Finding community amidst NSW climate and housing emergencies

Chinderah is a tiny holiday town on the southern banks of the Tweed River in sub-tropical Northern NSW. On a regular day, the sun kisses exposed skin with UV rays, the foliage glistens emerald-green, and the river takes its time as it flows through Bundjalung Country. Though the official population count in the 2016 census lists less than 2,000 residents, five caravan parks line the river and two more sit one block away from the shore. Each holds dozens of compact, steel-clad cabins marked by the personalities of their owners, a mix of retirees and young families who can live close to their neighbours and next to the river for the price they paid to own the cabins, plus anywhere from $150 to $250 per week to rent the site – less than half the price of renting an apartment nearby. Kaitlyn Armitage moved to one of Chinderah’s caravan parks 18 years ago with her partner and two children and says it’s the community that drew her in; her neighbours are “like my kids’ grandparents, when their own grandparents can’t be there.” Dennis Cook felt that his small cabin by the river gave him the freedom to enjoy life without worrying too much about his finances. Lester Clark, at another caravan park, first moved there from Mount Isa, Queensland so his wife could be near her sister, and he could spend his days fishing.

On 28 February 2022, this paradisiacal setup turned into a southern hemisphere Venice, as the NSW State Emergency Service issued an evacuation warning for Chinderah: the Tweed River was expected to peak at 2.6 metres the same evening – 10 centimetres above what is considered a major flood level. One hour inland, in Lismore, the flood levels hit record heights of 14.4 metres, two metres above the previous record from 1954. Throughout the Northern Rivers region – from Lismore to Byron Bay, and up the coast to Chinderah and Tweed Heads – more than 3,300 homes became uninhabitable overnight.

Lismore’s levee wall, breached that same night, is 10 metres high. On 30 March 2022, floodwaters breached this levee again.

Nowhere to go

Since COVID-19, the Northern Rivers region – along with other coastal towns on the east coast boasting easy access to the beach, good coffee and infrastructure – has been swept up in the sea change of white-collar professionals looking to work remotely, or a more affordable way of living. As of early 2021, there was nowhere to rent in the area. By April that year, Byron Shire Council declared a housing emergency, and neighbouring Tweed Shire Council followed suit the same month. According to the NSW Department of Communities and Justice, the region has the second-highest number of people living on the street in the state after Sydney – but with less than 10 percent of the population.

The region doesn’t suffer from a lack of housing, however; much of the property market is rented out as holiday accommodation or simply priced out of reach for locals. New developments are located far from urban centres and lack services such as transport. Officially, affordable housing is defined as housing for people on low to very moderate incomes, but increasingly it just means housing, as wages in sectors such as health, hospitality and the creative industries fail to keep up with the rise in the cost of housing – an effect compounded in parts of Australia where wages are lower than in the capital cities.

In 2013, non-profit housing provider North Coast Community Housing published a report that pointed out the disparity between the cost of renting and local salaries. It suggested that if the nine local government areas in the Northern Rivers region didn’t work with the NSW Government to create housing for a local demographic that included people who might be retired, or have to raise a child on one income, or who simply have neither the income nor the energy for a luxury four-bedroom house, then there would be a housing crisis. Less than a decade later, its predictions had come true.

To address this problem, the local council in Byron Shire floated ideas around, including building affordable housing above car parks, turning two council-owned sites in Mullumbimby into Community Land Trusts, and finding land to install dongas and portables. But the planning process isn’t fast. Faced with delays from the NSW Government, by the time the council declared a housing emergency in April 2021, many people, including long-time locals, couldn’t find anywhere to live – some had even started camping in the bush. And in autumn this year, as the flood waters subsided and people returned to rip out carpets and hose their houses down before the mold set in, many knew that they, too, would join the ranks of those looking for a roof over their heads in a market where their options were now even more limited.

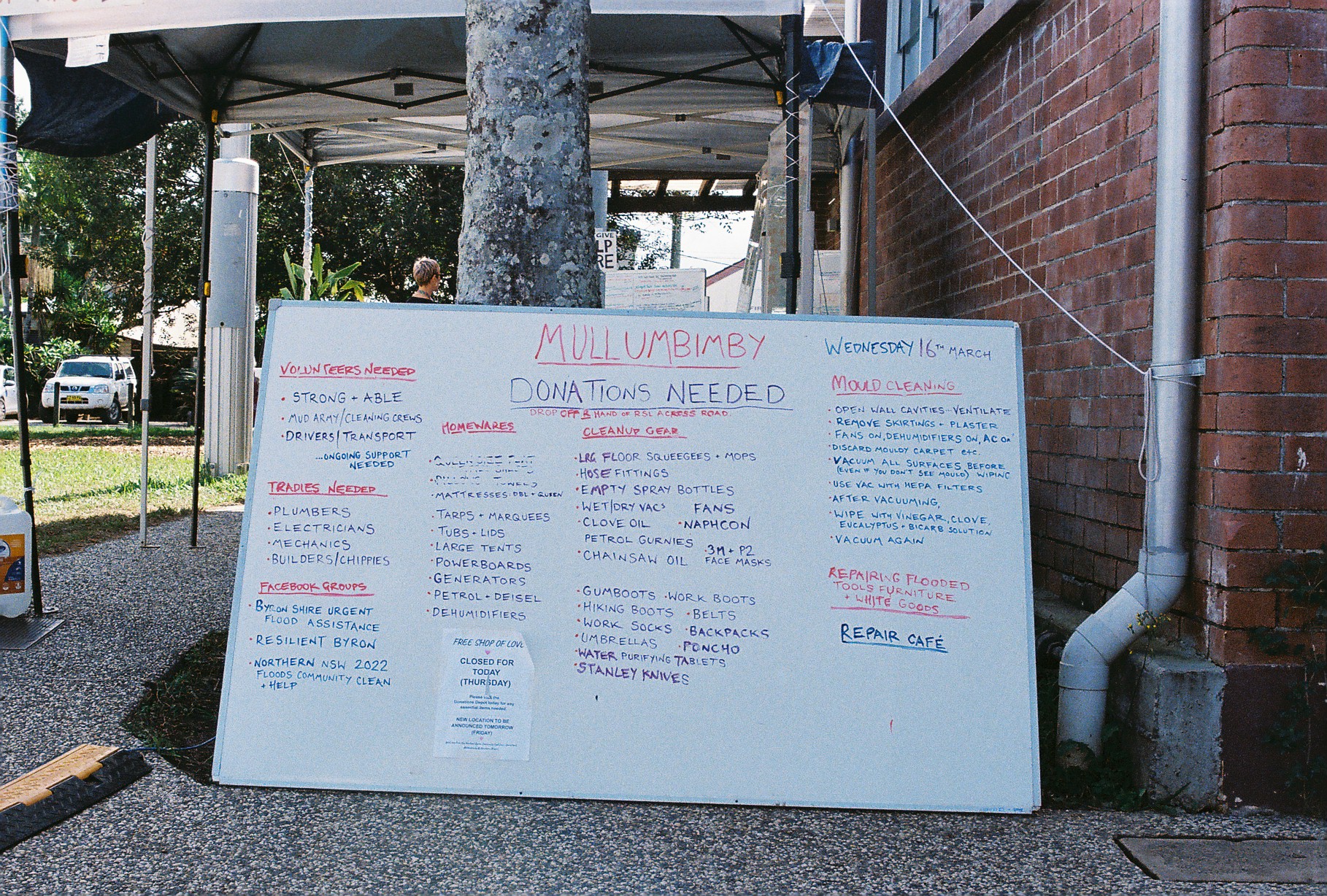

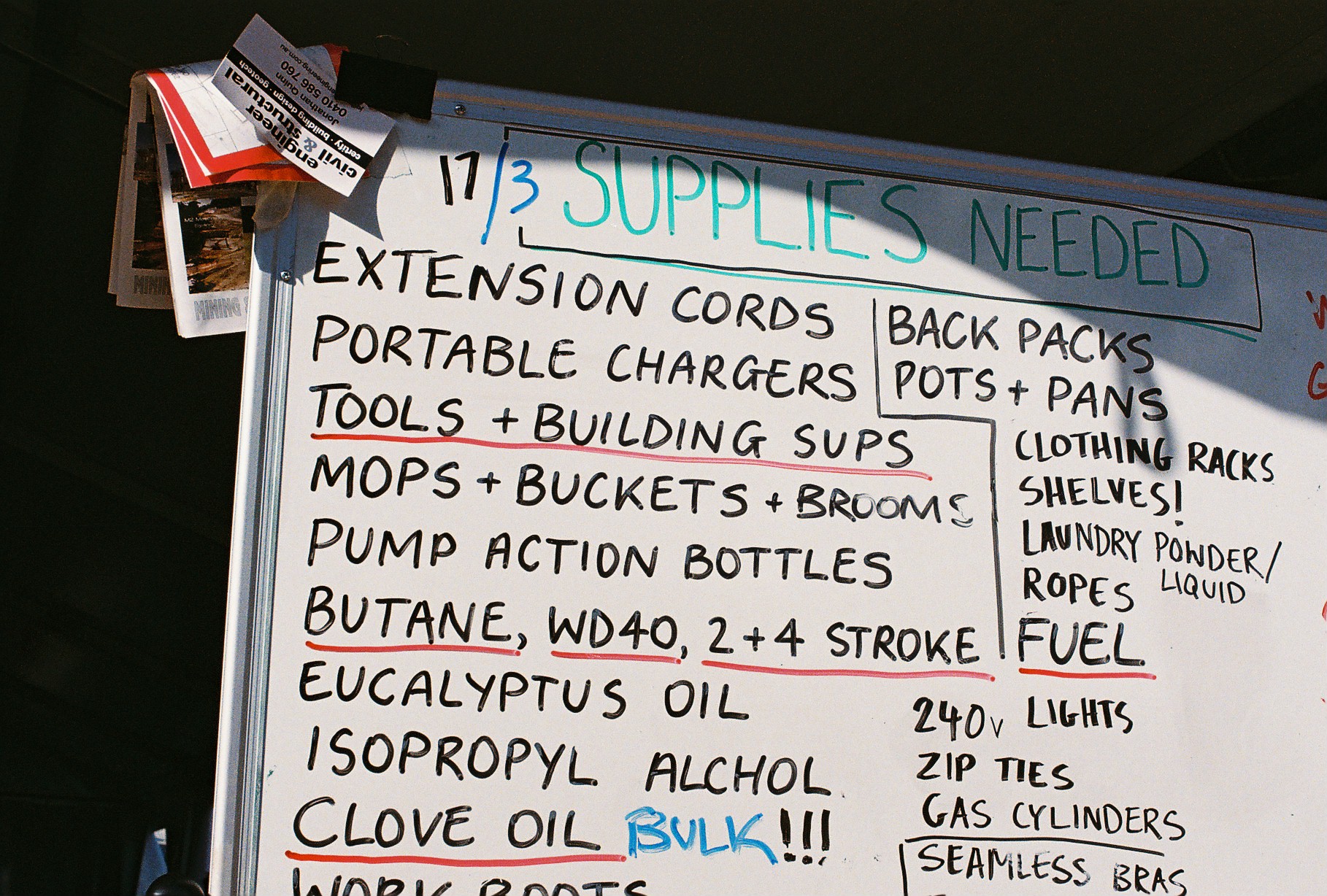

By mid-March in Mullumbimby, the town’s neighbourhood centre and civic hall had been turned into a port of call for all flood recovery efforts. A donations depot sat across from an ‘Op Shop of Love’, where people could recoup necessities; at the entrance to the neighbourhood centre, a volunteer stood inside a booth offering free coffee, tea, chai and brownies to passersby. Next to the civic hall, volunteers sat under a gazebo and stared at whiteboards, listing tasks that people needed done (help with clearing belongings, access to a washing machine) and people with services to offer (chippies, plumbers and even a trauma therapist), scribbling in notebooks and trying to connect those in need. On the street, Australian Defence Force personnel loitered as a traffic controller stopped cars for pedestrians.

Inside the neighbourhood centre, Sylvia Esquiu sat with her laptop in front of her, exhausted. The day after the floods, she had turned up to volunteer with her boyfriend. Because she has a background in social work, she offered to speak to the distressed and traumatised people who came in looking for housing, and try to match them with those offering their homes.

For five days, she did this with a notebook and a pen, until the wi-fi came back. Now, she had a spreadsheet open on her screen, showing the names and phone numbers of people who were seeking housing and those who had offered a space. The spreadsheet was colour-coded like a traffic light, according to whether people needed accommodation that night, in a few days, or in what she called the ‘long term’ – two weeks.

But two weeks wasn’t enough. One particularly heartbreaking aspect of the whole ordeal, she said, was that people would knock on her door hoping to find a place they could actually live in. “We had people coming in saying, ‘Oh, I heard that you could find me accommodation,’” she said. “And I would have to tell them it’s actually relief accommodation, and they would start to cry and say, ‘But where am I going to go after two weeks?’ I think I cried, like, five times a day.”

According to Shannon Burt, director of sustainable environment and economy at Byron Shire Council, this is now the biggest challenge facing each local council in the area: where to house people immediately, where to house them in the next four years, and where to house them beyond that mark.

Right now, Burt said, the council was concerned with finding sites for short- to medium-term housing, which she hoped would buy the council time to find, zone and build housing over the next five years. Some of the land they had previously hoped to rezone and build on would have to be reassessed in light of the floods, and there had been landslides in the Byron hinterlands, leaving the fate of some communities in doubt – all of which would have to be addressed.

In a way, the flood emergency has shone a light on the dire housing situation in the area, with the NSW Government announcing pod homes for flood relief. As Sama Balson, of Byron Shire Council and the founder of non-profit housing group Women’s Village Collective, sees it, “Through this devastation are these little glimmers of hope – where before it was looking like some of these solutions were years away, now it looks like they might actually be here.”

Infrastructures of abundance

In Lismore, the Koori Mail newspaper’s offices, ravaged by the floods, had become the town’s recovery hub. As in Mullumbimby, gazebos, whiteboards and volunteers had taken over the car park; the office’s basement now housed shelves of donated food and household goods. A truck pulled up out the front. “Wait till you see what we’ve got!” a volunteer yelled excitedly at the Mail’s general manager Naomi Moran as he unloaded the van, hinting at a fridge that would allow them to store more food.

Moran sat perched at a desk under a gazebo with her laptop, fielding calls and emails and stopping every other minute to respond to questions, greetings or a hug. She told me, “There is a major housing crisis and homelessness issue here in this region. Now, because of how severe this particular flood has been, we have a situation where there’s going to be thousands [more] people who are without housing – and it’s not like they can just go over to the next suburb and access homes.”

She pointed out that with much of central Lismore damaged, even if people were safe, they couldn’t work. Larger companies with multiple locations, such as Woolworths, Coles and Bunnings, had given staff shifts at other stores, but for those whose workplaces had been in Lismore CBD, there was nowhere to work. “What does that mean for these people, even if homes were available, in terms of rent affordability and daily expenses?” she said.

For starters, changes to rent assistance – more of it, and for a longer period, such as the government’s response to COVID-19 – would go a long way to immediately making sure people had a roof over their heads, said Nicole Gurran, professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Sydney, who spent her childhood in Lismore.

Gurran also points out that there are other lessons that could be learned. “What would be the opportunity to use this huge housing and rehousing challenge [as a way to build and design better], in the way that Cyclone Tracy made houses across Australia safer because of the learnings around cyclone safety?”

She continued: “Because this wasn’t foreseen, it seems there’s no plan. But thinking beyond the Northern Rivers, we need to make sure that all communities that are subject to natural hazards and the risk of sea-level rise, floods and bushfires have a plan in place for periods following that [potential] disaster. We need to know what the options are.

“Right now, in the context of this emergency, wouldn’t it be wonderful to say (and we should’ve done this after the bushfires): ‘Look, we’ve got the infrastructure, we’ve got the homes […], we’ll pay a basic rent to the owners, but part of the social contract of having multiple homes is that people put it in emergency housing.’”

Though housing isn’t the only source of the Northern Rivers’ problems, it is commonly linked. Rebecca Whan, president of the Murwillumbah District Chamber of Commerce, an architect and a regional representative of the Royal Australian Institute of Architects, who accompanied me to Chinderah, highlighted how much the lack of available and affordable housing had compounded the displacement caused by the floods. “Everyone around here knows how to build better in the flood zone – they know the materials; they know the levels. It’s not rocket science.

“But every house here that is in the flood plain – that is, raised above the recommended level – has been built under to provide extra accommodation. They need the income and people need the housing,” she said. “In the old days, that [area] was able to freely flood and clean out, but now all of these people are looking for short- or medium-term accommodation.”

The perfect storm for change

In a way, a flood, a cyclone or a pandemic could all be considered what American cultural theorist Lauren Berlant calls a ‘glitch’ – moments that reveal the cracks in the systems we’ve built around ourselves. “The repair or replacement of broken infrastructure is […] necessary for any form of sociality to extend itself,” they write. As things break, there’s usually an opportunity to do things differently and, as the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction puts it, ‘build back better’.

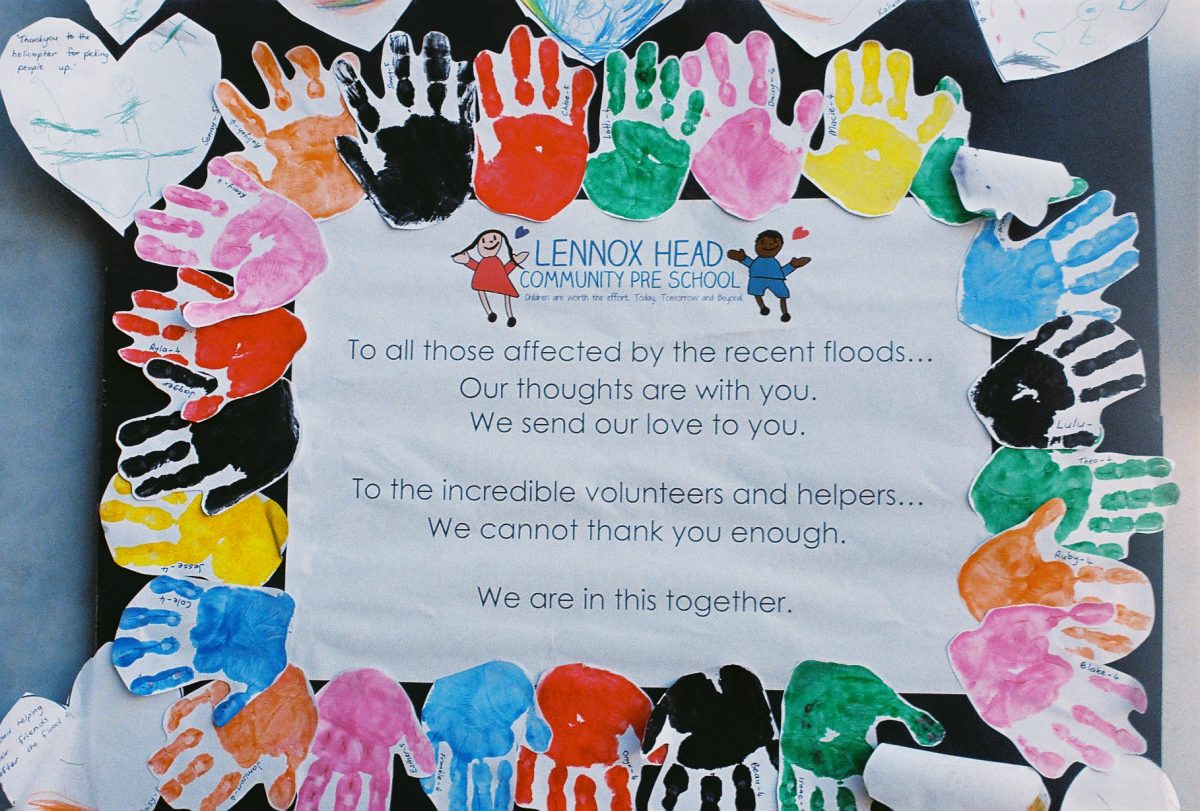

To do this, local councils would need to radically rethink their planning processes. In Byron, Shannon Burt says this would ideally be with the support of federal and state governments in times of emergency. After all, while people might move permanently – as many did after Hurricane Katrina in the US – a lot of people will choose to stay. Connections to community – and to Country – are strong. In the case of Cabbage Tree Island in Ballina Shire, where the floods displaced the community’s nearly 200 residents, Moran said: “It’s not just about people being displaced from their homes. This is about a group of people who have been displaced from their traditional land. We need to get them back onto that island, and we need to make sure that this time around, the quality of the homes that are there are at the standards that any other non-Indigenous community would have.”

By and large, climate change and the housing needed for it — not only affordable, well-designed, climate-resilient homes, but also different types of housing, and the policies to support them — are considered national priorities in Australia. Yet, as global temperatures rise and the atmosphere gains more moisture, there will be more storms in flood-prone areas – and they will be more extreme.

“We have this cultural blindness in Australia: we do not want to recognise that we have a housing crisis,” said Whan. And once a flood or a bushfire hits, Gurran says, “[It’s] going to be much more difficult to recover if your existing housing system is already broken.”

There is no straight path to making sure everyone has a roof over their head or preventing those affected from facing danger from natural disasters again. There isn’t even a guarantee that any attempts to fix things won’t simply act as band-aid excuses to continue ignoring both climate change and the housing crisis. As Berlant writes, “resilience and repair don’t necessarily neutralise the problem, [in fact], “it might reproduce them.” Yet, Australia’s response to Cyclone Tracy and Covid-19 has shown that, if the right decisions are made, we do have the resources, the knowledge, the skills and the infrastructure to do better. It’s never too late to change.