Tracing the garbage trail around the globe

In our latest instalment of the ‘Circular Thinking’ series, we are going global. Where does our waste go? Does our recycling even get recycled? And what has China got to do with it? Professor of international urban politics at University of Melbourne, Michele Acuto, is here to help.

The travels of trash are far from a simple matter, in an age where more than half of the world lives in cities and more than 740 million containers cross the oceans every year. Does our waste go to China? And if not, why are we in a ‘waste crisis’? The geopolitics of garbage matter: if we want to mindfully dispose of our crumpled milk carton or the pizza box from last night, it is important not to think of waste as a simple local matter. Can we solve this crisis by switching to a ‘circular economy’? Maybe. But to understand the global economy of waste, the management of garbage that transcends international borders, we must go beyond the image of the circle.

Australia is currently facing a waste crisis that has seen numerous Australian local authorities dumping recyclables into landfills, emergency interventions by city councils and state governments, and even a new national waste policy. This has, for the most part, been the result of a new policy put in place by China as of January 2018. The Chinese ‘National Sword’ programme (complemented by an even stricter new customs inspection program called Blue Sky 2018) banned 24 categories of solid waste and instituted a new 0.5% contamination threshold for all waste imports. This, in turn, halted the export of more than 1.25 million tons of Australian recycling each year – approximately one-fourth of Australia’s global export of waste and 99% of Australia’s recyclables exported to China.

The switch was sudden and highly impactful. The Financial Times reported, for instance, that China and Hong Kong went from buying 60% of plastic waste exported by G7 countries during the first half of 2017, to taking less than 10 percent during the same period a year later. The Australian recycling system was seemingly unable to cope with this change. And Australian policy-makers are waking up to the global dimensions of waste management: at present a $47 million support package is being funded by the New South Wales Government’s Waste Less, Recycle More initiative, to help local government and industry “respond to global recycling changes”.

Global waste is no small business. The latest World Bank estimates tell us that 2.01bn tons of municipal solid waste were generated in 2016 – a figure expected to grow to 3.40bn tons by 2050, fuelling what is already a $433bn industry. More than 270 million tons of waste are recycled across the world each year. Every year there are at least 700 million tons of waste recycled globally as ‘secondary commodities’ – such as plastic, textile and paper – in what is now a $200bn business.

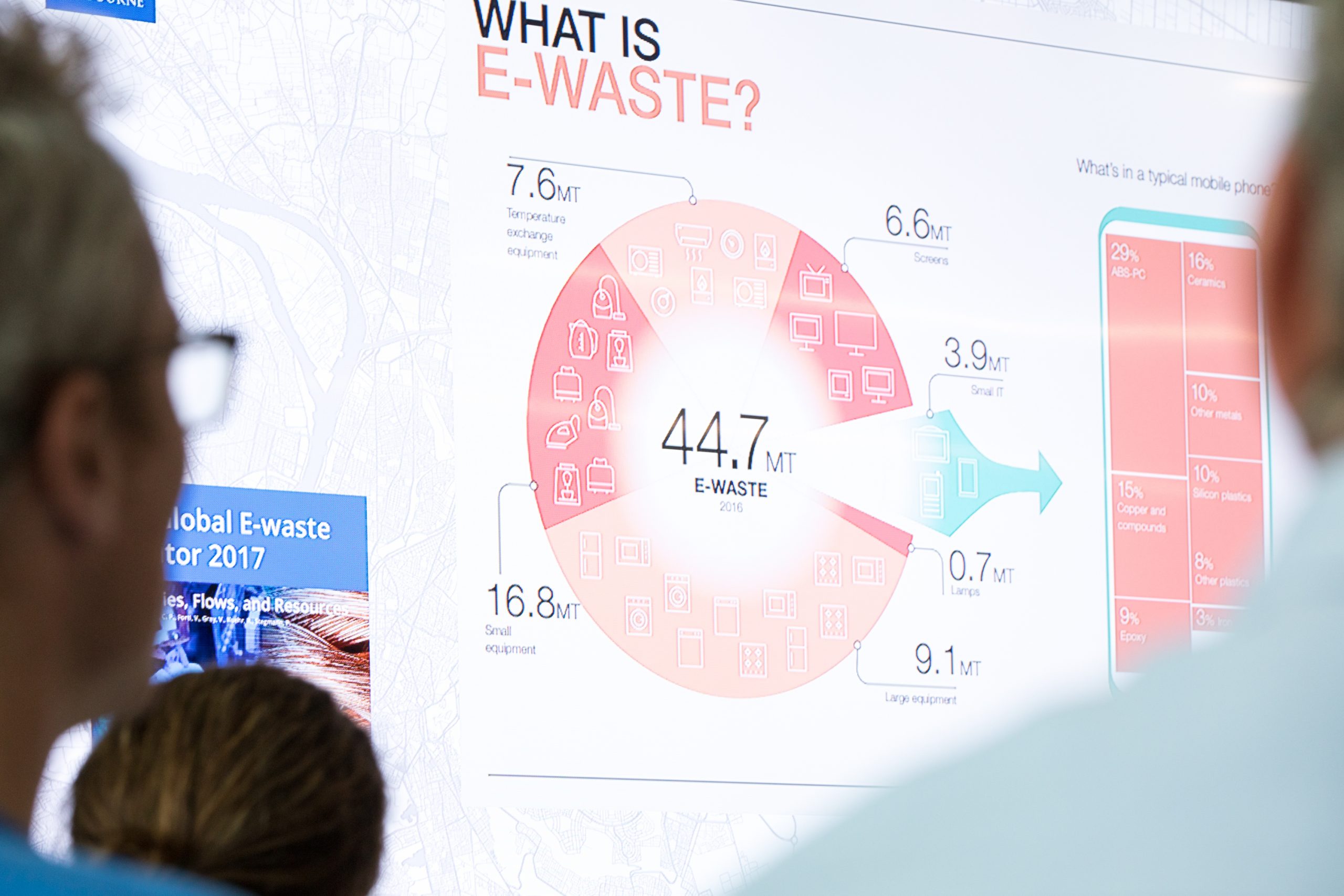

And yet, despite these impressive figures, the global outlook on waste is not comforting: international governance of garbage is fronted by poor data collection, legislation, and concerning international practices. NGOs like Basel Action Network speak of the “High-tech Trashing of Asia” and the global crisis of e-waste management. Global waste flows remain poorly monitored, mostly unaddressed by international instruments and institutions, and largely unregulated besides the more general commercial frameworks on the worldwide mobility of goods and materials. A number of treaties has been put in place to deal with this mass of waste, such as the 1989 Basel Convention on transboundary movements of hazardous waste; yet these tend to deal with special waste, are limited in their applicability, and are confronted with the economic attractiveness of a booming global waste industry.

In reaction to the emerging global ‘crisis of waste’, many are now searching for a local solution. We are witnessing heightened calls for switching as fast as possible to what is known as a ‘circular economy’: catching up with local councils already on board, the Australian government advocated a circular shift in its latest 2018 national waste policy. Championed in the last decade by Ellen MacArthur Foundation, as well as waste advocacy bodies like WRAP (Waste & Resources Action Programme), the concept of circular economy entails moving to an economic system aimed at minimising waste. The idea is to recover and regenerate most resources, rather than disposing of them.

However, switching to a circular system is no easy move. It requires massive shifts in local infrastructure, the difficulty of which was demonstrated by China’s demand for a 0.5% contamination rate in imported waste. Most Australian recycling facilities have for years operated on a less than 5% contamination in export materials threshold and, according to the Waste Management and Resource Recovery Association of Australia (WMRR), upgrading would require a minimum $150 million investment. Yet, as some councils have considered stopgap measures, such as a temporary increases to stockpiling (i.e. temporary dumping) limits, the dangers of short-term solutions have become apparent. Such was the case of the overfilled Coolaroo plant in the north of Melbourne that was the site of a major blaze in July 2017, burning for 11 days with more than 100 homes evacuated.

The challenge at hand is massive. First, the production of our goods is plagued by geographic dispersion: our iPhones are assembled in Shenzhen from components built in Korea, Japan, US and Switzerland, containing materials mined in, amongst others, Indonesia’s Bangka Island. Managing the disposal and reuse of these resources is no easy matter. In 2014, the World Economic Forum (WEF) and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation launched an initiative to scale-up circular thinking across global supply chains. As they acknowledged, we will need to close the international loops of components, sub-components and materials that determine waste and resource flows across continents. This a complicated step change, calling for new business models and global reverse value chains. WEF and MacArthur proposed to do so by thinking circularly on product design and material supply at an international scale.

The interplay of global options and local economics is still critical. In Australia, waste management consultants MRA warned that it is now cheaper to import whole green bottles from Mexico than to make green bottles from recycled glass. Global gateways and flows shift rather than just disappearing, and problems cannot simply be ‘moved’ internationally. The FT has traced the exports of plastic and paper from G7 countries after China’s ban, to reveal a dramatic increase in the flows of waste into southeast Asia. For instance, Western Australia has been shipping almost all its recyclables to Indonesia, Malaysia and Vietnam. However, this shifts the waste crisis elsewhere and is not a long-term solution: Malaysia banned plastic waste importing in October 2018.

Finally, innovation at times works against rather than in favour of circularity. The fast-paced introduction of new materials often outpaces advances in waste management infrastructure, which is simply not ready to manage their disposal. Equally, poor quality and cheaper-to-produce materials account for significant losses. For instance, WRAP and the WEF recently noted how the current low quality of PET, one of the most common materials for plastic bottles, allows bottles to contain no more than 20 to 30% of recycled material.

So, whilst circular economy advocacy has gotten us thinking in the right direction by focusing on reusing, revaluing and localising, the challenge ahead is no small one. In an age of nationalism, walls and ‘us vs them’ thinking, the major risk is that we will understand ‘circular’ as solely domestic. Clearly, what happens overseas directly affects the yellow bin outside our door. We cannot afford to forget that the future of our garbage is not just on the kerbside outside home and the landfills around our cities. It is a global challenge, and if we are to solve it, we will need to work collaboratively, across borders.

A warm thanks to Michele for his introduction to the invisible, but booming, marketplace of garbage! Michele runs Connected Cities Lab, research centre designed to provide information that city leaders need, in an increasingly connected world.

[Main image: One of the typical modified 4×4 trucks used by miners in the local area travels across the expanse of sediment left by mining operations. Photo by Maxim Holland]