Using play to imagine future cities from queer utopias to communities on Minecraft

The Tower of Babel, Metropolis, Alphaville, AI-generated urban environments – visions of future cities have forever captivated the public imagination. Yet opportunities for citizens to engage their own imagination towards improving their cities have historically been limited within the prevailing ‘top-down versus bottom-up’ planning paradigm. As calls for approaches beyond the binary increase, the act of play has emerged as an impactful co-design tool not only for catalysing citizens’ imagination but also for facilitating its realisation.

Whether using building blocks, found objects or digital environments, play serves a serious purpose. It can offer a safe space for collective critique, solidarity and healing, particularly for people who have felt oppressed, marginalised or excluded by traditional city planning. From California to Narrm via Central Java, Assemble Papers hears from three change agents tapping into play’s potential.

Reframing City Design Around Memory and Emotion

In contrast to the rationalist tradition underpinning city planning in the United States – ‘highway, housing, infrastructure’ – Southern California-based urban designers James Rojas of Place It! and John Kamp of Prarieform centre their respective and often collaborative practices on feelings. “We like to talk about planning as something that everyone can do, down to planting a tree in front of your apartment building,” says Kamp.

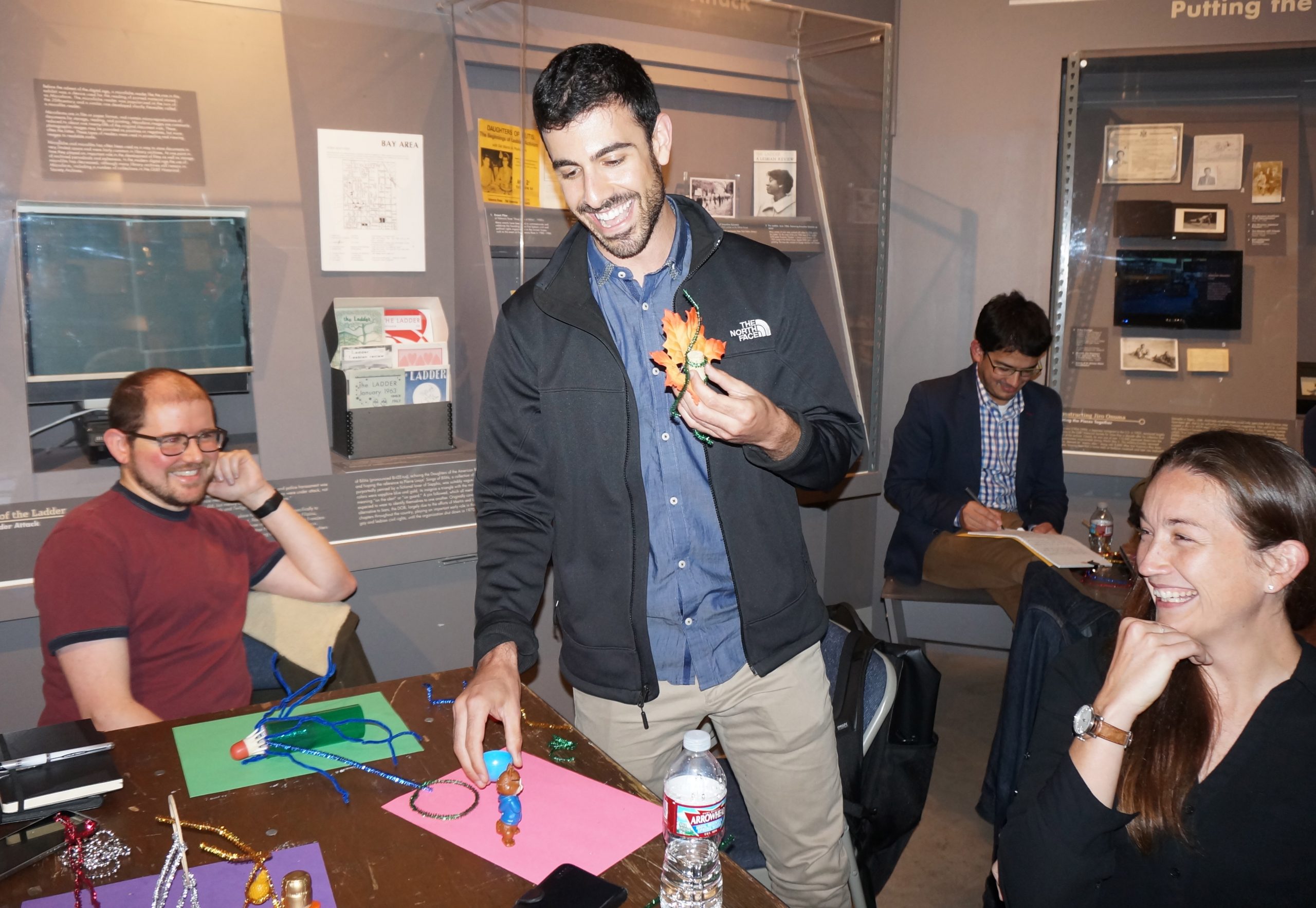

“We try to show people that planning is also your emotions, and how you perceive and think about places,” Rojas adds. “The city in your head is just as real as the city itself.” However, he acknowledges: “For a lot of people, it’s hard to articulate how those places feel.” Accordingly, Rojas and Kamp use creative, hands-on methods in their community engagement work, facilitating new approaches between citizens and planners during urban-planning outreach meetings.

“If you ask people in the US what they want, they’ll often say, ‘More parking, less traffic, no density,’” Rojas continues.

“But when you have them there, [building] with their hands, it becomes about what their body and their mind needs: ‘My body needs warmth, comfort, shade, quiet. And I need love and attention.’”

The interactive model-building workshop Rojas and Kamp describe in their Dream Play Build manual begins by gently nudging participants’ mindsets towards the point where they can “articulate how a place feels, how they want places to feel, and also how places did feel when they were growing up.” To do so, they prompt participants to turn their minds back to childhood.

“Often when people come to these meetings, they’re angry, they’re hungry,” says Rojas. “When we have them build their favourite childhood memory, all that stuff leaves them. Now, they’re happy and in the right space to build for the future. I’ve done these workshops 1,500 times, maybe with 10,000-plus people, and no-one’s ever once built their house and their car, their private space.”

Much of Rojas and Kamp’s work sees them engage with historically marginalised communities for whom public spaces can be loaded with hardships and traumatic memories. Whether inviting people with disabilities to design their ideal light rail station in Phoenix or workshopping queer utopias with LGBTQIA+ folks, they’ve found that a light-hearted approach is the most effective therapy.

“The elements of playfulness, colour, silliness, whimsy don’t diminish the fact that you’re working around a topic that’s serious,” says Rojas. “It’s the act of building and working with your hands that’s giving you that sense of lightness – that is the therapeutic process. That’s a big part of our work – understanding that there are ways of making people feel good, giving them a sense of healing, and a sense of possibility.”

Gaming as a Channel for LGBTQIA+ Storytelling

How can digital world-building foster open possibilities for those for whom urban design has historically underserved? Investigating this question through the lens of queer gaming is Narrm-based researcher and designer Dr Xavier Ho. Through lectures, writing, art and design, Dr Ho both deconstructs and contributes to building safe digital spaces for queer communities to come together, connect and explore new modes of expression – or simply spend time in an environment of self-determination.

“Games are leisure spaces powered by imagination,” Dr Ho says. “For queer folks like myself, games are safe spaces we create for ourselves – and to be ourselves in those spaces with friends with whom we have a mutual understanding.” Collectively creating within a digital environment free of constraints offers a testing ground for navigating physical spaces and the social dynamics that bring them to life.

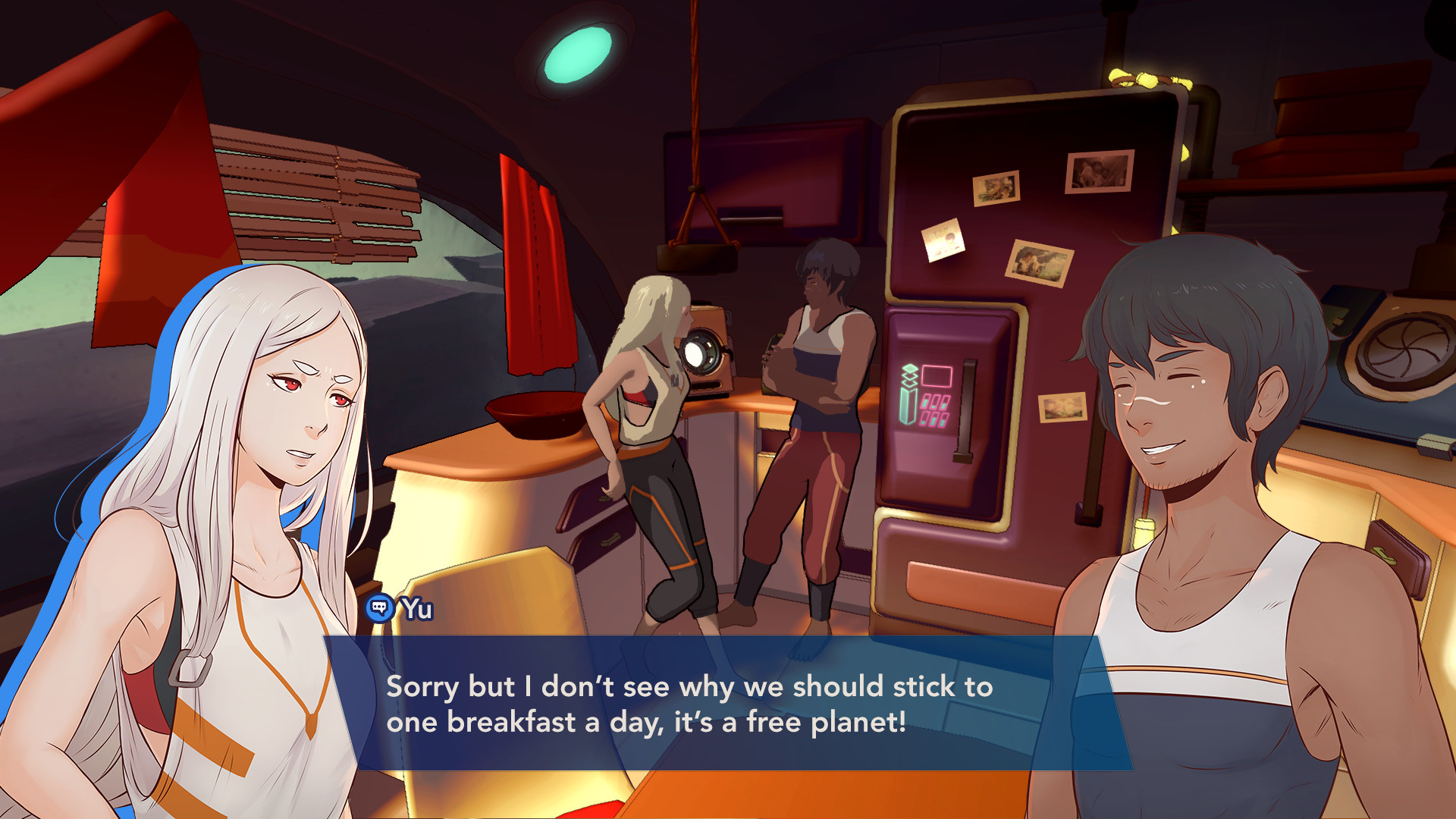

The Game Bakers’ 2020 role-playing video game Haven exemplifies this. Two players can adopt the persona of a gay (or straight) couple “about to discover an ancient secret of their own space-faring civilisation,” as Dr Ho says. The game takes place in a spaceship converted into a home, setting the scene for quality time with gamers’ chosen partners.

“This allows you to imagine what it would feel like to live together in an imagined world. That’s powerful for people who want to ‘try it out’ before making the move.”

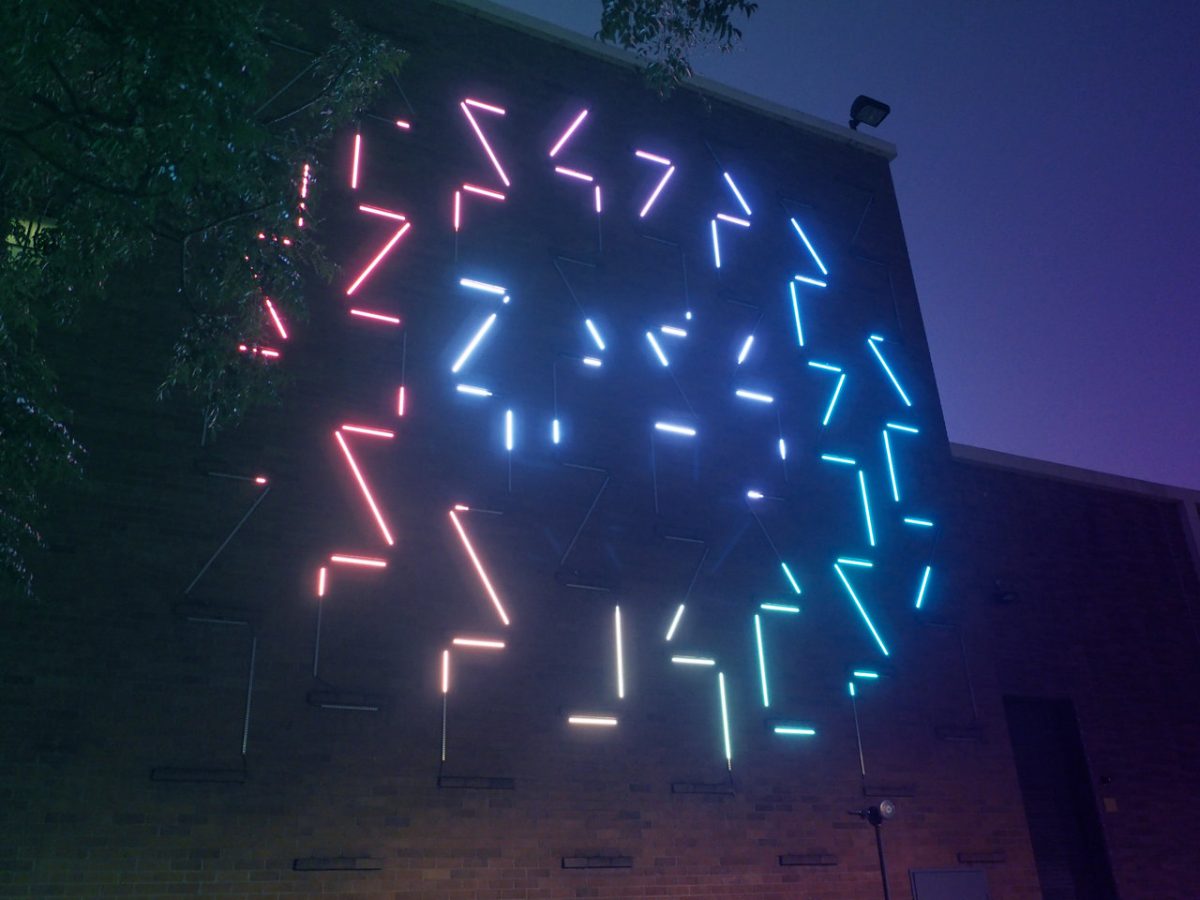

Reflecting how city planners can better create safe and inclusive environments for LGBTQIA+ communities, Dr Ho emphasises the importance of intersectionality. “There’s no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to city planning and development. It’s about providing multiple ways for access to common needs: comfort, commute, social gatherings.” That said, he notes Sydney WorldPride’s Rainbow City project as a positive example of leveraging art towards creating inclusive urban spaces.

As part of the 2023 festival, 45 rainbow murals were installed around town to celebrate 45 years since the late gay rights activist Gilbert Baker created the rainbow flag. Noting that town halls, street corners, parks and shops across Sydney have since kept their murals on display, Dr Ho praises the impact of this urban intervention on urban inclusivity: “It reminds us that queerness is something to be proud of, to have the confidence to be ourselves, and that we are welcome.”

For Dr Ho, it comes back to storytelling – who gets to write their own narrative and see it reflected in the world around them. “Games as imagined spaces are also social spaces for storytelling. That includes all kinds of stories – above all, stories about how we connect our senses of self to the digital world. Urban design, too, needs to facilitate those social meanings,” he says. “We need to design cities that are welcoming to everyone in ways that encourage the best out of every community, empowering them to develop their own spaces. Not just the visible public bit, but also the invisible semi-private and private parts of our everyday life, too.”

Manifesting a Community Park on Minecraft

Across the compact, low-slung city of Surakarta – also known as Solo – in Central Java, Indonesia, a small NGO is having an outsized impact on supporting communities to design their own spaces. Ahmad Rifai, co-founder and executive director of Kota Kita, describes the circumstance his organisation is working to change: “In most Indonesian cities, citizens are not yet involved meaningfully in the decision-making processes of urban plans and initiatives.”

“While there are formal mechanisms such as musrenbang [participatory planning and budgeting], the involvement of citizens in these forums has often been a formality,” Rifai says. “Where consultation does occur, it is usually focused on providing feedback after projects are completed. Rarely are citizens asked whether projects are needed or how they should be designed. As a result, urban spaces and policies may not adequately address the needs and aspirations of communities, particularly those marginalised and vulnerable.”

To bridge the participation gap, Kota Kita draws on a range of tools and methodologies united by a common aim: “to create a space for all citizens, regardless of age, gender, abilities and other characteristics, to voice their aspirations,” as Rizqa Hidayani, program manager for Kota Kita’s urban resilience initiatives, puts it. In the 2023 initiative Rivers as Inclusive Common Spaces, Kota Kita collaborated on catalysing the co-design of new communal space for residents of Rusunawa Mangkubumen, a public housing community in Solo’s Mangkubumen neighbourhood, near the Solo River.

Following a persona-based exercise to identify the needs of the community’s most vulnerable members, Kota Kita engaged Block by Block Foundation to create a model of the site on Minecraft, in which residents could then build the space for themselves.

“By incorporating Minecraft, the workshops fostered active participation, especially among children, who could contribute ideas in a fun and engaging manner.”

A virtual reality: the design and creation Taman Rukun Mangkubumen in Surakarta came about by engaging local community members with the online gaming platform of Minecraft. Image: Kota Kita.

It wasn’t long till residents were able to experience the manifestation of their ideas, in the form of Taman Rukun Mangkubumen, a public park providing over 300 residents in 80 households with a space to gather and play.

As with other Kota Kita initiatives, the project has had ripple effects beyond its immediate beneficiaries. “[Our] pilot projects have served as entry points for our advocacy efforts with local government officials,” notes Rifai. “Through these inclusive public spaces, we’ve shown government officials the value and importance of citizen participation in the development of spaces – and even inspired a few local government officials to incorporate the approach [in] their governance practices or even policies.”