Come Together

Urban planners and designers are working to curb Perth’s sprawling ways, to create a more connected, productive and cost-efficient city. Logic, facts and statistics tell us that there are considerable environmental and economic risks if we don’t.

To meet this challenge, industry is developing denser housing types and governments are formulating planning policies and processes to further encourage this type of housing. However, the outcomes are variable. The discussion around this transition plays out in most local newspapers, where the rationale for infill meets local outrage and pushback. Communities and elected members can be apprehensive at best, and professionals are frustrated by the sluggishness of the move away from Perth’s traditional suburban culture.

The challenge of achieving community buy-in is a complex one, so efforts to communicate and engage when working through new plans for Perth’s established areas must be authentic and relevant. There are several ideas that towns and cities in Western Australia can explore in order to achieve better relationships between professionals and citizens.

One idea is to take consultation out of the town hall and into local areas, so everyone can engage and be heard. Jane’s Walks, named after the late urban activist Jane Jacobs, are free, locally led walking tours in Perth and hundreds of cities around the world. They work on a simple concept: get people out of their houses to learn about and contribute to the shared story of that place. When you turn up to a walk you notice the hierarchies of a formal workshop are virtually non-existent – there’s no government official talking at you about your own neighbourhood.

Walking is said to help boost creativity. On Jane’s Walks, walk leaders take locals through backyard veggie patches and past heritage gems, to modern apartments and the local train station, and at any time citizens can add their insights and suggest ways to improve the place. They may offer thoughts on pedestrian improvements, public art or housing opportunities.

This ‘walkshop’ concept can be broadened to allow locals to become involved in helping to solve problems – like ‘maintaining neighbourhood character while achieving infill’ or ‘ageing in place’ – and weigh up difficult, often conflicting, choices. Ideas are usually captured through journalling, sketching and photography. This year the Perth walks ran in eight local areas and attracted over 300 locals, who offered rich feedback based on personal experiences.

Getting locals out and about can be coupled with other communication tools, like visual policy documents that can help translate planning language into terms the layperson can understand and which, importantly, help them to contribute. If planning isn’t accessible, we don’t hear from those who live on the margins of our communities. As a result, the young, old, migrant households, students and transient populations are usually underrepresented.

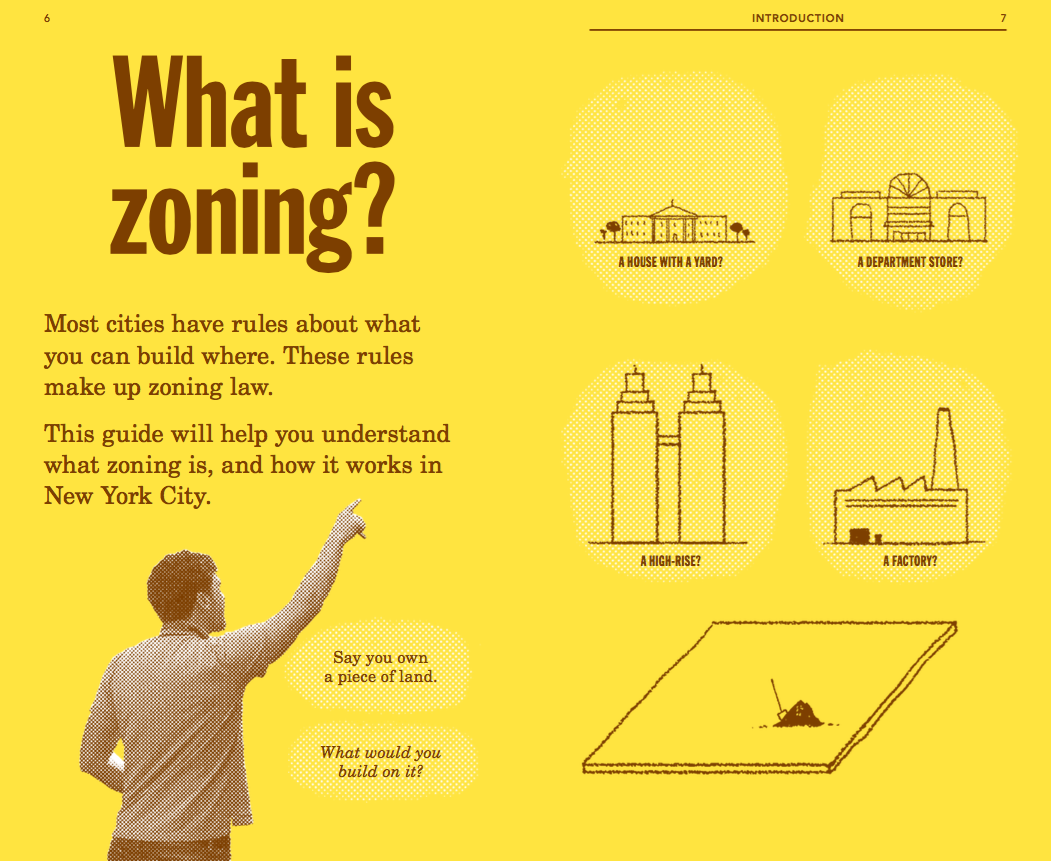

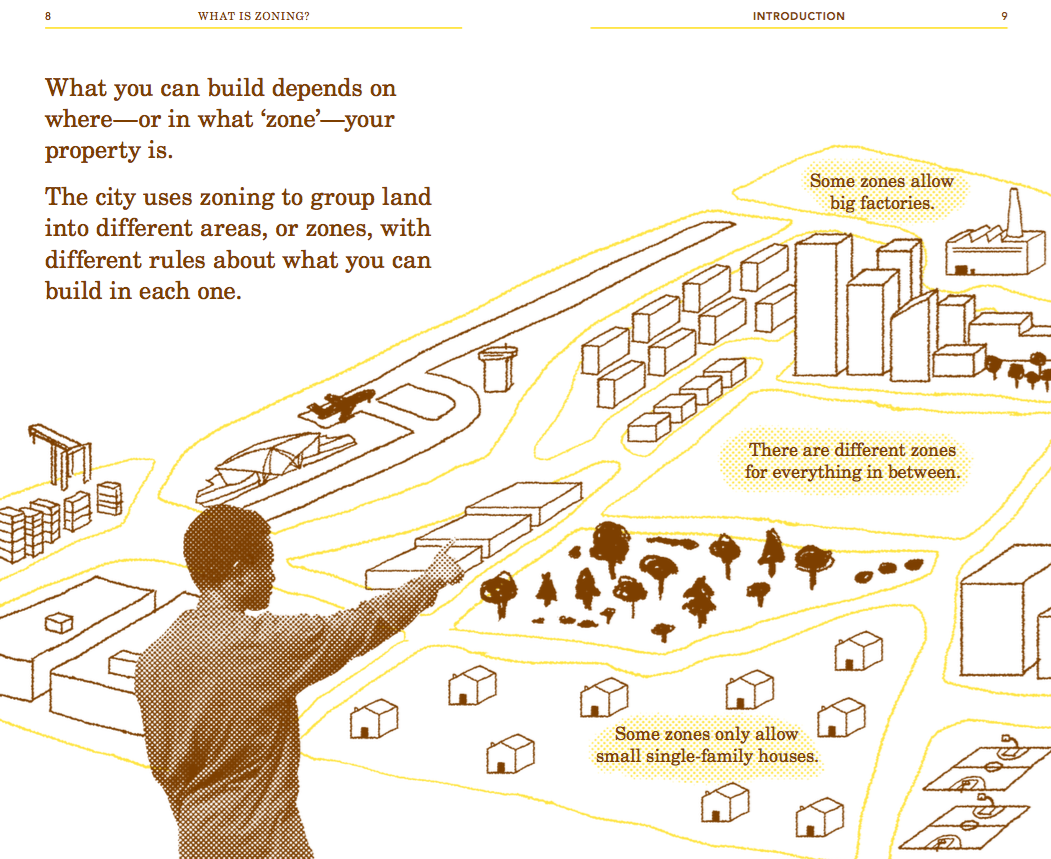

The Center for Urban Pedagogy in Brooklyn, USA, is finding new ways to reach out to such groups through its Making Policy Public project. The idea is to explore and explain public policy through well-designed foldout posters, rather than relying on text. The Center pairs advocacy groups and governments (usually the policy’s owners) with graphic designers through a competitive process that targets communities that will benefit from clear communication.

Successful past examples include ‘What is Zoning?’ and ‘What is Affordable Housing?’ – two visual policies that come with resource kits that can act as standalone guides or be used in community consultation and schools.

The Center also developed the collateral ‘How Can I Improve My Park?’, an initiative to show New Yorkers how to turn common complaints into proactive campaigns for public space upgrades and take greater ownership of maintenance issues. ‘Why is Chinatown Getting So Expensive?’, another communication piece, explained the city’s Rent Stabilization Law through iconography and multilingual translation.

‘Localism’, a term that refers to communities showing interest in the way their neighbourhoods develop, has helped to improve community buy-in to local planning. In the UK citizens are now able to lead the preparation of Neighbourhood Plans (in WA there are similar plans called Structure Plans) under the UK Localism Act. Citizen groups, using local government technical resources and funding, can draw up their own plan provided it’s in line with national planning policies and the strategic vision set by local government. One of the main requirements is that the plan must accept (or exceed) pre-set housing density targets. Once a plan is produced and a simple majority reached through referendum, the local authority will bring the plan into force.

The UK government recently declared that over the last five years 200 Neighbourhood Plans have been prepared and are legally in force. Supporters suggest the plans successfully devolve power to everyday citizens, allowing them to have genuine opportunities to demonstrate innovation, influence the places that they live in and share responsibility for housing targets. Many developers back the concept as it brings about difficult conversations about housing densities that would otherwise have waited until their proposal was being assessed.

However, there are critics. Some commentators suggest the plans have put the brakes on housing projects in some areas, are difficult to apply in large cities where greater strategic planning is required, and act as a cover for meaningful community influence without stronger devolution of funding and taxation control to match the potential of the Localism Act.

When professionals dedicate the time to properly engage the people they are planning for it can close the communication gap and transform potential protesters into true advocates of change. Citizens who understand the inevitable trade-offs involved with infill developments help reduce risks and add valuable insights that contribute to building a better city.

*

This is the third in a series of articles we’re sharing from Future West (Australian Urbanism) – this time from the second and most recent issue. Future West is a print publication produced by the University of Western Australia’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts. Future West looks towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point.

Original image: In 2016, Jane’s Walk Perth held three days of walks: in Bayswater, Daglish and Perth’s CBD. The walks explored the themes of heritage, art, sustainability and urban design. Photo by Nic Temov.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Nic Temov is an urban planner and co-organiser of Jane’s Walk, Perth.