Home is where the land is

Piece by piece, the land was stolen. As Wilson Williams — a band council member of the Indigenous Squamish Nation in British Columbia, Canada — tells it, the creeping land grab by non-Indigenous settlers reached official status in 1877, when Canada’s federal government confined his ancestors to living on a 34-hectare reserve. Up until that time, they had flourished in and around the ancient village of Sen̓áḵw, a seaside trading hub at the mouth of False Creek in what is today Vancouver.

“Sen̓áḵw was a place of abundance,” Williams says. “People hunted elk, beaver, duck and deer; they fished for salmon. And they had access to lumber,” he explains, referring to the cedars used to build longhouses and make dug-out canoes. But the colonizers even started taking chunks of the reserve land (making meaningless the definition of “reserve”) to make way for railroad extensions and industrial expansion, all of which accelerated after the Great Fire of Vancouver in 1886. The final death knell to what remained of Sen̓áḵw came in 1913, when the provincial government of British Columbia evicted the Squamish people from the reserve and burned down their homes. “Police gave them two days’ notice to leave,” says Williams, his great-grandfather being one of the dispossessed. “Those who refused to leave because they didn’t want to lose the connection to their land were loaded onto a barge and set adrift.”

For Indigenous people, for whom connection to land means connection to self, expulsion from one’s ancestral territory is tantamount to being made homeless — “home” signifying much more than the dwellings, be they temporary or permanent, erected on that land. In Indigenous ontologies, home is also the land that supports those structures and feeds the life and community, the stories and ceremonies that take shape in and around them. This contrasts with the Western notion of home, which tends to mean “housing,” limiting the potential for wellbeing to the shelter offered by a house and the value wrested from it when treated as a commodity.

The fate forced upon the Squamish people — the twin dispossession of land and destruction of homes — is a history repeated in many parts of the world.

In the countries that are today referred to as Canada, Australia and New Zealand, as British colonizers evicted Indigenous peoples from their lands, they also placed a chokehold on Indigenous self-determination. They outlawed governance systems and ceremonies that had thrived for millennia and snuffed out economies, knowledges and livelihoods grounded in communal wellbeing and kinship with the land. In so doing, they also erased the physical spaces and dwellings people inhabited, from First Nations longhouses and Māori marae and papakāinga to the multitudes of housing typologies designed by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island peoples in so-called Australia to respond to differences in climate, culture and material availability.

While home and housing are not necessarily the same, one can determine or influence the other, with consequences for health outcomes. When people are robbed of the title to or ownership of their land, they no longer control what happens on it, including policies to do with the construction of and access to housing. As the Crown in Australia, New Zealand and Canada deported Indigenous peoples from their lands of plenty into poverty on government-determined reserves, it forced them into shoddily built and culturally inappropriate houses meant merely to provide a roof but not to nourish community, good health and wellbeing. The colonial policies created housing insecurity, overcrowding and homelessness.

These impacts of colonialism on Indigenous housing reverberates today. According to Canada’s 2021 census, people in First Nations communities are four times more likely to live in crowded conditions and six times more likely to live in houses in poor repair than non-Indigenous people; the Inuit are 40 percent more likely than the non-Indigenous population to be housing insecure. In Australia, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, in a report under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework, shows similar statistics for Indigenous housing, with First Nations people facing discrimination in accessing quality housing and being less likely than non-Indigenous Australians to have the financial means to buy or rent secure homes in good repair. What’s more, the rate of First Nations people being unhoused is almost 10 times higher than for the non-Indigenous population. The Indigenous housing crises in Canada and Australia are mirrored in Aotearoa New Zealand, where Māori are five times more likely than non-Indigenous people to be unhoused and where the homeownership rate for Māori is only 28 percent compared with 57 percent for non-Māori, per the government’s 2023 report “An evaluation of whānau experiences of living in contracted emergency housing.”

Today, however, Indigenous peoples in Canada, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand are rewriting that narrative by increasingly taking control of what housing can and should look like and building quality homes that fit their specific needs at affordable prices. And increasingly, this happens on land returned to Indigenous peoples as part of land claims, as in Canada, or as part of the Crown making amends for having broken treaties it signed with Indigenous nations, as with the breaches to Te Tiriti o Waitangi in Aotearoa New Zealand. Take the Tauhara North No. 2 Trust, based in Rotorua on the north end of Te Ika-a-Māui, or the North Island. The trust has as its core goals to provide services within the scopes of health and education for its iwi, or tribe. “But you can’t have health if you don’t have quality housing,” says Wikitoria Hepi-Te Huia. So the trust also runs a housing division, Tauhara North Kaitiaki Whenua, of which Hepi-Te Huia is the director. The housing arm is in the process of building homes for its iwi, an endeavour that reflects the broader spirit of the National Māori Housing Strategy, a Māori-Crown partnership that aims to uphold the right to secure, quality housing as a cornerstone of building a better future for all Māori.

A key motto and cultural aspect of the Māori is Toitū te whenua (Hold fast to the land), reflecting the Indigenous idea of home as being more than just the dwelling one occupies. When the British colonizers stole the land — the whenua — of the Māori, they inflicted on them a similarly violent uprooting as that suffered by the Squamish people in British Columbia. The Māori, like their brethren across the Pacific Ocean, were set adrift in a system foreign to them and deaf to their ways of living. And so, for Hepi-Te Huia, access to housing is a social justice issue that needs to be addressed in a holistic way. “For us,” she says, referring to the trust and to her iwi, “it’s not about housing; it’s about building homes.” At the trust’s brand-new Hamlin Road development in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland — a 30-home complex inaugurated on April 6 with much optimism for the future — families have now moved into bright apartments of varying sizes to suit their needs. “People need quality homes where they can feel safe and secure, not at risk of having to move again and again,” says Hepi-Te Huia, reflecting a common occurrence for many marginalized Māori living in substandard government-run social housing.

“Our goal is to build homes for the long term, where people can live for many years, even their whole lives.”

The model, and the Hamlin Road homes, was realized with grant funding from the Crown and income from an energy partnership the trust has in a geothermal project. It offers subsidized housing, at 80 percent of market rent, but residents able to pay market rent can do so and funnel the 20 percent on top of the subsidized rent into savings they can use to eventually purchase their homes. The long-term thinking opens avenues for flexibility that wouldn’t be possible without the trust exercising control over the housing it’s providing.

For the Squamish people, it was long-term thinking that would put them at the vanguard of housing innovation in Canada. After decades of legal wrangling to take back their land — work that was partly spearheaded by Williams’s great-grandfather, Andy Paull — the Squamish Nation in 2002 won a British Columbia court decision that ordered the railway company to give back a 4.2-hectare parcel in downtown Vancouver, where the village of Sen̓áḵw had once been located. That sliver of ancestral land is now being converted into a mega housing project, or, as Williams puts it, “the largest Indigenous land development in Canadian history.” Named Sen̓áḵw and carried out through a 50-50 partnership with Vancouver-based real-estate developer West Bank, the project will feature 6,000-plus rental apartments, including 1,200 affordable units and 250 “deeply affordable” apartments for Squamish Nation members. “It’s reconciliation in action,” says Wilson, adding that the high-rises will add sorely needed rentals for the general population in a city that suffers from a chronic housing shortage. But the rentals model is foremost a deliberate strategy to ensure long-term income. “Sen̓áḵw represents sustainable economic development for our people and future generations,” Wilson says.

Designed to be environmentally sustainable, it will be the largest net-zero community in Canada, showing the world how the Squamish people are stewards of their homeland.

While the Squamish Nation has been able to negotiate a modern land claim that has given it the autonomy to scale up its housing model, and the Tauhara North No. 2 Trust has been able to build homes for its iwi on Māori land, the concept of “land back” is not something that Indigenous people in Australia can take for granted. In fact, the government of Australia, and the British Crown before it, has never entered into a treaty with First Nations people that gives them land rights. As a result, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island people have little to no control over land, making it difficult to implement a social-justice framework for Indigenous housing. As Kieran Wong — co-founder and partner at the Fulcrum Agency, a Fremantle-based (and non-Indigenous) architecture firm that works almost exclusively with First Nations in rural and remote areas — says, this lack of land rights needs to be completely overhauled. “My home is on land I own, that I have title to. It’s called green title, and with it I can do whatever I want or say no to whatever I don’t want on my land, like a cattle ranch. But Native title in Australia only gives Indigenous people the right to be there, but not to make decisions as to what happens on the land,” Wong explains. So if a mining company wants to start exploiting Indigenous land, the First Nation that has lived there for millennia has no legal right to oppose it as they don’t have title.

Add to the land rights injustice the colonial-inflicted intersection of trauma and poverty and a paternalistic housing policy, and you’ve got a system that has ostensibly tried to “help” by offering funding for housing, and then repeatedly defunding and killing those programs. “A major challenge with funding for Indigenous housing initiatives in Australia is that governments fund bedrooms to deal with overcrowding as opposed to funding housing as a whole,” Wong says.

“But for First Nations people, overcrowding is not what drives the conversation; what matters to them is maintaining kinship ties, movement between communities, mobility.”

Here, as in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland and Vancouver, the Indigenous notion of home goes far beyond the narrow, Western concept of housing. “People tend to think about houses, but the bigger issues are land, infrastructure, affordability and durability,” Wong says.

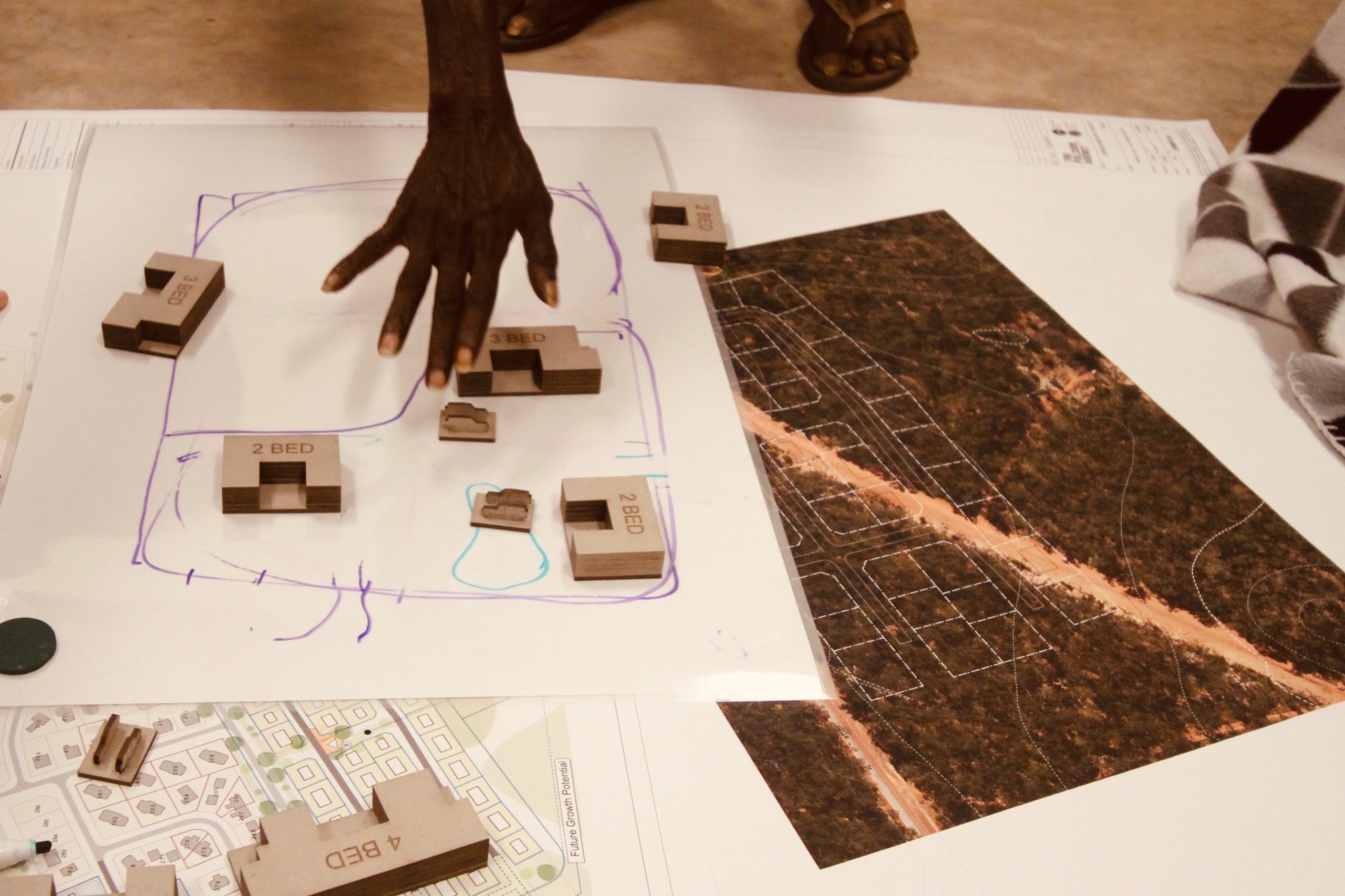

On a more micro level, but with major importance for the First Nations looking to improve housing for their members, Wong says that while he can’t change building codes or housing policies, his firm can — and is — working with Indigenous communities to create culturally appropriate homes that are built to last. This starts even before entering a client relationship. “We don’t go after First Nations clients, because it’s not up to us to determine their needs or dictate what they should want. We only enter a client relationship after the client has come to us. And that’s when our job is to listen and learn,” says Wong. This puts the First Nation in the driver’s seat from the outset, whether the client is looking for Fulcrum to design homes, provide support on funding and grant applications or envision infrastructure upgrades. Despite the numerous roadblocks slowing down progress in First Nations housing in Australia, several communities have successfully implemented housing initiatives that serve their needs — including the Anindilyakwa Housing Aboriginal Corporation on Groote Eylandt, an island off the northeast coast of Northern Territory, which represents the first time an Indigenous community in Australia decided how it wanted its homes to be built.

As examples in Canada, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand show, when Indigenous peoples are enabled to control their economic, social, political and cultural futures — and when architects listen to their needs when it comes to designing housing — they create socially and culturally sensitive homes that respond to the needs of their communities and sometimes even of the broader society. Indigenous housing must be controlled by Indigenous people to address the injustices and inequities that linger from colonial-imposed marginalization. But for full control of housing, Indigenous people need to gain control of their homelands. In the meantime, they are rebuilding their cultures, their economies, their homes. Brick by brick, log by log, they are constructing their own destinies. Only then can they be secure in the knowledge that they will not be set adrift into the unknown.

Traditional groundbreaking celebrations at the future site of Sen̓áḵw: a 6,000-plus rental housing precinct on Squamish lands, for Squamish Nations members. Video: Sen̓áḵw