Simona Castricum and the art of ‘queering’ space

In 2018, during the exhibition series WORKAROUND at the RMIT Design Hub, musician and architecture academic Simona Castricum took matters of gender into her own hands.

Creating her own bathroom sign pictograms, she replaced the male and female bathroom signs – with a colleague’s help – with her own signs, that focused on whether or not the bathroom held toilets or urinals. Though the guerilla-style gesture was small, as she later wrote in an opinion piece for The Guardian, it was “the opportunity to make an existing space as non-binary as I could: there would be no space or building function that forced a person to feel as if their gender identity was contested against the normative ideas of male and female.”

It’s a goal that Castricum has maintained throughout her parallel careers, as an architect and graphic designer working at firms including ARM Architecture and the Jewish Museum of Australia, and as a fundamental part of Melbourne’s electro scene supporting international acts like DJ Hell and Terre Thaemlitz. In Castricum’s hands, music and architecture seem less like two separate fields, and more like two sides of the same coin. Her latest album, Panic/Desire, released in June 2020, is the soundtrack to her PhD researching gender nonconforming experiences of architectural space at The University of Melbourne, and SINK, her upcoming performance with video artist Carla Zimbler at Melbourne’s Arts House, uses percussion to destabilise popular conceptions of urban space. For someone who practices architecture like Castricum, who is trying to rewrite the ways in which we move and experience urban environments, sound becomes a way to access a wider audience.

“[Making music] is not a very conventional way to articulate ideas of architecture, but historically it’s worked really well. Look at [Greek composer] Vangelis in Blade Runner, or Wendy Carlos in Tron, and just how well those soundtracks conveyed those worlds,” she says.

“To me, urban architecture has been a place where I’ve almost had to sort of imagine an alternative reality, because how it exists in real life is a bit dystopic for me,” she says.

“Trans and gender diverse people have to live with the consequences of design decisions made by cisgender people who don’t necessarily understand that [experience]. So how do we cut through that?” Not through an 80,000-word PhD thesis, is her answer.

On stage, Castricum likes to perform in body-hugging latex, accompanied by flashing fluorescent lighting reminiscent of Electronic Dance Music (EDM) raves. She describes the music she produces – expansive, epic and pulsating with throbbing, synthesised 80’s beats – as “stadium techno”: techno designed to stake a claim to the stadium arena, a hark back to her childhood in the late 70’s and early 80’s. “I’m from the generation when electronic musicians didn’t belong in the realm of the stadium unless they were burning disco records,” she says. “That was only for rock bands, you know?”

For Castricum, music has always been a gateway to exploring life outside the confines of binary norms. As a child watching Countdown on ABC, the likes of Sylvester, Boy George, The Human League, Laurie Anderson and Annie Lenox dominated the TV screen on Sundays. School was “a very masculine environment where it was all about, you know, guitars, rock ’n’ roll and metal,” she says, where she was bullied for playing New Order’s ‘Fine Time’ on the bus. But she was fascinated by these artists redefining gender norms on their own terms, and saw something of her reflection in these musician’s worlds. A brief flirtation with the drums in high school confirmed her natural affinity for rhythm, but it wasn’t until she started studying architecture, first at Deakin University and then RMIT, that she had the chance to create music. She started by recording sounds and collecting samples with keyboards and guitars. Eventually, she released two albums as the artist Fluorescent, and three more as Simona, including Panic/Desire featuring fellow Melbourne artists m8riarchy and Light Transmissions, released in June last year.

Panic/Desire is the culmination of much of her work in both architecture and music. As an accompaniment to her research into how gender nonconforming people experience the city, the 10 tracks explore “how I move and navigate through the city in the night; how I find a place of belonging – somewhere between my fears and desires,” as she writes on Bandcamp. Drawing from her experiences in the city, her music creates sonic landscapes that convey to the listener the threats trans and gender nonconforming people face in the urban environment.

“Over time, in my emergence throughout music and architecture as a queer and trans person, I’ve had to formulate tactics of survival and music has been one of those. Music not only helps me imagine a reality, it also helps me describe ideas of the city, and helps me to process emotions. So, music and performance become this wonderful way to understand, to process trauma, and to create an empathetic space of shared catharsis with an audience,” she says.

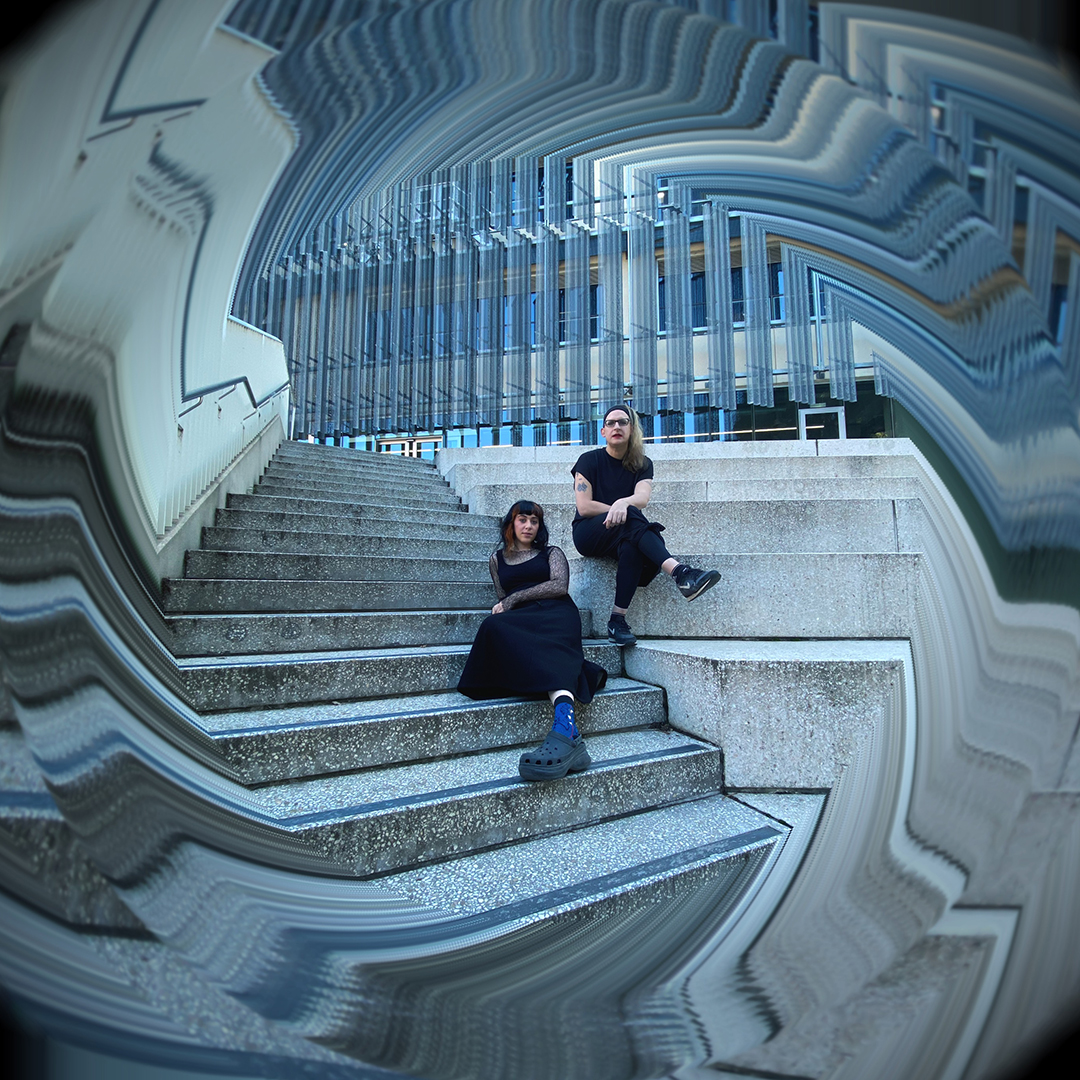

Her latest work, SINK, with video artist Carla Zimbler, brought a glimmer of that experience to Melbourne earlier this month at Arts House. The two artists have performed together before, most notably at Golden Plains Festival 2020 and Live at the Bowl in March 2021, but there, Zimbler followed Castricum’s lead to create visuals for her sets featuring tracks from Panic/Desire and previous albums.

SINK, on the other hand, is a brand new composition and collaboration they’ve been working on together since January, conceived of to challenge urban spaces that, more often than not, are cis-normative and can be hostile to trans and gender nonconforming individuals. It’s an act of queering a space, defined by Montreal-based architect Éloïse Choquette as “a reaction to the status quo, to society’s normative standards – a chapter of the queer movement targeted at architecture specifically,” as opposed to a “queer” space, “a space occupied by queer and marginalised people” – as Choquette acknowledges there may be a lot of overlap between the two. With Castricum working sonically and Zimbler working visually, SINK aims to “explode the hostility off the city, of places, and reference queer space – places of belonging and permanence, of safety,” according to Castricum. Collaborating with architecture graduate Cody McConnell, Zimbler manipulated a 3D model of a fictional city projected onto a suspended orbiting structure over Castricum, who played a full suite of drums and percussion below. Together, their actions combined to “sink” through the hostile normative environment built around the gender binary, a metaphor for how queer and trans space is so often produced.

As Castricum puts it, “If binary thinking of gender uses x and y, well perhaps I’m interested in z – the z axis might be queering and transiting the urban space. It’s a non-compliance.”

Consider the bathroom again, the site of Castricum’s intervention at WORKAROUND and “perhaps the most important private place in the house, [and] also unquestionably the most badly designed,” as Professor Alexander Kira describes in his book The Bathroom. Thrust into the spotlight over a series of “bathroom bills” in 2016 as several US states passed laws requiring people to use bathrooms according to their gender assigned at birth, the bathroom has become a frontline in recent fights for trans-inclusive spaces. In Australia, in theory, people are welcome to use the bathroom of their choice, since several state and territory anti-discrimination laws provide protection against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity. But the law is not explicitly welcoming either: no Commonwealth law exists, and if people are prevented from using their preferred bathroom, there’s not much they can do about it. In March this year, Castricum herself was ordered out of the women’s bathrooms at a Melbourne venue, despite having written the live music venue inclusion guidelines for Music Victoria.

Castricum has been trying to engage with the Office of the Victorian Government Architect to challenge the Building Code of Australia (BCA) to provide accessible spaces for trans and gender nonconforming people. As part of the National Construction Code (NCC), the current BCA specifies the number of washbasins, toilets and urinals a building should have according to the predicted gender split of people using the building. Organisations including LGBTQI+ advocacy group ACON, funded by the NSW Ministry of Health, want companies to label these as all-gender facilities. Unfortunately, the process has been slow, not least because as soon as the word “accessible” gets mentioned, measures to improve spaces for trans and gender nonconforming people become slotted in with people with accessibility issues, creating both a false dichotomy and scarcity in an industry that already has little interest in changing.

But Castricum doesn’t want bathrooms to dictate the conversation. “Trans and gender diverse people carry archives of trauma, and archives of delight as well,” she says. “The bathroom is a space of anxiety in many sites – at the swimming pool, in airports or hospitals – and we need to have those conversations, but the bathroom [alone] is a conversation forced upon us.”

The bathroom is not the only site of conflict, and she doesn’t want “queer architecture” to be reduced to that.

“If I’m gonna be at the table for the next 20 years, asking for a better bathroom experience – which is a sad indictment on the BCA – whose interests are being prioritised? The interests of cis-people. That’s how cisexism and transphobia are enabled,” she points out.

Instead, she wants the conversation to focus on the possibilities offered by architecture: sites of joy, freedom, protection, belonging and safety. These offer “social infrastructure”; sociologist Eric Klinenberg’s term for public use spaces that can and should reduce inequality and build connection, and that exist “outside the bounds of a society built to actively work against them,” as writer Eduardo Rios Pulgar puts it in i-D magazine. Artist spaces have traditionally been places of organising, she points out, and can serve as libraries, community centres and more. Castricum wants queer experiences of all kinds of spaces, including transport, healthcare and recreation, to be considered. She gives queer gyms as an example of how this could work. “I don’t think that queer and trans people have a lot of access to buildings and spaces we can take over,” she says.

Lockdown served to highlight the importance of third places as sites of community and identity: “COVID-19 really highlighted how our entertainment spaces are a huge lifeblood to the queer community,” she says. “The Melbourne lockdown was frightening in no uncertain terms. And I think that it damaged trans people in its own very specific way, because we do rely on connection and community, and we’re not connected to, you know, family in the traditional heteronormative sense of a word.”

In the meantime, she’s excited to be back in entertainment spaces, and for SINK. “You know, I think the people that have come along to some of my shows, have understood something quite profound about my experience – because I can only speak from my lived experience.”

Unlike architecture, “music reaches an academic audience, a professional context, and most importantly it reaches a queer and gender diverse audience, and they can get their own reading of it,” she says. “That’s the beauty of producing art that speaks to the effective condition of humanity.”

This story was produced for our issue #14 Work. To grab a print copy (and pay only postage) head over to our shop.