Government Architect Jill Garner says don’t be afraid of density

Design for civic and for everyday realities have always been at the centre of architect Jill Garner’s practice. Since 2015, in her role as Victorian Government Architect, she has advocated for civic buildings and infrastructure to be considered thoughtfully, acutely aware that design decisions impact Melburnians in their day-to-day lives.

Recently, Garner has been working closely with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) on the Future Homes project. The project looks at the opportunities that lie in building a greater density of housing in Melbourne’s middle ring – the suburbs around 30 minutes away from the city centre. In her mind, to solve the urgent problem of housing scarcity in Melbourne, unconventional solutions are needed. A competition held in 2020 brought together submissions from emerging practices and more established designers to put this theory to the test. A separate competition was run for students to allow for our future generations to be heard.

Sophie Rzepecky

In recent years there have been a series of design competitions across Australia which focus on the issue of sprawl in our cities and speak to the potential of building vertically. New South Wales had one called The Missing Middle and Queensland had one called Density Diversity Done Well. Both looked at how to develop what they call the middle ring suburbs in their cities. What was the initial motivation for the Future Homes competition here in Melbourne?

Jill Garner

In Melbourne, our middle ring suburbs, like Clayton in the south-east or Sunshine to the west, used to be outer suburbs, populated between the 1940s and 1960s during Melbourne’s postwar boom. Over time, as Melbourne’s population grew, the city expanded along its rail lines and modest houses were built on large quarter acre blocks of land. There was pressure to build housing quickly for a growing population, and the housing type resulted in low density, urban sprawl. We really need to start looking beyond the inner suburbs for opportunities to build a denser type of home, and the competition captures

this urgency.

“Density doesn’t need to be frightening.”

SR: The competition asks architects to design apartments, something Melburnians are slowly getting used to in the inner suburbs. Do you think there is a resistance against this in the suburbs further out? Is there a negative perception of density you are tackling with this competition?

JG: There is a question as to how many residents could be living on these large, quarter acre sites. In some homes, there may be only one or two (often elderly) people who can’t manage the upkeep. But the house, land and location may be very valuable to them. And they may be fearful of density and living closer to one another. And they have a point. Maybe the crux of the problem is that discussions of homes and apartments often jump from considering the single house on a huge block of land to a high-rise building without showing how good the middle ground might be.

Melbourne has some fabulous examples of denser housing, including the incredible apartments and higher density living from the 1930s and 1940s in suburbs like Elwood. It is interesting to look at Elwood from Google Earth because it is one of the greenest suburbs in Melbourne, despite being one of the densest. It has an incredible natural system that is layered with occupation. I call this attractive density. There are examples of buildings with say 10 or 12 apartments, where everyone shares the garden, and entry points are a careful mix of public and private, and the place becomes a community. Density doesn’t need to be frightening. We have not learned enough from suburbs like Elwood.

SR: So, is it a value perception that needs to shift?

JG: Australians are very focused on property as the foundation of prosperity. Stability for many people means home ownership. It’s been pushed by our banks and by the way our economy is structured.

The stigma attached to renting is outrageous. This overarching idea that people who rent are second-class citizens or in a holding pattern until they can afford to buy is holding us back. A cultural shift is needed, but we need to be shown good examples of what living in different types of homes could look like.

“Home for me is somewhere where I am not frightened to step outside my front door at night. While it might be a place of respite, it is not a fortress from its place. Home for me is feeling like I am part of a community.”

SR: Why ‘future homes’, and not ‘future housing’?

JG: The competition is a next step towards improving the amenity of our apartments, which was the ambition of the Better Apartments Design Standards (BADS) developed by DELWP in 2017. We talked to them at length about the idea of taking the apartment standards to the next level and testing them on a different model. We chose the word ‘home’ because in the end that is what we are providing. Home is not a hotel room, or someplace temporary; there is a level of permanence and security when we talk about home. And that’s whether you own it or not.

SR: What is home for you?

JG: Home for me is somewhere where I am not frightened to step outside my front door at night. While it might be a place of respite, it is not a fortress from its place. Home for me is feeling like I am part of a community.

SR: There is quite a long legacy of architects designing homes as a service in Victoria; homes for people and not only for profit. Robin Boyd’s Small Home Service established in 1947 is an example. But now, only 5 percent of residential homes in Victoria are designed by architects. Is the intention of the competition to reposition architecture or good design as an affordable service?

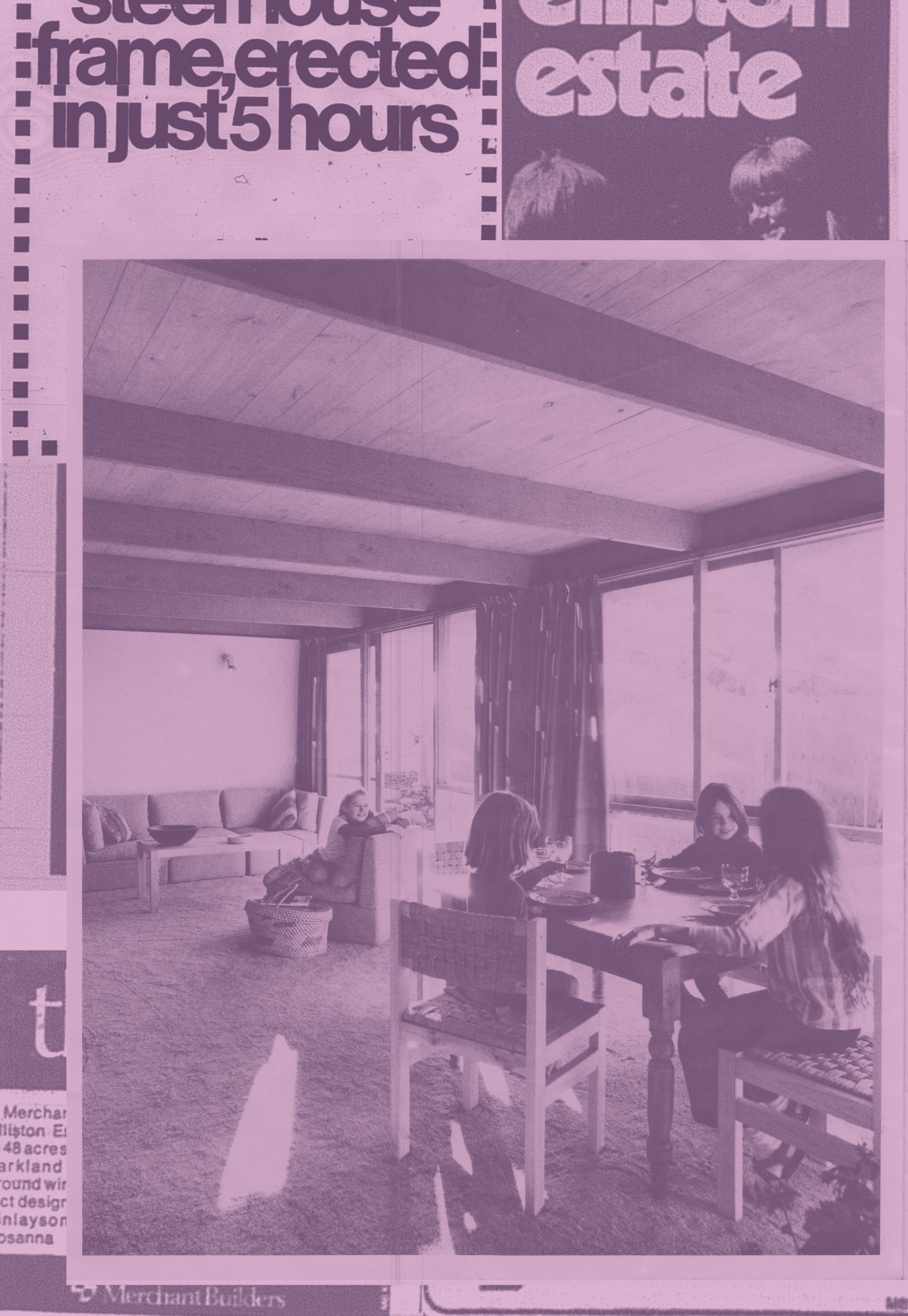

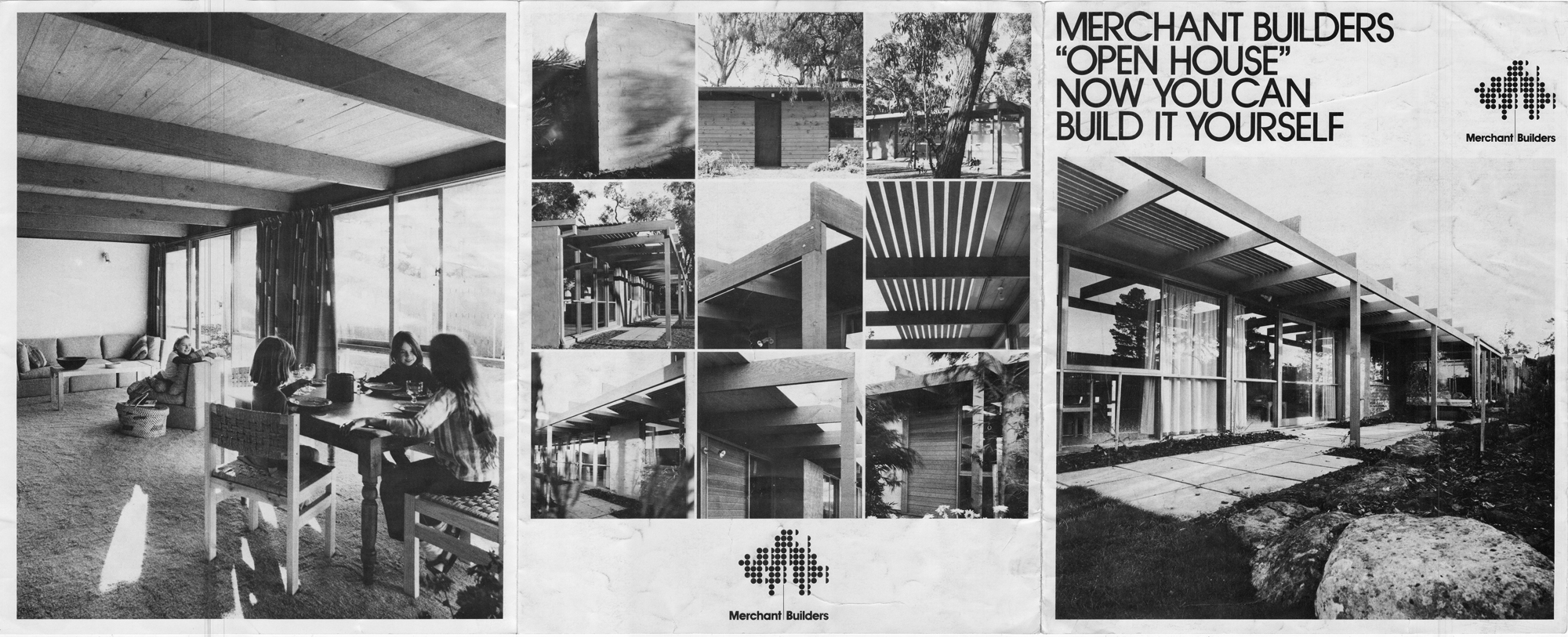

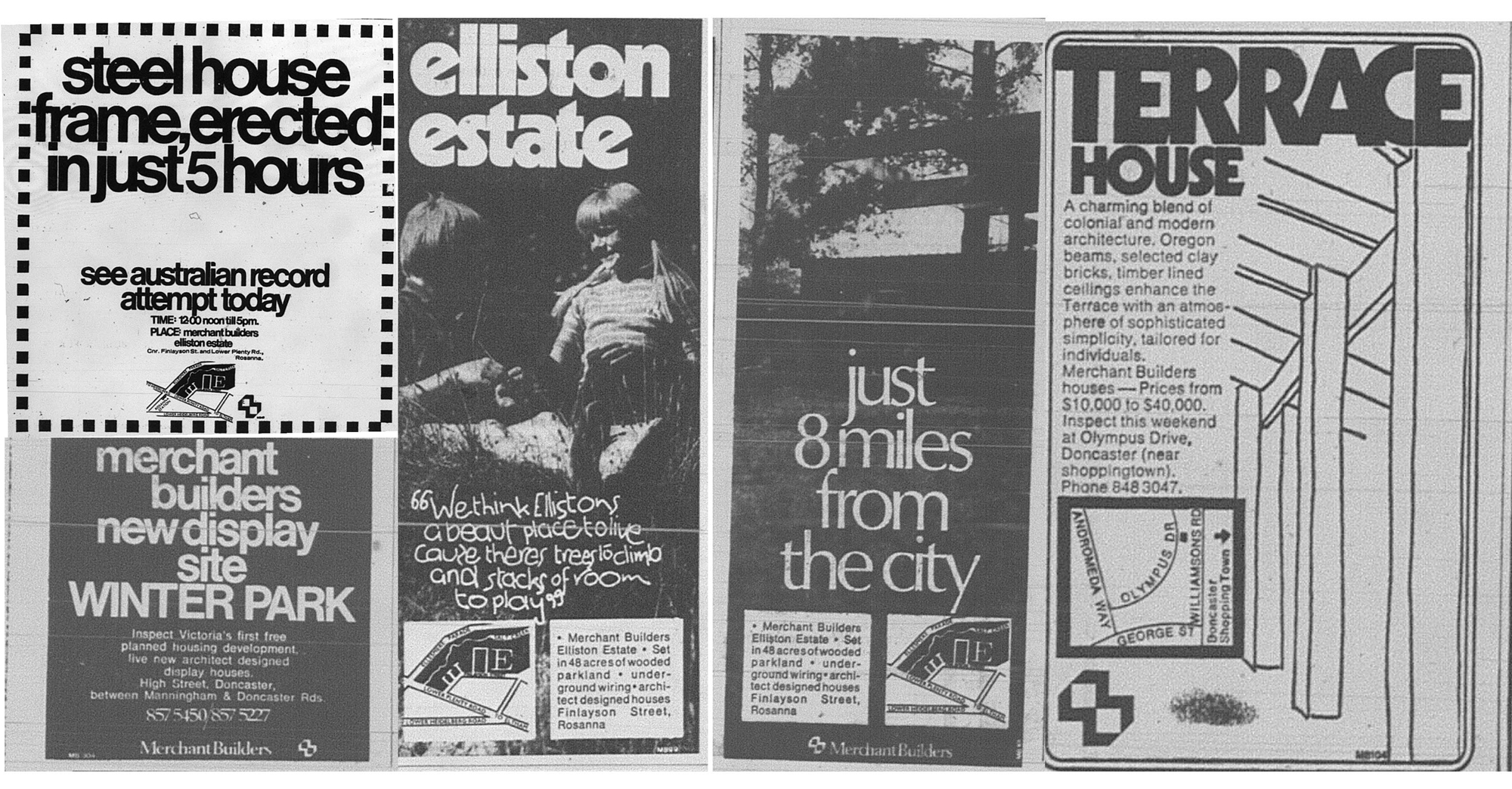

JG: One example you haven’t mentioned, which I think is probably the most important, is the Merchant Builders1 project during the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. It was extraordinary. They were ‘kit homes’ with different components which could be put together in all sorts of configurations. The owner could shift the elements around to customise the design. They were full of light and good airflow and they considered the relationship between indoors and out. Designs focussed on amenity – the good things that we should always consider in designing for living.

Merchant Builders also investigated ‘cluster development’. They would build 10 or 12 homes on a big site and design common areas. These projects put homes and families together in a place that had shared space, private space, communal space, all carefully designed within a landscape. And many had no fences.

SR: Almost like Ikea for homes?

JG: Yes, and they were somewhat affordable because they aimed to be mass manufactured. Many are still left in Melbourne and still occupied – some by the original families. They get passed down, people leave them to their kids, and a new generation occupies the home. They’re a really important reference for this competition. At the time, they brought something very unconventional to Melbourne.

SR: For Future Homes, was there any public or citizen engagement in the development of the competition brief?

JG: The brief drew upon the feedback from the BADS, which had significant industry, stakeholder and community consultation. At one stage, during the development of those standards, it was suggested we would put a spanner in the works of the development industry by making them jump over hurdles. But in fact, it seemed to be an important community awareness campaign in a pressured development market. What we were really trying to say to the community was “Look at the options you are being given; you don’t have to accept poor amenity.”

Many people can’t read floor plans and they put so much trust in the real estate industry. We have heard of people buying an apartment off the plan, moving in, and realising they don’t have transparent windows – they may be frosted because they are so close to a neighbour. They don’t know that they can’t get a queen size bed in the bedroom. They discover they don’t have any storage.

The competition brief took into account the 16 standards within the BADS that were identified through community engagement. We then also took into account the Better Apartments in Neighbourhoods Discussion Paper, a companion to the BADS launched in 2019, which looks at how a development should fit into its neighbourhood.

“My advice to students is to be always looking and experiencing – all aspiring architects need a combination of observation and curiosity.”

SR: How did you make sure there was a diversity of practices in the mix of submissions?

JG: The first submission was an anonymous expression of an idea, because we really wanted to judge on merit, not on reputation. Out of the eight shortlisted submission, four were from reasonably established practices, while the other four were from emerging practices, or not even practices, but collaborations. We understand one was a couple of friends who teamed up to have a go. We were happy to have got this balance between more experienced and less experienced designers, and many cross-generational submissions. The final four, although different from one another, each had a non-conventional approach. We wanted to see proposals for a different way of living.

SR: Will one of the winning team’s projects will be built?

JG: It is a core ambition. The competitions in New South Wales and Queensland have unfortunately not resulted in winning designs being built. Think of all of that amazing work sitting in a cupboard somewhere.

We thought that if we are going to come up with a slightly more radical way of putting eight or 10 apartments on one block of land, we need to communicate it clearly. We felt unless people could see it, or walk through it, it they wouldn’t be convinced. Floor plans cannot easily communicate how a building will feel.

SR: Were the competition entries designed with the designated site in mind?

JG: Yes, but another aspect to the competition was the idea that the model could be shifted contextually to fit any suburb. The idea of components and repetition, much like the Merchant Builders homes, was a core element.

SR: In June 2020, nine public housing towers in northern Melbourne were put into mandated hard lockdown because of fears around COVID-19. The incident brought to light the lack of quality public housing, and the urgent need for it, in Melbourne. By building one of the competition entries, does Future Homes hope to demonstrate that quality public housing can be built by this government?

SR: Yes. We would also like to make the final plans available to the private sector. They could be built by all sorts of people. We love the idea that, quite quickly, these designs could be rolled out on different sites across Victoria.

JG: How will the winners be able to work on “potential planning reforms”, as stated on the competition website?

SR: With the best intentions, the Residential Planning Code (ResCode) has done some very strange things to design. Over time, buildings over two stories have started to look like wedding cakes as they are designed to require front and side setbacks. There is construction risk in the stepped form, resulting in an incredible number of building defects in Melbourne. Frustratingly for architects, when designs don’t quite meet the rules, a value judgement is made. The people who are making these value judgements are not always trained in design – their judgement can be limited to ticking a yes or no box. Design decisions could better take into account site context. We hope to work on this with DELWP and the competition winners.

SR: A side competition was also run for student entries. Do you have any advice for young people who are now graduating from architecture?

JG: My advice to students is to be always looking and experiencing – all aspiring architects need a combination of observation and curiosity. Architects might be labelled the worst drivers because they are always looking at form, at context, at relationships. But ultimately, you can’t practice architecture if you don’t understand space.

This piece is part of Assemble Papers 13 Mind the Gap, published at the beginning of February 2021. Find the print version of Mind the Gap at cafes across Melbourne, or order a copy from our webshop and pay only postage costs.

- Merchant Builders Pty Ltd: Merchant Builders was a development company founded in 1965 by entrepreneurs David Yencken and John Ridge to fill the market gap for good quality, medium-cost suburban housing. Over the next 26 years, they brought together an impressive multidisciplinary team of architects, designers and landscapers, including architect Graeme Gunn, interior designer Janne Faulkner and landscape designers Ellis Stone. Each home had landscaping, Indigenous planting, site planning and interiors as part of the total package. The ‘kit homes’ were made from factory-manufactured components that could be slightly customised by the owner. Because they could be mass produced, costs were minimised. Merchant Builders was also interested in increasing the closeness between homes in Melbourne’s suburbs. Influenced by American urban theorist’s William H Whyte’s idea of ‘cluster development’ – building homes that were orientated the most effective way for light, airflow and safety, rather than in a row in one direction with a road running down the centre. Through their design, Merchant Builders created what would become small, tight-knit communities of residents