Creating safer spaces with community in Melbourne’s neighbourhoods

For many of us, moving through streets, during the day or at night, is a complex exercise. Instinctively, we feel out the presence of public spaces which feel unsafe – whether it be that dark patch of the street, the empty corners of a park, stepping onto an almost empty tram carriage or strolling down by the river at dusk.

Our urban environment is complex, and our fears of gender-based violence not unfounded. We carry the stories told through media of women and gender diverse people killed and harmed by gender-based violence, while we consider the many more untold ones. The urgent question is – how do we make public spaces safer and more accessible in real-time for our communities, and for our future generations?

A research group at Melbourne’s Monash University is busy tackling the complexity of building gender sensitive places. XYX Lab, founded by design researcher Dr Nicole Kalms and co-directed by designer Dr Gene Bawden, works at the intersection of urban space, design, gender and advocacy through projects that tackle ‘real world’ problems. Kalms started the lab in 2016. “We noticed there was a lot of work and conversation around violence against women in domestic spaces, but there was a real gap in thinking about public space.” She mentions, “police, sociologists and criminologists were considering public space, but not people with urbanist training. We felt there was room for architectural thinking to insert itself into the dialogue.”

Kalms felt the work that was being done at the time was entrenched in second wave feminist ideas and theory of the 90’s – centred around the lives and experiences of white women. “Just because I identify as a woman and an architect, doesn’t mean I can speak for all women. Until we ask women and gender diverse people about their experience, we can’t know,” says Kalms. Lawyer and researcher Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term ‘intersectionality’ 30 years ago, as a way to describe how race, class, gender, and other individual characteristics intersect with each other and overlap. An intersectional approach to research is at the heart of XYX Lab’s work.

The lab’s cohort is diverse and has grown significantly since it started, with different expertise brought in by architect Timothy Moore, who has a queer focus, alongside co-founder Gene Bawden. Dr Brian Martin, Associate Dean, Indigenousy at Monash University’s Art, Design & Architecture Faculty, is an important adviser. XYX Lab’s PhD students are a diverse bunch, with wide reaching interests in relation to gender sensitivity in our cities, homes, and workplaces. “It’s always about collaboration,” says Kalms. “We acknowledge we have a lot to learn. We can’t be experts in all fields, but that shouldn’t hold us back from doing the work.”

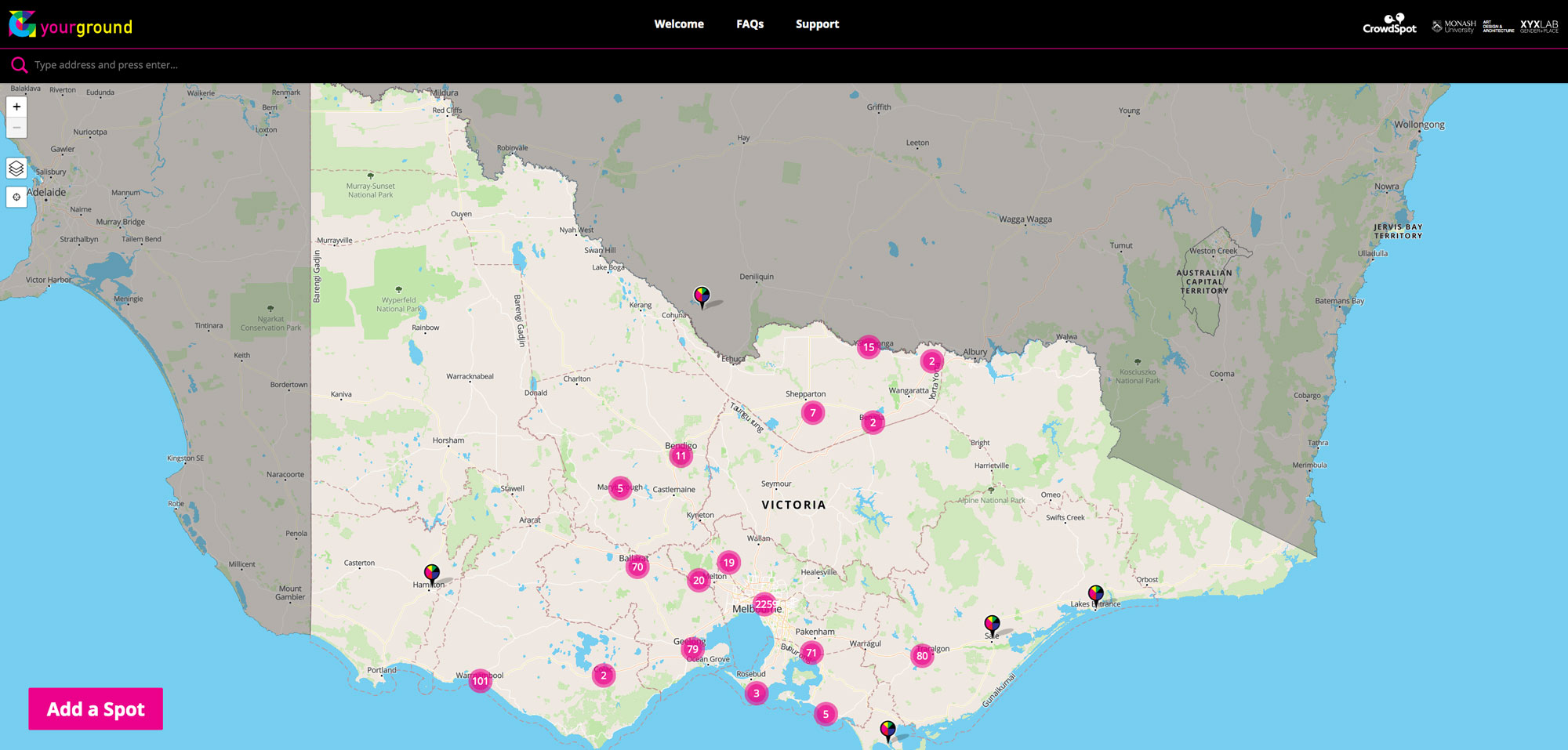

XYX Lab’s current project YourGround reflects this intersectional approach. Made in collaboration with digital consultancy CrowdSpot, the public online mapping project is collecting firsthand experiences of women and gender diverse folk in public space. The project is backed by 20 councils across Victoria, who will use the collected information to inform their planning policies. Type in a location to the map, drop a pin, and be led through a series of questions and prompts for the safety of that spot and an opportunity to write your experience. The interface also has demographic prompts; what you identify as in terms of gender or ethnicity, age range, and employment, for example. All data is anonymous and goes through stringent ethical checks by Monash University.

It is the fourth project by XYX Lab which crowdsources information. “We realise there is a level of exhaustion that women and gender diverse people face at being asked to time and time again reiterate their negative experiences,” mentions Kalms. So, what can gathering this data really do to make public spaces safer for us?

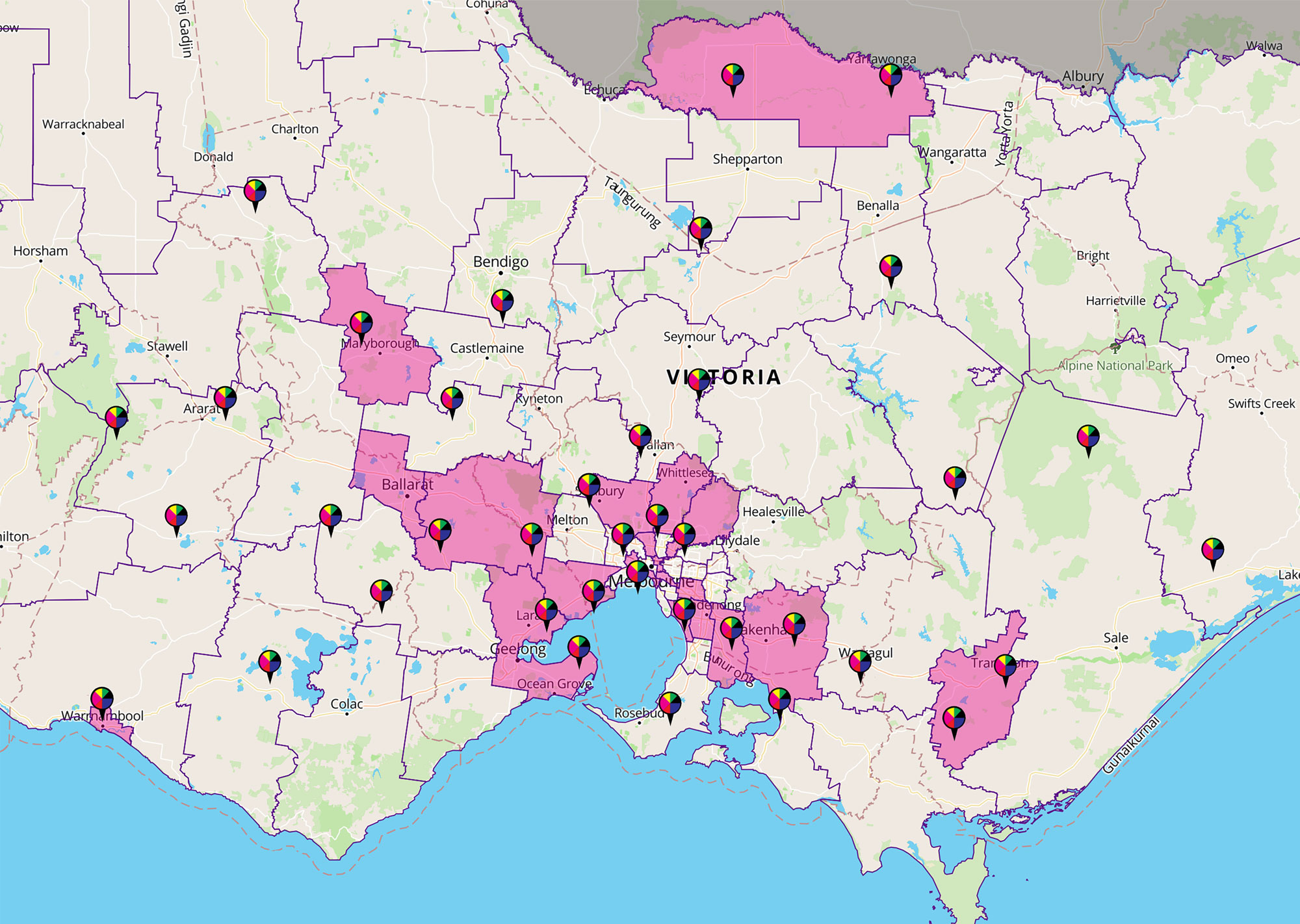

For Kalms, history has taught us that State and Federal Government will not create safer spaces for women and gender diverse people without evidence. “By crowdsourcing information, communities have the chance to speak to people who work with the numbers, to show them the hotspots where they feel unsafe. This data – which is hard to argue with – provides crucial leverage. The next step is to then bring these communities and councils together to design solutions.” YourGround has been well supported by councils across Victoria as a result of the Gender Equality Act 2020, which passed last year, and came into effect in March. The act aims to improve workplace gender equality across all of Victoria’s public sector, universities and local councils, while identifying and eliminating systematic causes of gender inequality in policy, programs and services in workplaces and communities. XYX Lab are also contributing to the roll out of the act by developing an inclusive city training module for professional urban planners to be able to start to develop their skills and understanding of gender sensitivity – crucial education for planners who make decisions for us all.

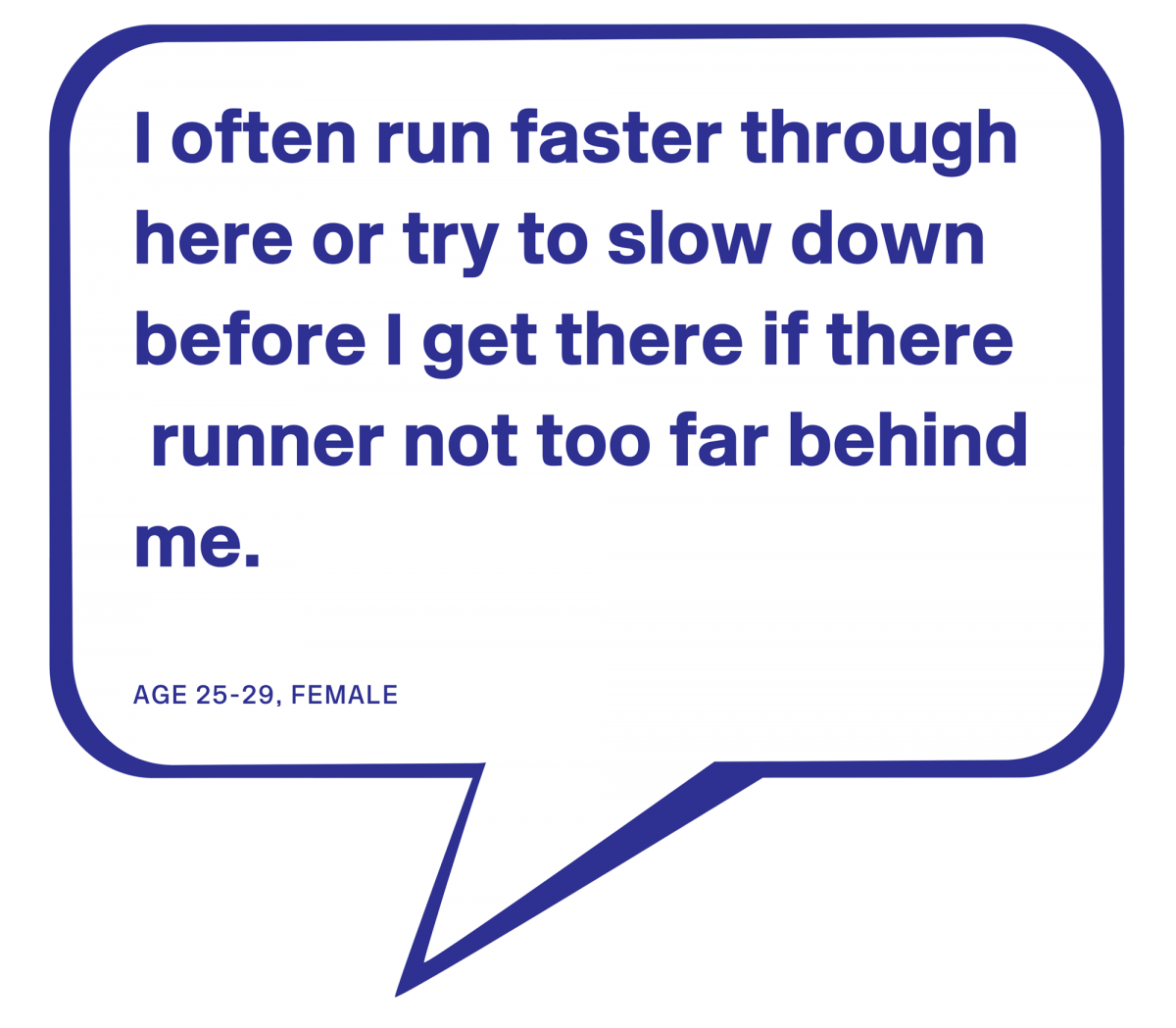

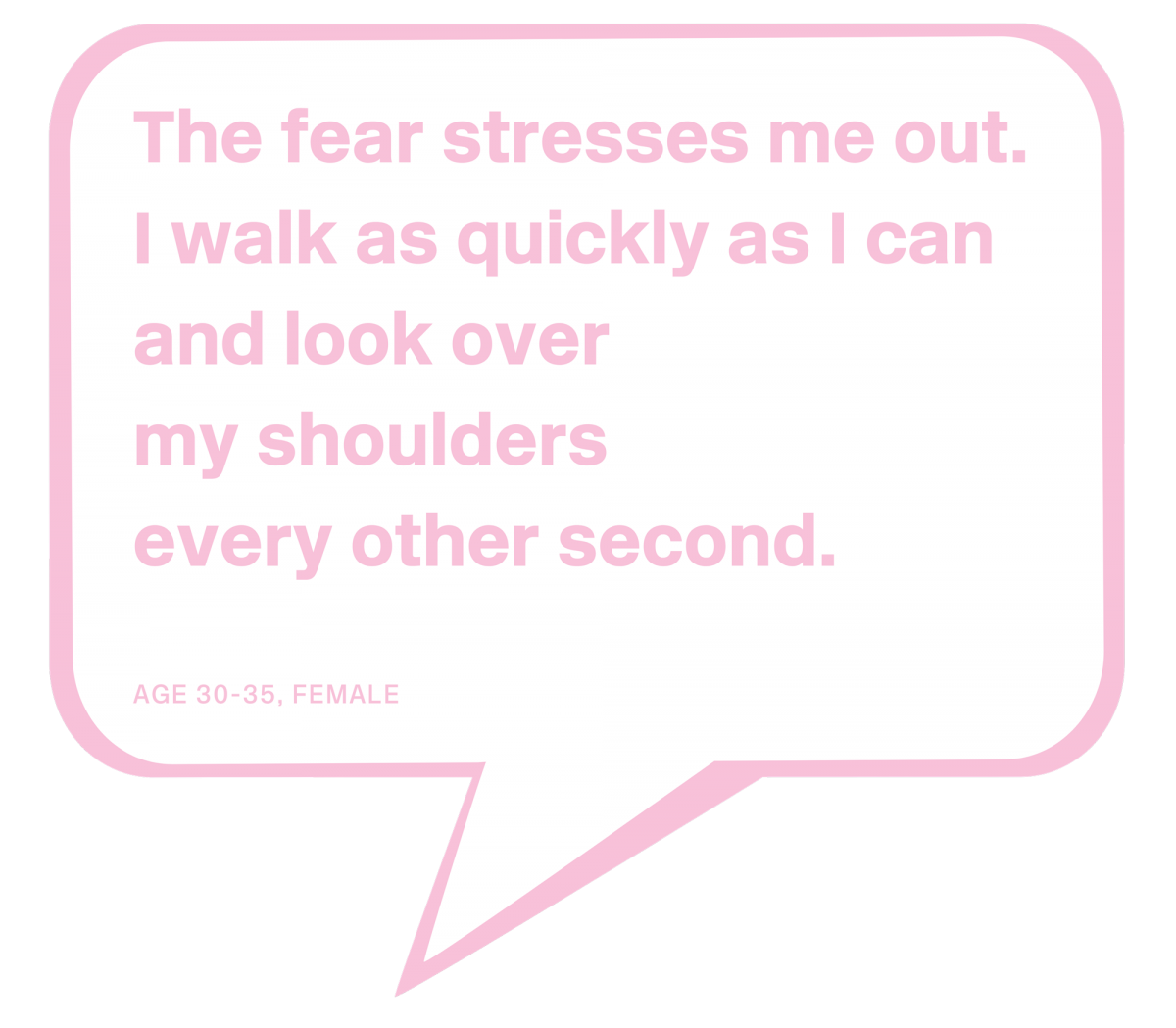

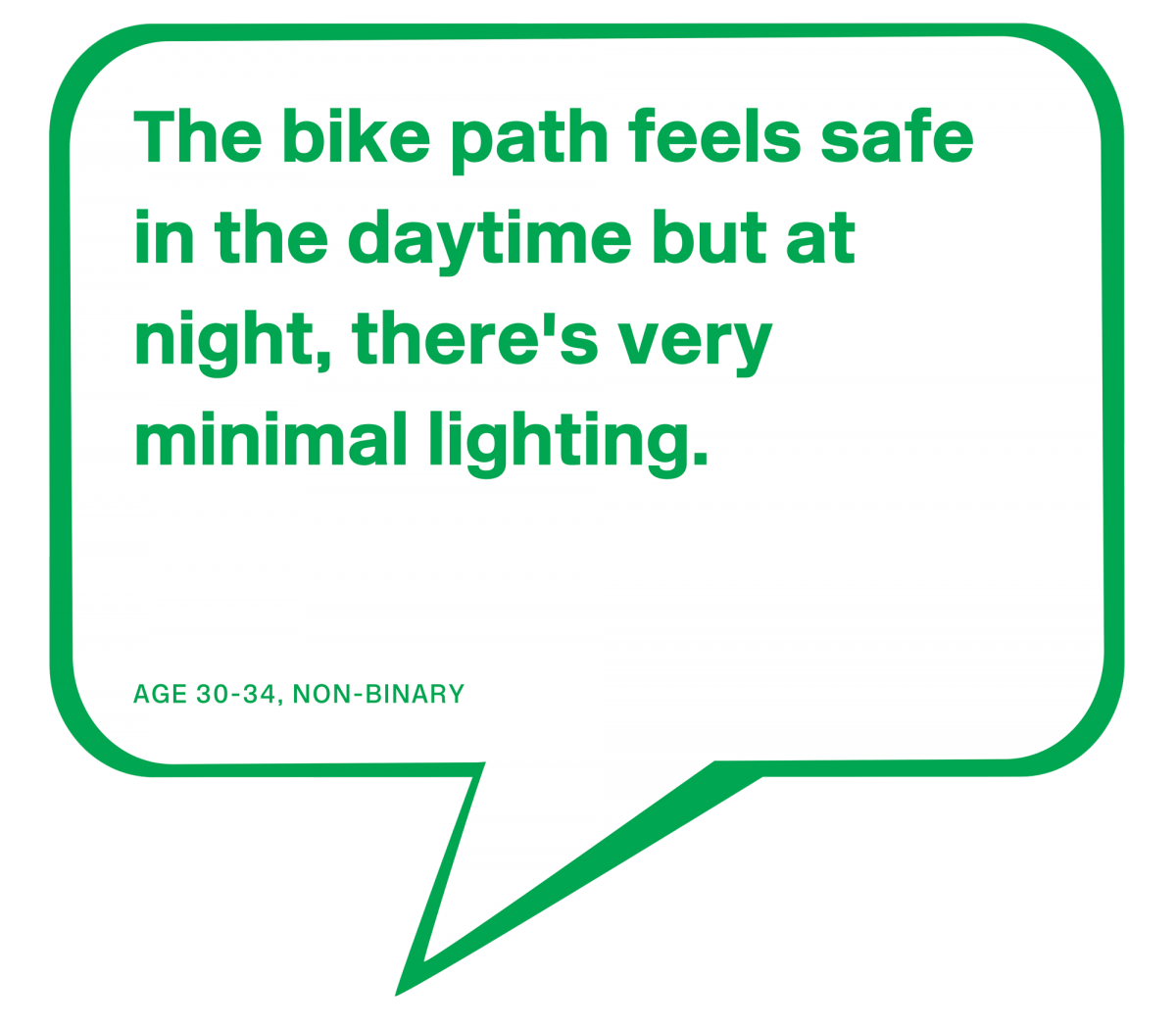

Melbourne’s public spaces didn’t spring from nothing. British surveyor Robert Hoddle laid out the city as a grid at the direction of New South Wales Governor Richard Bourke – when so-called Melbourne was an unauthorised settlement – in 1837. The remnant of that planning is still clear today in Melbourne’s central business district, particularly in the laneways which were created to give access to houses. In many ways we are still living with the unintended effect of this planning, plus years of white male dominated strategic planning with little attention to community need. “The disparity within gender equality plays out in the built environment in particular ways – it might mean that there are places in the built environment that aren’t designed for women, as pragmatic as seats and hand railing’s,” says Kalms. “The way the city is built also affects the way that women and gender diverse people see themselves in the world. We are constantly getting the message that the city doesn’t belong to us, and we don’t belong in its spaces; we don’t feel we have the right to occupy them. Through the work we do, we have observed there is a hyper vigilance for how women and gender diverse people move through public spaces.” Behaviour, societal shifts, and the spatial makeup of the city go hand-in-hand in perpetuating unsafe situations. While YourGround does record behaviour alongside spatial conditions, XYX Lab focus on reporting the spatial aspects they feel they can tangibly change.

Building, or rebuilding, our streets is not the only solution for safer cities. But if not building, what can architectural thinking do? “Architecture is about interrogating social issues”, says Kalms. “Forget the object, focus on the social problems. We, as architects, have skills for translation and transformation. Building architecture can’t solve everything.” Design and architecture are not only about designing for an outcome, it can be as much about designing a process or way of thinking.

While the way our streets, suburbs and neighbourhoods have been planned over time may perpetuate real fear for our safety, this fear is also a consequence of the larger systematic gender inequality that affects us daily. While 80 percent of Australian men report feeling safe walking alone at night, a 2019 Community Council for Australia report notes that only 50 percent of women say the same. As Kalms puts it, “We monitor what we do and where we go. We manage the ways that we move through space. We tell people where we are going; we don’t go out at all. We spend our income on cabs; we buy a car because we don’t want to feel unsafe all the time. These are systematic challenges to just existing in the world.” The hyper vigilance we learn to feel safe in our inner cities is also perpetuated by changing situations. Take COVID-19 restrictions: “Now we are in winter, it is dark by 5:30pm. If you don’t want to go out at night, then your opportunity for exercise is reduced. Then perhaps you use your income to pay for exercise inside, but not if we are in lockdown”, says Kalms. This was one of the reasons why YourGround was launched, “if we can track data about how barriers to public space affect women and gender diverse people’s health and wellbeing, we can build a case for why spatial typologies should change.”

It’s frustrating that change is slow in the face of increasing gender-based violence in our public spaces. It feels like permanent change is only made when there is a violent death or sexual assault in our community. But designing the process and policy for how change can be enacted is the first stage to making long lasting updates. “There must be a kind of permanency to the way we deal with gendered experiences in cities, because it shows everybody that it is significant,” says Kalms. “It’s important. It’s permanent. It’s not just passing us by.” While YourGround takes a long view to making cities more equitable and accessible for all, it is also challenging the status quo and the fundamental processes behind urban planning.

During this year’s Open House Melbourne program, Kalms and the XYX Lab team will present WalkYourGround – roving walking tours across Victoria, that, as Kalm’s put it, “will examine the hidden or silenced stories that need to be incorporated into formal planning and urban design processes.”

This content was produced in partnership for our issue #14 Work, with our friends over at Open House Melbourne | Centre for Architecture Victoria and produced ahead of their 2021 online program Reconnect. To grab a print copy (and pay only postage) head over to our shop.