Discussing land, treaty and property with Future Method

Future Method Studio work across architecture, installation and speculative projects. Led by architecture practitioners and pedagogues Joel Sherwood-Spring and Genevieve Murray, Future Method is a unique practice in the Australian architecture landscape to put participation and decolonisation at the heart of their agenda. In anticipation of their program at Melbourne Design Week 2019, Jana Perković speaks with Joel and Genevieve.

Jana Perković

Genevieve, my first encounter with your work was reading about how you stepped in to help your neighbour Roslyn renovate her Redfern housing commission home. Was that the beginning of your work on the politics of housing and Aboriginal Australia?

Genevieve Murray

I was labelled the Angel of Redfern by the Sydney Morning Herald: a classic White Saviour story of a girl suddenly struck, through proximity to an early gentrifying wave to hit Redfern, with the vulnerability and precarious nature of life in public housing. The newspapers used Roslyn’s vulnerability for clicks, making her further ashamed of her circumstances whilst all the social credit points were redirected towards me. Yes, Roslyn got to move into a house that didn’t have the floors falling through, new carpet and a fresh lick of paint, but it didn’t trigger the government into allocating their maintenance contracts more effectively. It was my first and necessary lesson in the role I play personally, along with those in positions of privilege, in maintaining and perpetuating the settler colonial project and the ‘creative’ ways in which I was making this pill a bit easier to swallow for myself.

JP Over the years, I have watched your work grow in depth and scale, as you are tackling more issues in a more systemic way. As designers, we are often hands-on people who like to solve problems – but how do we tackle the dispossession of a whole people? It is easy to feel overwhelmed.

Joel Sherwood-Spring

People locate colonisation and dispossession at arrival, at invasion. But this dispossession is ongoing. We are trying to be the saviours in an oppressive system that we are maintaining — this is the reason it feels like something that is impossible to tackle. Unquestionably, there’s no hiding from that.

So, do we stop working? Well, this is the wrong question. If anything, we should all be working harder. It’s what we are working towards, and who we hold ourselves accountable to, that is the question. How are we complicit? Where does our privilege intersect with someone else’s oppression? If you are accountable to the single mother living in public housing in Redfern, then your work must look to address her disadvantage. There are very few existing avenues for this to occur so we must use our ingenuity, rigour and enterprise to tackle that problem in a creative way. We must spend our creative efforts in working out who we need to be speaking to and for and then how!

JP Your work spans design, research, education, writing, and public programming. What do you see as the benefits of each of these processes, as ‘future methods’ for architects and designers?

JSS Architecture performs for a very narrow bandwidth of the population, but it affects the majority, and we have a responsibility to those excluded from this process. So the foundation of our practice is an interest in working with very plural and inclusive methods.

GM And who we include in the process, and how we interrogate the process, affects the outcome. Inclusion, plurality and interrogation are methodologies that span all of our work. The way we use them varies a lot, depending on the space, place or context we are working in. The outcome is not really the point, but it does have some surprising and fruitful benefits.

For example, our most recent commission for the 21st Biennale of Sydney was a conversation through material and form with Redfern. We made set of artefacts: a ‘terrazzo’ table top made from Redfern demolition rubble — used scaffolding mesh, and graffitied construction hoarding from the neighbourhood. These materials were a collection of patterns, words and textures that make up the temporal city, a version of the city left behind by development and renewal. We then hosted a talk in that space with Lorna Munro, Linda Kennedy and Keg De Souza. We had everyone sitting around this big table made out of important buildings that were no longer with us, and because we could talk about where all these things were from, and that it was personal — Joel went to primary school on the Block in Redfern where the rubble came from — there was a completely different realness and impact. The material city is also our material selves, and it is also on and from ‘Country’, as Linda Kennedy reminds us. How we choose to relate to that, on many levels, is the crux of it. The more we get brought into a real relationship to it, the better we are able to respond.

JP Is the architectural profession’s reluctance to engage with questions of our collective belonging in space, and our agency towards space, a reflection of the settler colonial foundation of the Australian society?

GM For most people, engaging with this very crunchy and uncomfortable reality of ongoing dispossession is too hard. We want the safety of the world we know. We don’t want the facade to crumble. Our own fragility and socially constructed desires are the biggest barriers to change on this issue. But at Future Method we believe there are problems at both ends of the engagement spectrum. With those who do engage, particularly in the architectural profession, and particularly at the supposedly woke end of the spectrum, engagement often occurs only at the junctures that don’t make anyone feel too uncomfortable, and are often explicitly or inexplicitly used as social capital.

JSS Yes, and the project of engaging with questions of inclusion and diversity is, at the moment, still a project of extraction from marginalized perspectives. It gives no space for reciprocal respect between Indigenous and non-Indigenous negotiations. We see the present as the project of a problematic past, which it is, yet we are not engaging to make an equitable, diverse and inclusive future that could be better than this one. We are using our current level of pleasure and comfort as the measure.

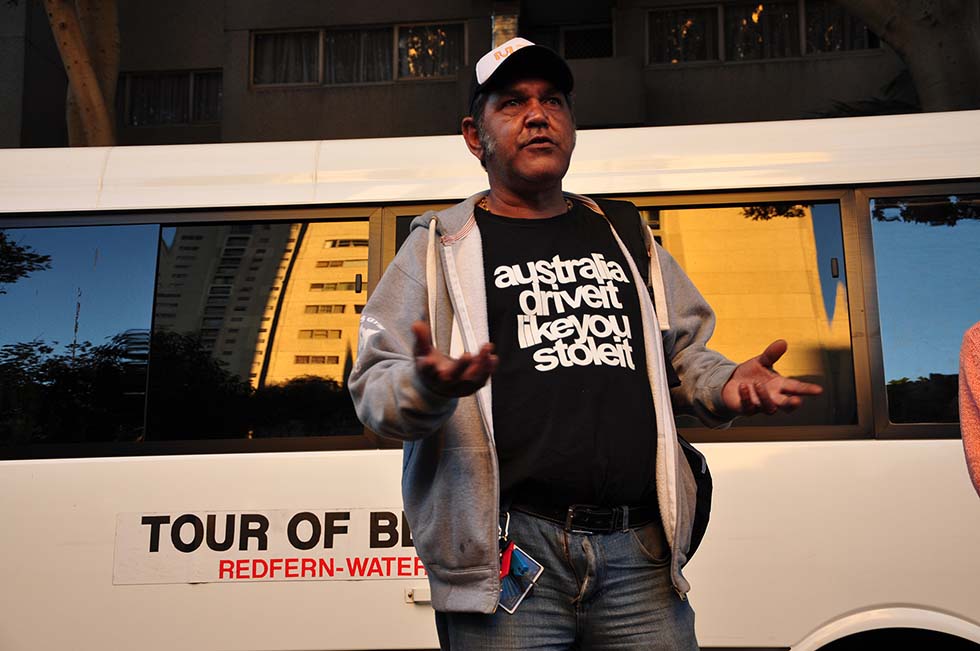

We talk a lot about self-determination, but we should think about what that truly means. Your ability to self-determine relates to your class, your race, your gender, your wealth, your place. I myself sit at an intersection of identifying as Aboriginal and being a spatial practitioner. Though I would like to believe the majority believe in social justice, Indigenous rights, inclusivity and equality of opportunity, we are largely absent from the places and spaces where decisions are made. I say this pointedly: your choice to be absent from spaces where you could leverage your own access to benefit others is of moral and ethical import. Offering real equality is a process of deconstructing your own life determinants and being brave in imaging a future that isn’t based on your own experience of the past, or notions of comfort.

JP You have frequently returned to work with public housing estates in Sydney, and gentrification via their privatization. What is the role of government housing in Australia in delimiting the living conditions (and geographies) of Aboriginal Australians? And can you speak to the historical dimension of the process of land development, e.g. via planned gentrification, as we’re seeing in Redfern-Waterloo now?

GM The NSW government is going through a process of divesting itself of public housing. In Sydney, we are seeing government infrastructure projects like the Sydenham-to-Bankstown metro line drive this process and the ‘uplift’ that is required to support it. This is the biggest change to the delivery of social housing since its inception, carrying big risks for the most vulnerable – particularly those who are survivors of the Stolen Generations, who weather daily racism, police brutality and dispossession and who have complex mental health needs as a result. These higher-needs tenants are less likely to have security of tenure in privately operated community housing. I don’t think it would be far off the mark to call it social cleansing. So this process, and the gentrification that is the driver of property sales in the area, marks a new wave of displacement; of moving Aboriginal communities to the land that doesn’t have value, to capitalise on land sales.

The story of Waterloo, at the southern end of Redfern, is in its name. It was part of a system of small creeks and waterholes that stretched all the way down to Botany Bay. Aboriginal people were pushed to the fringes of the city (which Redfern was for some time), onto the land which couldn’t be farmed or used for settlement. Now, because of its relative proximity to growth centres and the CBD, there is a new wave of dispossession, a process that has been underway since the 1970s. You can see that nothing has changed in the methodology in 240 years. No number of community consultation sessions or Indigenous advisory groups will change this; they are all just sugar-coating the pill.

JP As professions, architecture and town planning are deeply involved in spatial processes of colonialization, settlement, segregation, removal of people from land – and yet this is not something often discussed, or learnt about in architecture school. What are your thoughts on the necessary pedagogy of decolonialization?

GM Decolonisation operates in two directions, and means two very different things for a white settler colonizer, and for someone who is colonised. This is the most important distinction to make. Future Method includes both a white settler/coloniser (me), and colonised (Joel). So we each work in different directions.

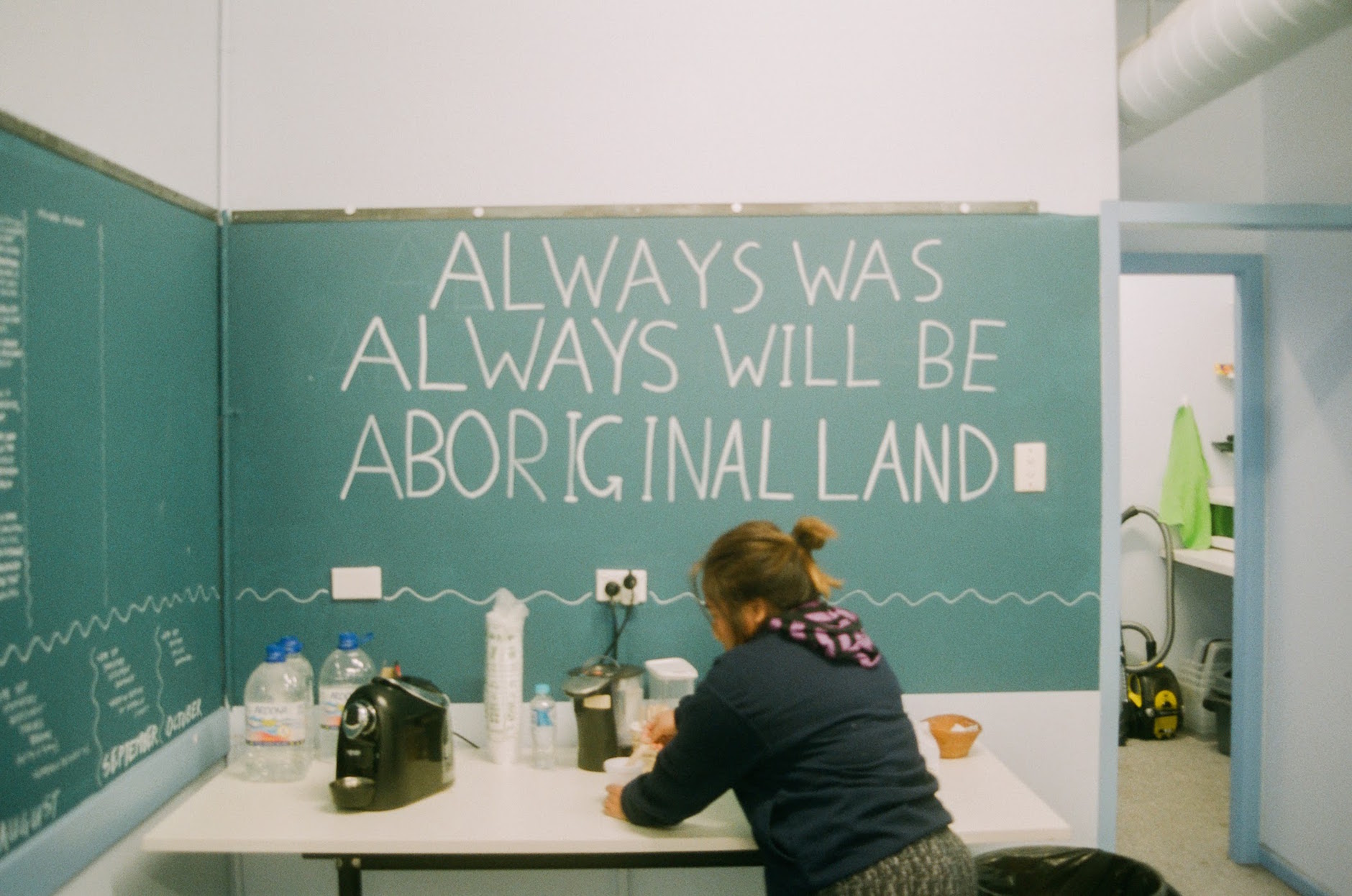

One way architecture schools can address this very problematic denial (of a very well-documented condition) is to forget the ‘global’. We must understand that we exist in place. That this place is on ‘Country’, that is stolen land, and that we have a role as planning and architectural professionals in the ongoing denial of sovereignty and dispossession. That’s what we choose to preference in our curricula at UTS (where we both teach).

If the people deciding on our curriculum were those impacted the most, then we would begin to see a meaningful transformation in the profession and in our pedagogy. But I think, and this comes from experience, that anything or anyone that is brought into an institution, in the contemporary Australian context, undergoes a process of colonisation. Our institutions are the way in which the colonial project is maintained, not dismantled. There can be no such thing as decolonizing in this context.

JP Who are the people whose work in this realm you particularly admire?

GM Linda Kennedy is the strongest and most inspiring voice of our time.

Thank you to Joel and Genevieve for sharing their thoughts with us. As part of Melbourne Design Week, you can attend their three round tables on decolonising architecture, Future Acts, which will be held at Testing Grounds: Designing Oppression on Friday 22 March, Housing, Gentrification and Aesthetics on Saturday 23 March, and Land, Treaty and Property on Sunday 24 March. Free entry, and bookings are not required.