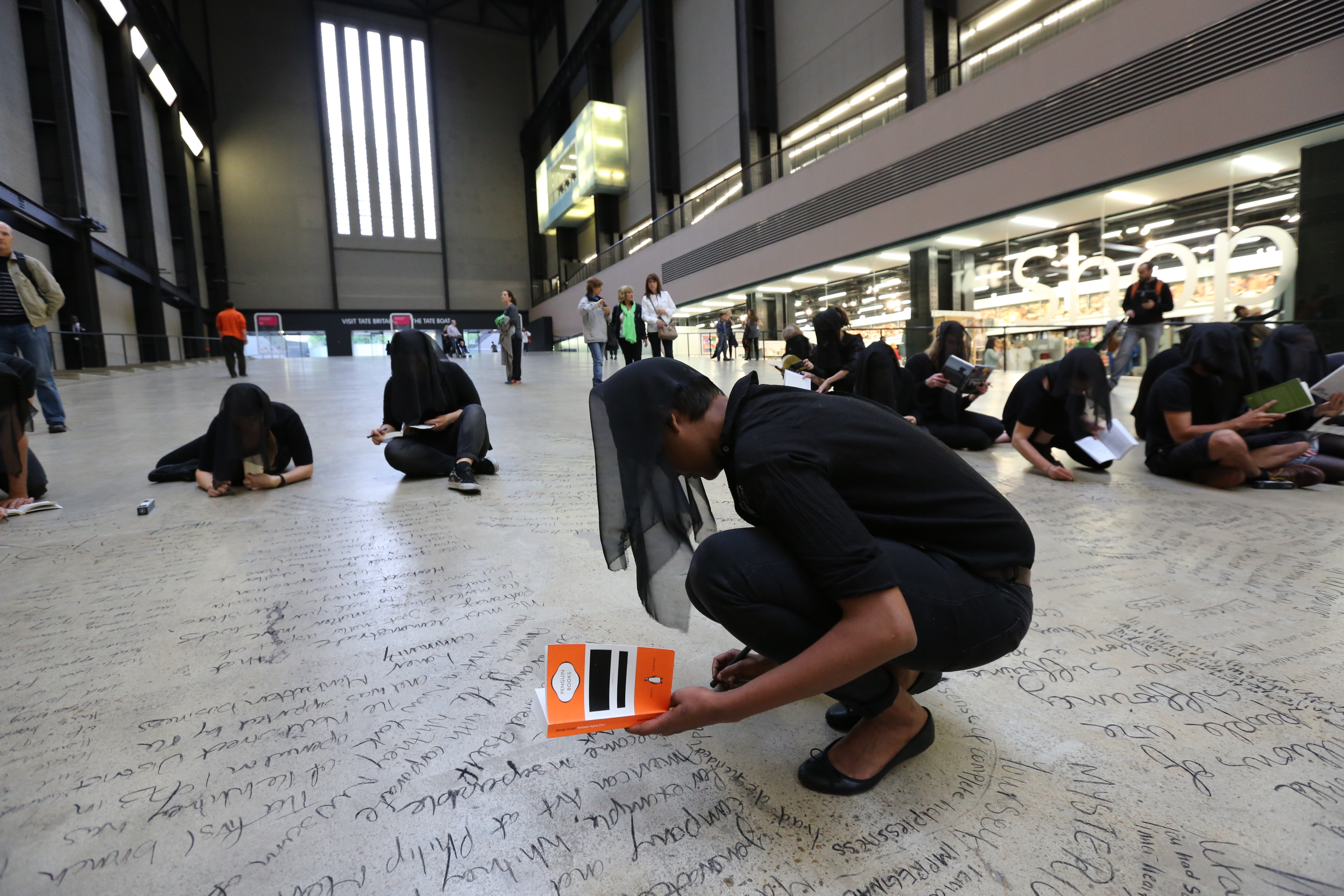

In March 2016, multinational oil and gas company BP announced it would end its 26-year sponsorship of the renowned British cultural institution, Tate. For activist art collective Liberate Tate – formed shortly after the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010 – this was the culmination of six long years spent campaigning Tate to drop its oil company funding through a series of nearly 20 unsanctioned performances, interventions and protests inside Tate Modern and Tate Britain. Ranging in size and scale, these performances – or acts of “creative disobedience”, as Liberate Tate calls them – included a calculated ‘oil spill’ at the Tate Summer Party (Licence to Spill, 2010); the public presentation of a 16.5-metre, 1.5-tonne wind turbine blade submitted as a ‘gift’ to Tate’s permanent collection (The Gift, 2012); and a 25-hour ‘textual intervention’ that saw the floor of Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall covered in charcoal commentary relating to themes of art, activism, climate change and the oil industry (Time Piece, 2015).

In a world where arts funding is increasingly tenuous, corporate sponsorship is often a necessary part of the equation. But what might ethical funding look like, and who gets to decide what it constitutes? In Not if but when: Culture Beyond Oil (2011) – a collaborative publication by Liberate Tate, arts and research organisation Platform, and activist group Art Not Oil – Platform’s Jane Trowell maps the shift in narrative around ethical funding from the mid-’90s until recently, concluding that, “Now more than ever before it is critical to put ethics, aesthetics and corporate sponsorship under the spotlight.” In Australia, the conversation around ethical sponsorship came to a head in 2014, when exhibiting artists successfully boycotted the Biennale of Sydney that year on account of its sponsorship by Transfield Holdings (the company whose former subsidiary Transfield Services, now separated from Transfield Holdings and rebranded as Broadspectrum, manages Australia’s offshore immigration detention centres in Nauru and Manus Island). For Liberate Tate, an important element of the collective’s resistance was the combination of performance and direct action in the name of opening up a more public, more transparent conversation around corporate sponsorship and the arts. Ahead of her trip to Australia, I caught up with Liberate Tate co-founder Mel Evans to chat about ‘Big Oil’, ethical sponsorship and the power of performance.

Sara Savage: Take me back to the inception of Liberate Tate. How did the collective come about?

Mel Evans: Two things happened in quick succession. Firstly, some friends of ours [The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination] were invited to do a workshop at Tate [Disobedience Makes History, 2010] in which there were elements of confrontation and activism within the program. The workshop facilitators were warned by Tate staff members that it would be inappropriate to mention the sponsors as part of the workshop, which was kind of like a red rag to a bull. So at the workshop, the group decided to put up the words ‘Art Not Oil’ on one of Tate Modern’s windows – it’s actually the name of a pre-existing project surrounding oil and the arts, but the words were used in the workshop too. Not long after, the Deepwater Horizon disaster happened, and the importance of confronting BP’s power in the cultural sphere suddenly became even more pressing than it already had been.

But it was the Tate summer party in 2010 that was the real birth of our project. Our friend, the artist Peter Kennard, offered us his tickets to go along to the annual event, which that year was celebrating 20 years of BP sponsorship, and which after the Deepwater Horizon disaster to us just seemed highly inappropriate. So we arranged a series of ‘spills’ at the party, where myself and another woman arrived in bouffant floral dresses with 10 litres of molasses under our skirts and spilled them in the centre of the party. That’s really when we started to appear in the media and the public conversation really kicked off in a new direction.

SS: Compared to other mediums, what do you think is the power of performance as a form of direct action?

ME: I think it’s about the parallels between them. I have a theatre background, so I’ve always been coming from performance and from a place of centring the body. In live art, the vulnerable body is often the centre of performance – a durational performance might be about how long the body can last, or the repetition of a certain act, or certain things being drawn on the body. At the same time, the vulnerable body is such a huge part of the philosophy of non-violent direct action, like putting your body in the way of a digger or a truck or an oil tanker. There’s also the element of knowing that a performance has to remain responsive. I think it does come down to the body, though; bodies have always been hugely important in Liberate Tate’s work, whether it’s been a performance involving five people or a hundred people. And when the site of intervention and the target of the campaign is a public gallery that’s free to access, that’s somewhere we can get in! [Laughs.]

SS: I imagine it’s often quite a process getting everyone into the gallery.

ME: We’ve had quite a journey smuggling things in over the years. We’ve met Tate staff in the toilets to do a quick handover of big bags of molasses, we’ve had 64m2 of cloth smuggled in in baby strollers … but the easiest thing to get in is bodies and for that reason they’re the core material of our work. It’s also about people and about community-building, and opening up a space where artists and activists can come together and learn from each other. I think Liberate Tate’s work has really been a place where artists who’ve never taken part in protest or direct action have tried it out – it’s been quite a transformational process for artists, and for activists it’s a way of doing things differently than perhaps they usually would. It’s also about the live moment and not necessarily about creating something that we could repeat.

SS: There’s also something to be said for the power of performance in allowing the audience to slow down and consider how they actually feel about something.

ME: Definitely. Often people ask us why the gallery staff don’t just stop our performances immediately – and we have had strong reactions from security in some performances – but in that art space, the gallery space, where people are performing, there’s often the sense that maybe it’s something that’s been programmed. We’ve even heard staff checking in with each other, like, “is something going on in Gallery B right now?” [Laughs.] Because when someone’s performing, you don’t want to interrupt them. It maintains itself in that way and allows for much more unexpected things to happen, and for us to continue performances. I mean, for one performance we managed to stay in Tate Modern for 25 hours overnight [Time Piece, 2015].

SS: How does that work? How did they not remove you? And did anybody get arrested?

ME: No. It was threatened that we would, and we were prepared to – we started off with 100 performers and within that we had the direct action organising and preparation as well as the durational live art preparation. We had legal support ready if we needed and we’d had lots of conversations with people about what they felt and who would need to leave if there was a risk of arrest and who would be okay to stay and continue the performance.

SS: In the current political climate of Brexit and Trump, do you think we’re seeing a groundswell of political activism among people who wouldn’t normally speak out?

ME: In a way, yes. I think that’s something we saw after all the global marches against the Iraq War – for me that was a really formative time. I was 19 when the Iraq War began in 2003 and I remember the experience of going to protests and believing that those protests – some of the biggest the world’s ever seen – would stop it. Then came the experience of watching bombs drop over Baghdad and realising we hadn’t stopped anything at all. That really challenged me and informed a lot of my thinking around what kind of action works. I think the current political situation asks a different set of questions around what makes social and political change not only happen, but what makes it sustainable? A big question right now surrounds the women’s marches against Trump – was it too narrow that it was a women’s march? Why wasn’t the racism and xenophobia around Trump and Brexit more named in this kind of global coming together?

I don’t want to water down the enthusiasm, but at the same time I don’t want to say this is a big moment of change. I’m also concerned that it’s a very high-pressure situation right now, where a lot of people are in pain. Putting high demands on what those people can achieve right now is an additional pressure that’s quite important to address.

SS: It’s funny when you hear some people, particularly public figures, proclaiming that ‘great art’ is going to come out of this particular political moment, as if it isn’t a huge luxury and a privilege to even be able to say that.

ME: Right, exactly. I mean, I’m all up for wonderful art, but I want it to actually affect the situation too. I want to it to affect change. I don’t just want it to be a dissociated piece of amazing art.

SS: Soon you’ll be visiting Australia as a part of ART+CLIMATE=CHANGE 2017. How much have Australian issues popped up in your research on sponsorship and the arts? In your book Artwash: Big Oil and the Arts (2015) you mention the December 2013 issue of Artlink magazine, entitled ‘Mining: gouging the country’, which explores the tensions between mining operations and arts patronage in Australia, as an influence.

ME: The first and only time I visited Australia was when that issue of Artlink came out. It got me interested in the work of [Yamaji artist and writer] Charmaine Green and her specific critique of companies mining Aboriginal land at the same time as sponsoring Aboriginal art. There’s also [Brisbane-based activist group] Generation Alpha, who actually got in touch with Liberate Tate when they were protesting in Brisbane. And then of course there’s the Transfield case, at which time as a collective we wrote a statement of solidarity in support of the artists boycotting the Biennale of Sydney [in 2014]. We took a lot of inspiration from that – when they were successful, Liberate Tate thought, okay this can actually happen!

Coming to Australia, and being invited to speak at events there, I do have to consider that I’m a white British person and I have to continually ask myself, “How is our relationship decolonial?” I have to come over in a way that’s humble and willing to learn, and focus on working together to heal the wounds we’ve inherited rather than to consolidate power dynamics that are a part of that. I do think it’s important though to trade stories, share skills, support each other and bring people together – it’s all a really important part of shifting the narrative. But it’s certainly not something that’s uncomplicated.

*

This article is taken from Assemble Papers Issue 7: ‘In/formation’. Head to the Liberate Tate website to see more of their ‘creative disobedience’, or catch Mel Evans at ART+CLIMATE=CHANGE 2017.

Original image: Human Cost (2011), Duveen Gallery, Tate Britain, took place on the first anniversary of the BP Gulf of Mexico disaster. Photo: Amy Scaife.