How Australian suburbs could create community

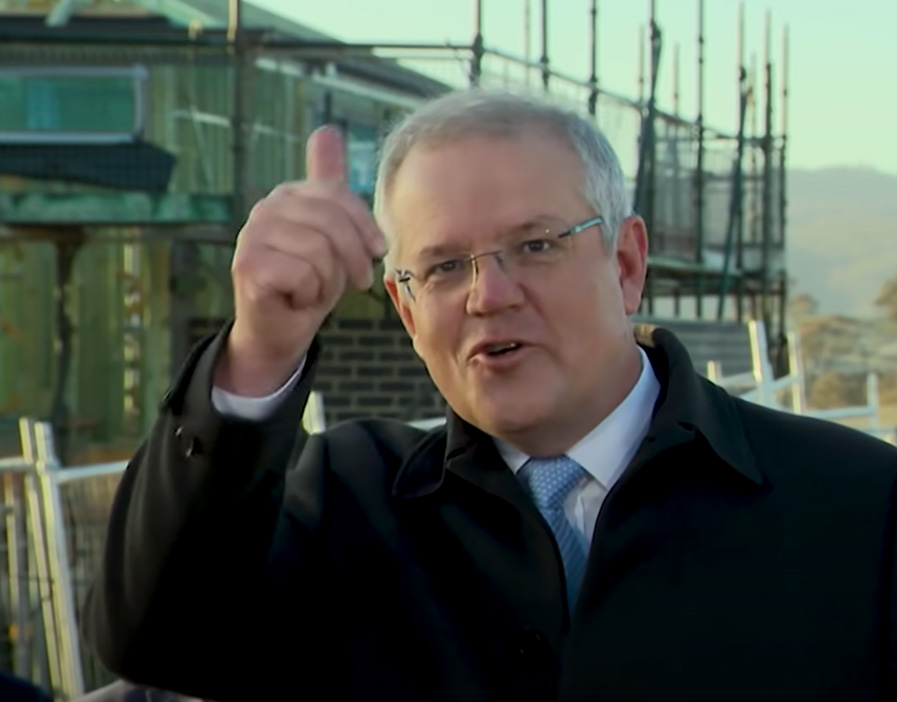

Morrison on the Verge

“Can everyone get off the grass, please?” a man yells, pointing at his front yard. “I’ve just re-seeded that.” An unremarkable appeal, except that it is made to the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, in the middle of a press briefing orchestrated to have homes under construction as the backdrop. Morrison then encourages the media pack toward him, gives the exasperated man the thumbs up and tells him, “All good!”, before continuing with his speech.

It’s a funny clip, and like the best funny clips, it reveals some deeper truths. That the man doesn’t hesitate to yell at the highest elected official in the land shows a wonderful lack of deference to authority, that great Australian trait, and surely a sign of a healthy democracy. And in Morrison’s quick understanding, we can also glimpse the invisible boundaries that govern the suburbs. The grassy verge is not fenced – it’s continuous with the public footpath – but it’s undoubtedly private. Not even the Prime Minister can cross this invisible line. With Morrison and his media pack pressed between the seeded lawn and the road, this exchange also reveals the paucity of the public realm in much of Australia today.

Morrison was speaking in Googong, a new suburb under construction near the ACT–NSW border, a 20-minute drive from Parliament House. Under a big sky, surrounded by rolling hills and mature trees, it appears to be one of the more desirable planned developments being built today. The press release proclaims Googong “sets a new benchmark for socially, economically and environmentally sustainable greenfields communities,” highlighting an integrated water recycling system, and “landmarks celebrating the region’s Aboriginal and colonial history.” And yet the pattern of development follows closely the template used all over the country: of large houses on small blocks, with small setbacks or gaps between, strung together along strips of tarmac. Colourbond hipped roofs designed by algorithm appear in satellite imagery like clusters of ancient ziggurats. In seeking to maximise the private domain, the public realm has been squeezed out. The whims of the consumer are satisfied at the expense of society. It is in the public realm where we can address the greatest challenges that we face together: tolerance, community, loneliness, care and support. What might a suburb built around these goals look like?

Nolli in Googong

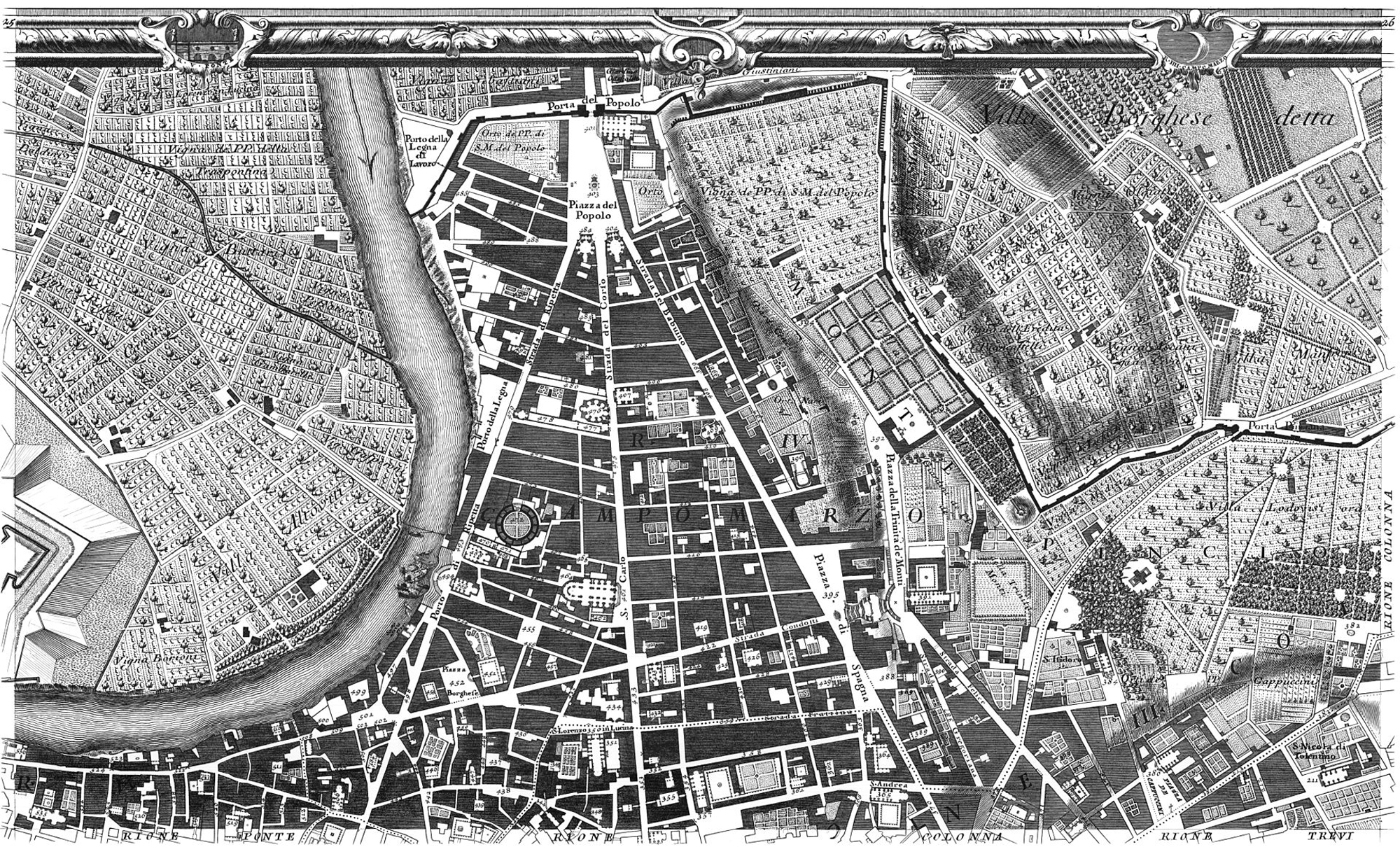

The extent of the public realm is the subject of one of the most famous drawings in the history of architecture. Known as the Nolli map, it is an incredibly detailed map of Rome drawn in 1748 by Giambattista Nolli, an Italian architect and surveyor. The map is drawn in stark figure-ground, where the buildings are shaded black, and the streets are white. Most fascinating is that the interiors of public and religious buildings are shown in the same white as the street beyond, punctuated by colonnades holding up the roofs. What is inside or outside is of little importance to Nolli; what matters is where you can walk as a citizen. The city is exposed as if by x-ray, revealing a continuous public realm, from the narrow back alleyways to the dome of the Pantheon.

What would Nolli make of Googong? Having spent eight years pacing the narrow streets of ancient Rome, he would no doubt be astounded by the space and generosity of the typical subdivision of detached homes. “To every family a castle! What wealth!” Surveyor’s chain in hand, he would pace the street, sketching out a wide band of white space extending from front door to front door, taking in the verges, footpaths, parking lanes and roadway, with the private gardens beyond forming a black boundary. But after being accosted by a homeowner and hooted at by a driver, Nolli might reconsider the shading of this apparent public realm. Despite the ever-present horizon, with the roadway too dangerous to walk on, and the front verge off limits, this grand suburban boulevard is reduced to a thin stripe of white – the footpath – amongst a sea of black shading. As residents enter their homes by driving straight into their garages, Nolli would rightly ask, “Where is the space that is ‘ours’? Where is the space of democracy? Where can I be a citizen?”

Why Does this Matter?

An urban structure that discourages chance encounters prevents the kinds of spontaneous mutual support that form the basis of resilient places. Who can you turn to for a last-minute babysitter, an after-school playdate or help carrying in the shopping? Without these informal connections, our neighbourhoods become brittle, unable to respond to crises, and prevent us from caring for each other in times of need.

This tendency is being further reinforced by technology. Seemingly innocuous inventions like the automated supermarket checkout or Uber are abstracting away the micro-encounters of daily life. Handing over change or discussing a route are some of the few moments where we are required to engage with somebody different to ourselves.

This situation has become further apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as we look at each with narrow eyes from behind our face masks, passing at a distance. But in other ways, the pandemic has helped. With many people now working from home, no longer commuting to the centre, they are more present in their neighbourhoods, able to invest in these local relationships.

Despite this small glimmer, the physical structure of the suburbs still exerts a negative pull, further widening the gaps between us, leading to a public sphere that’s further divided. How could we reimagine these spaces as places of encounter? As places of conviviality? How can we glue these gaps back together?

“The house in this new neighbourhood must reorient itself toward the public realm.”

Public Life as Glue

This glue is public life itself. The daily encounters with people who are different to us in small and large ways build a resilient society. As writes Jane Jacobs, the most passionate advocate for the public life, “Lowly, unpurposeful and random as they may appear, sidewalk contacts are the small change from which a city’s wealth of public life may grow.” But Jacobs’s views were shaped by New York’s Greenwich Village in the 1960s, a dense and diverse working neighbourhood, combining families, shops and industry, all folded on top of itself in a vibrant and dynamic whole. This is the opposite of the suburbs, with Jacobs even warning that “I hope no reader will try to transfer my observations into guides as to what goes on in towns, or little cities, or in suburbs… they are totally different organisms… [and] we are in enough trouble already.”

Ignoring Jacobs’s warning, we can instead imagine the potential for the suburbs to provide a meaningful public life. By reimagining the home, the street and the neighbourhood, we can reconfigure these places to be equally diverse and resilient.

The Home

The suburban house today is defended from public life by turning away from the street, guarded by a double garage and a deep setback of unused terrain. The typical plan will also place the living room to the rear, and a bedroom facing the street, further preventing casual encounters with passers-by. The house in this new neighbourhood must reorient itself toward the public realm.

A further blurring of this distinction between public and private can happen with programs. We have long denied the central role the private home plays as a place of work – not only the largely unrecognised and highly gendered work of running a household or raising children, but also the many small businesses run from front rooms and garages: independent trades, yoga studios, music lessons, shared childcare and so on. These are critical sources of revenue and employment, particularly in places that are remote from centres of activity. How might we encourage more of this to take place?

The viability of many of these businesses, particularly those serving the immediate neighbourhood, depends on a level of density greater than that of many suburbs today. This can be increased with new typologies of housing – the terrace, or back-to-back – and with the spontaneous infill of backyards with accessory dwelling units (granny flats), multi-generational housing, or sub-divisions. A piecemeal approach, led by homeowners, not developers, can lead to densification without displacement of the people and qualities that make suburbs desired in the first place.

The Street

Returning to our Nolli map of the suburban street, we can see this thin, white line of footpath as the only truly public space of encounter. How might we reimagine the suburban street to maximise this space? How can we stretch it spatially and engender a collective sense of ownership and responsibility?

We can begin by reclaiming front yards, expanding the width of the footpath to create more useful zones for playing or relaxing. We can create zones of shared productive gardens by taking down fences between properties. And we can even begin to reclaim space from the roadway by moving cars out to the ends of the street, digging up the road and creating a new space for playgrounds, cafes, trees, outdoor gyms, cafes, even swimming pools – a distributed chain of public amenity.

This is a space for those who currently do not have a place in the suburbs: children and the elderly, and their parents and carers. It’s a space for cooperative activities, addressing isolation and loneliness. A safe space owned by the street.

The Neighbourhood

The neighbourhood town centre or high street has been struggling in recent years, their vitality eroded by the rise of Amazon and big box stores and a growing concentration on the city centre. But with the shifting economic geography post-pandemic, could these places become newly viable business propositions? And more than that, could they also serve as vital spaces for civic and social life?

It’s not nostalgic to want these qualities from a high street. Local businesses are invested in local places, and their dollars can stay in these local places, through revenue, taxes, employment and, critically, investment. If this value is captured and reinvested over time, these places that have for decades been neglected will all of a sudden start to get better, not worse, creating more opportunities and skills.

Local economic engines can be used to start to repair the loss of assets and services in recent years or to build them where they have never existed. A local library offers more than books: it hosts local meetings, after-school clubs, job notices and even toy libraries. Combined with hub workspaces – for those working from home but still keen to get out of the house – these places could form distributed networks of care and support, bolstered by spaces of public celebration: cinemas, theatres, good pubs. In other words, they will become centres of wider economic and social ecosystems.

* This is more than a design project; it is a social, political, environmental and ideological one. It seeks to burst the illusion of individualism that the suburbs were founded upon and create a new consciousness of our shared public lives. It reminds us that we are all tethered to each other in a common project of living and the more that we can enlarge that realm, the better prepared we will be for the challenges of our futures.

So when the next prime minister makes an announcement from a suburban street, instead of being asked to ‘get off my lawn!’, she might perhaps expect a friendly wave.

This piece is part of Assemble Papers 13 Mind the Gap, published at the beginning of February 2021. Find the print version of Mind the Gap at cafes across Melbourne, or order a copy from our webshop and pay only postage costs.