Creative revitalisation of business precincts built for bygone industry

References

Post-industrial enclaves have long provided fertile grounds for creativity and innovation. Consider the depression era of 1960s lower east New York that spawned cultural icons like Andy Warhol and institutions like the Hotel Chelsea.1 Music subcultures like Chicago house or Detroit techno thrived in abandoned warehouses, as did the European rave scene from Manchester to Berlin. The shelled-out factory walls of Crittall-style windows and expansive floor spaces open to the imagination – one industry’s wasteland becomes someone else’s playground.

Historically, the lure of cheap, spacious accommodation has drawn artists and their communities to dilapidated inner-city pockets, organically sparking their revival and inspiring fresh approaches to urban revitalisation. The ascent of the creative class in post-industrial city precincts is what theorist Richard Florida sees as an essential ingredient of modern-day urban economics and regeneration.2 From city-wide revival plans to arts-led renewal projects, creative communities can breathe life back into the bones of old business and reignite these engine rooms with new ideas and legacies.

Crafting creative commons at Distillery District, Canada

A former liquor manufacturing hub spanning 13 acres and 44 heritage buildings, Toronto’s Distillery District now bubbles away with a new creative spirit. As a redevelopment that prioritised adaptive reuse and arts-led regeneration, this pedestrian-only, cobble-stoned precinct has become a must-visit city attraction filled with creator markets, local start-ups, and entrepreneurial pursuits.

Retain over restore: where possible, the decision was made to incorporate heritage ideals into an overall design strategy for a reimagined Distillery District which reopened in 2003. Image: Julio Cesar Mercado.

A logistical juggle for practitioners, over 100 building permits were awaiting approval during the height of the planning phase. In pivoting from one industry use to another, community-led consultation was key to informing accessible, inviting spaces so they could be activated in new ways; “to make an invitation to the arts community for their involvement was essential to ensure that the district was inclusive of their initiatives,” explains Michael McClelland, Principal Architect from ERA Architects.

With no chains or big brands allowed, tenancies are reserved for local creatives who can respond to and make their spaces their own; “Artists are urban pioneers, and they tend to drag their friends along,” lauds Michael.

“They were the first to move into the older buildings and more than 50,000 square feet of space was rented to them at below-market long-term rates.”

McClelland speaks to ERA Architect’s commemorative approach: where possible, patinas and worn industrial edges were purposefully kept and worked into the reimagined quarters, “creating a place to be experienced as a current and living entity and part of our contemporary urban environment.”

As regeneration tends to spark more regeneration, there are opportunities for others to move in next door. Canary Landing, a multi-building housing development to the east of Distillery District, represents one of the country’s largest purpose-built rental communities. Of 2300 rental homes built, 30 percent will be dedicated to affordable housing and another 25 percent dedicated to barrier-free homes.3

Trendsetting change in Seongsu-dong, South Korea

Once the footwear-making hub of 1970s South Korea, Seongsu-dong now draws shoppers from behind their online carts and into a suburb that founded ‘newtro’ culture – a style that is part-contemporary, part-1990s nostalgia. A 2010s resurgence of activity and ingenuity has seen this warren of warehouses become home to South Korea’s next generation of creatives and future thinkers.

From tech start-ups to creative co-working spaces, up-and-coming atelier studios and Salt Bread bakeries, new ventures are finding success in these post-industrial quarters. One of the instigators ushering in this regeneration, Daelim-Changgo epitomises Seongsu-dong’s newfound identity. The converted rice mill functions as a café, gallery and collaborative space for locals to talk about new ideas over slow-drip coffees.

Creative director Bohan Qui clocked the suburb’s renaissance early on: “In 2018 we produced a MR PORTER event in Seongsu-dong – coining it the ‘Brooklyn of Seoul’ – and our guests were surprised we overlooked the Gangnam and Itaewon hotspots.

“Since then, Seongsu-dong has had a complete explosion of youth culture, new brands and concept stores, and become a breeding ground for new creative pursuits.”

With global brands catching wind and beginning to ‘pop-up’ in Korea’s most-hashtagged precinct, in 2017 local policymakers enacted anti-gentrification and rent control policies4 to protect residents and culture from rising real estate costs and erasure. The Red Brick Landscape Preservation Project,5 a localised urban revitalisation policy, was also introduced to preserve existing built character and to ensure all new and refurbished builds stacked up to the local aesthetic – just like JYA-rcitect’s ‘Wave’ building.

A project that balances preservation with present-day purpose is Seongsu Yeonbang, a former chemical plant redesigned by FHHH Friends as an incubator for small creative businesses. For architect Han Seong Jae, a ‘light touch’ approach to preserving the building’s industrial charm was a no-brainer.

Redesigning this creative complex to host bookstores, cafés, and artist’s workspaces was driven by a design outcome for greater connection and collaboration between tenants and the wider community; “I dreamt of a place that was well-loved regardless of current trends,” reflects Han Seong Jae. “We added balconies to connect both buildings, widened aisles for wheelchair accessibility, and reimagined the internal space lined with trees and greenery for community gathering.”

Seeding modern arts and tech in Poblenou, Spain

Coined the ‘Catalan Manchester’ as Spain’s industrial epicentre, the beachside precinct of Poblenou fell into post-war disrepair and was largely abandoned by the late 20th century. Today, it stands as an example of economic and cultural revival thanks to an enterprising approach by a forward-thinking city government.

Modelled off Silicon Valley in the United States, 22@Barcelona was unveiled in 2000; a city-wide revitalisation strategy centred upon enticing knowledge-based activities and foreign investments revamped post-industrial pockets. A precinct overhaul of Poblenou began; extensive land rezoning, communications infrastructure updates, embedding a pneumatic waste disposal system, street upgrades with bicycle lanes and open spaces, and incubator facilities for fledgling ventures to germinate and grow.

“The integration of urban renewal with major events like the 1992 Olympic Games can serve as a powerful catalyst for change, providing both the impetus and funding for large-scale infrastructure improvements,” describes Professor Ignasi Capdevila from the Paris School of Business.

A strategy so successful that it has propelled Poblenou’s status as a booming tech haven, with over 4,500 new businesses setting up shop in the first 10 years; it now boasts one of Europe’s highest density of coworking spaces. Along with the precinct’s technological revamp, land rezoning has made way for the provision for subsidised housing within a more compact city scenario.

Poblenou now harbours Spain’s artistic heartbeat. Stalwart artist-led collectives like La Escocesa, a 1990s collaborative residency space founded in a former textiles factory, neighbours institutions like Disseny Hub Barcelona, Spain’s cultural centre for design and fashion, and Can Framis, former 18th-century factories devoted to contemporary Catalan painting.

Reactivating Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, through cultural programming

An exodus of the banking industry brought Downtown Kuala Lumpur to a stand-still with streets of over 500 dilapidated shopfronts and unkept government-owned colonial and Merdeka-era buildings.6 Enter Think City7, a community-focussed urban regeneration organisation that established an ambitious master plan to revitalise a hollowed-out downtown precinct.

The 2019 Kuala Lumpur Creative and Cultural District Master Plan (KLCCD) was devised with culture-based urban regeneration practices and the potential of the creative economy in mind. As Hamdan Abdul Majeed, managing director at Think City, explains, the KLCCD “seeks to revitalise the historic core of the city” through a participatory approach that knits together heritage, culture and innovation.

Five years on, key initiatives from the KLCCD have seeded creative projects that deeply involved and empowered communities in the process. Artist-led collectives behind Zhongshan Building and Kwai Chai Hong were recipients of the Creative Kuala Lumpur Grant Programme in 2018 and have transformed forgotten downtown pockets with street parties and creative nooks.

Think City collaborated on Pentas Seni Merdeka; a loud, vibrant precinct activation that celebrates cultural heritage and enlivens social spaces through arts and performance. Engagement initiatives such as Creative KL Urban Challenge and Arts on the Move has brought together a multitude of minds – from city planners to creative hackers – to problem solve urban dilemmas unique to the district.

Extracting creativity from coal production facilities in Essen, Germany

At its peak, the Zollverein Industrial Complex, an interconnected coal processing precinct in Germany’s west, employed more than 5,000 miners that facilitated the extraction of 1 million tons of “black gold” annually. After 135 years of operation, a national shift to phase-out coal production saw Zollverein decommissioned in 1986.8

In the 1990s, freelance artists, galleries and cultural institutions migrated to the refurbished, above-ground parts of the complex, sowing the seeds for a more permanent reimagining of the 100-hectare grounds.

Today’s Zollverein sees a playground of activations and artist hubs that commemorate the site’s industrial roots and mechanised architecture. Visitors can immerse themselves in the “Palace of Projects” in the former Salt Store, explore artist and performance spaces at PACT Zollverein, or take a dip in “Werksschimmbad” in the middle of the retired coking plant. From the outside, a revegetated forest featuring Ulrich Rückriem’s stone sculptures and nightly blue-red light projections canvassed across factory facades are contemporary reminders of when Zollverein’s processing fires ran hot.

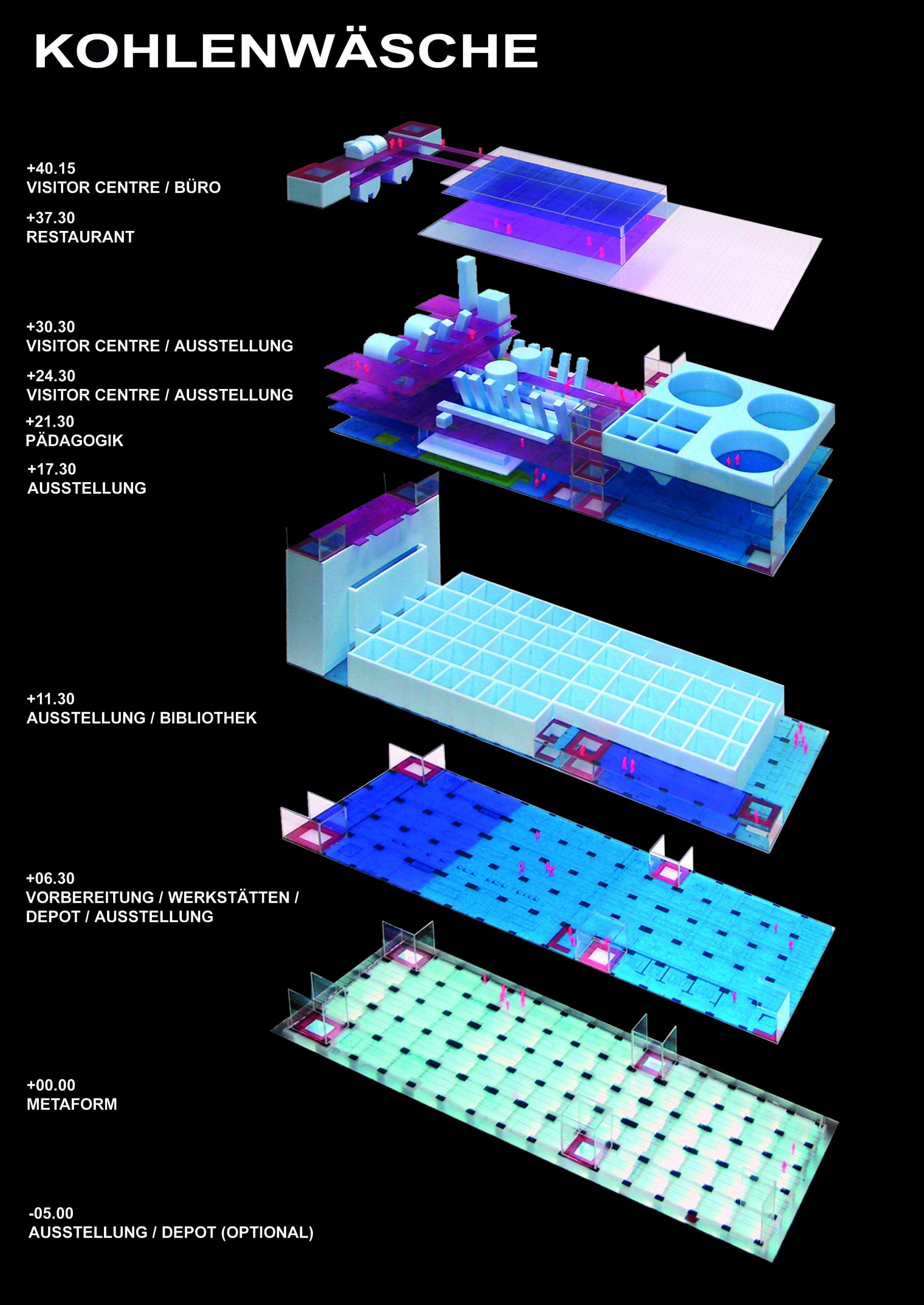

The Ruhr Museum inhabits the precinct’s former coal washing plant and is now a state-of-the-art museum and focal point for the Ruhrtrienniale programme. A 1920s Bauhaus-inspired building that was redesigned by OMA architects with decades of inherited decay and upgrading required. “After closing, the factory workers just switched off and left everything behind” explained OMA’s lead architect Alex de Jong. “When construction work started, we discovered coal had solidified over the years and needed to be removed by a specialized mining crew.”

The OMA team had their work cut out for them – quite literally. Steel-reinforcing bar throughout the concrete structure was entirely replaced and an insulated facade was built anew for structural and thermal soundness. A freestanding, orange-tinged escalator with a glass chassis now raises museum-goers 25 metres high to begin their tour experience, as an ode to the past. “The flow of the visitors follows the same route that the coals followed when the building was still operational,” says de Jong, highlighting a ‘throwback’ design outcome.

“Slowly but surely the area recovers from its industrial loss and economic hardship and is repositioned as an arts and culture precinct,” remarks OMA’s Alex De Jong. Twenty years on, Zollverein still hums with artistry that commemorates the past and in turn has ushered in a new creative mantle for the Ruhr region.

- A Gothic-style hotel turned vertical community for artists, musicians, and entertainers, one that Patti Smith likened to “a dollhouse in the Twilight Zone, with a hundred rooms, each a small universe” in Just Kids (2010, page 122).

- Florida’s theory from his book The Rise of the Creative Class (2002) is that the economy is transforming, and creativity is to the 21st century what the ability to push a plow was to the 18th century.

- The Accessible Canada Act 2019 established federal law that aims to identify, remove, and prevent barriers facing people with disabilities.

- The precinct was designated as a Sustainable Development Zone to proactively prevent commercial gentrification and introduced measures like voluntary agreements between landlords and tenants for subsidised rent and resident-based committees to limit the entry of certain businesses.

- A multi-year scheme funded by the Seoul Metropolitan Government and conducted by the local government of Seongsu-dong to encourage local businesses to preserve the red brick landscape through incentive programmes.

- An era in the late 1950s where the Malaysian people rallied and sought independence from British governance.

- Think City is a self-described “dynamic think-and-do organisation that collaborates with partners to make cities more people-friendly, resilient, and liveable.”

- It was later adorned with a UNESCO World Heritage listing as a testament to “design concepts of the Modern Movement in architecture in a wholly industrial context.”