Melbourne’s inner city and the fight for food relief

In recent years, regular outdoor food markets have popped up in Melbourne’s metropolitan suburbs, supporting regional farmers and local communities. At the end of August last year, organisers of these markets found themselves faced with an unexpected predicament. Under stringent COVID-19 restrictions, the Victorian State Government announced that farmers markets were no longer deemed an ‘essential service’. Organisers frantically lobbied government officials to allow their markets to go ahead, with varying degrees of success. Some markets were allowed to open, but those located in local COVID hotspots or held in locations used by emergency services remained closed. The inconsistencies in this situation point to an interesting question: in a crisis, which modes of food delivery and provision are deemed essential?

Many of us who live in cities don’t know where most of our food comes from. And indeed, it’s a difficult issue to understand – the reality is that there are many mouths to feed, and Australia is a vast continent, making transport and logistics costly and complex. Large supermarkets dominate our food distribution networks. According to a 2018 report from Roy Morgan, supermarkets hold a 71.4 percent share of the fresh food market. While chain supermarkets provide us with convenient and relatively affordable food, there are many hidden costs for farmers, the environment and our health and wellbeing. The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARES) research agency has stated that the structure of the fresh food market drives a trend “towards fewer, but larger farm businesses.” Another Australian government document, the 2016 State of the Environment report, identifies that these larger farms “compete for space with natural systems, affecting ecosystem function.” So, while a viable alternative system is difficult to imagine, it’s clear that our current system of food delivery has a lot of hidden costs. The environment continues to suffer from the effects of large-scale agriculture. Meanwhile, all but the largest farms either have been edged out of the supermarket supply chain or are offered unsustainably low prices for their crops. Where does this leave small- to medium-scale farmers in rural Victoria, unable to produce the quantities supermarkets require?

“There is a beautiful sense of community at the markets. Towards the end of the day, they become a massive swap-fest – everyone is so generous to each other.”

Metropolitan Melbourne has a strong permanent market culture – Queen Victoria, Preston, Dandenong and Footscray markets are some examples of permanent food markets. However, regular farmers markets exclusively stocking Victorian produce are a recent phenomenon. Melbourne Farmers Markets, a not-for-profit social enterprise founded by Miranda Sharp, was initially supported by locals who were keen to strengthen their community’s fabric. At the turn of the millennium, the green wedge around Yarra Bend was threatened with development. Residents in the area fought to keep it as an open green space and proposed uses that would benefit them. They won the battle and Sharp established the first farmers market in 2002 at the Collingwood Children’s Farm. Today, Melbourne Farmers Markets operates from six locations around Melbourne – Carlton, Coburg, Collingwood, Gasworks, Alphington and Abbotsford. Prue Clark, market manager at Melbourne Farmers Markets, notes: “There is a beautiful sense of community at the markets. Towards the end of the day, they become a massive swap-fest – everyone is so generous to each other.”

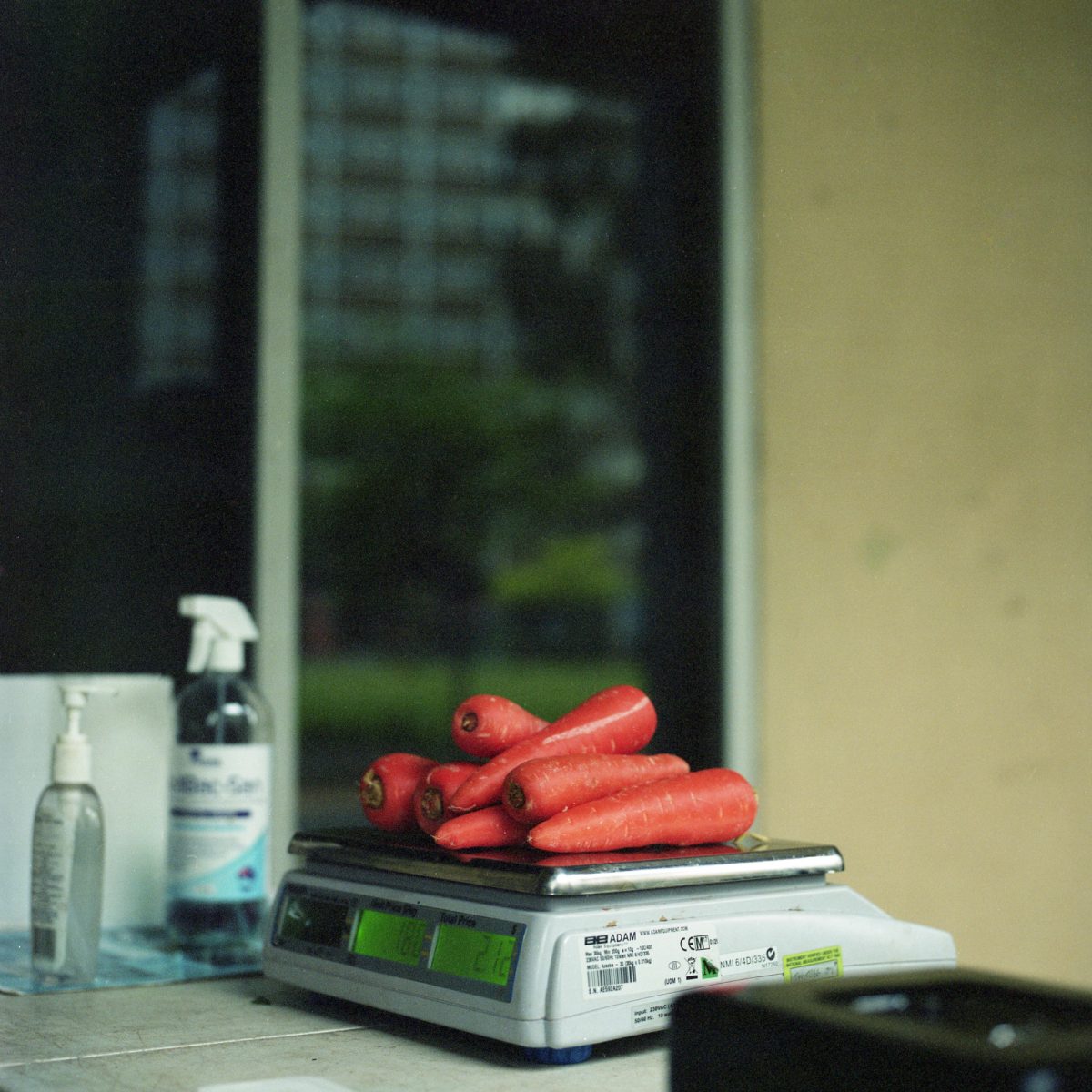

For first-generation farmer Paul Watzlaff, the Melbourne Farmers Markets are indispensable. Without them, he would not have been able to establish his farm, Thriving Foods, in Gippsland in 2016. He explains that many small-scale independent farmers consider the markets as a first rung on the ladder to creating a viable business. The markets create opportunity – wholesalers or local restaurants and stores may stock produce after seeing it in demand. Thriving Foods now has a diversified business model, combining its presence at markets with the sale of produce to wholesalers and fresh fruit and veg boxes directly to customers. The benefits are more than just financial. Watzlaff says, “I often get a bit disillusioned… but it’s enlivening to look at my customers and see their gratitude.” Watzlaff also reports that while many farmers are finding it tough, the lockdowns have been somewhat good for his business, with more people cooking at home and willing to try new things. With the pandemic, he adds, “There has been a renewed focus on having a strong immune system. People seem to want to feel healthy and less run down.”

When you purchase directly from farmers, your money goes straight into their pockets and this has a ripple effect in farmers’ regional communities. While the logistics of selling their produce in the city can be arduous for farmers – long travel times, transport and logistics, merchandising and display, packaging, customer service, point of sale and inventory management – the markets still provide a viable way of keeping some farmers afloat. According to Sharp, an average of $1 million is spent across 150 Victorian farmers and small-scale food businesses each month at her markets. It’s a miniscule portion of the state’s entire fresh produce market, but it’s a vital lifeline for many. Sharp says, “Through the markets, farmers are controlling their own destiny.”

However, the fair price that small-scale farmers need to set at the markets in order for their farms to stay afloat is expensive for many consumers. Sharp is not naive about the conditions that make her markets possible: “The communities where the markets are are fortunate enough to be of a socio-economic profile that is able to afford this food.”

So, how can outdoor markets serve people who don’t find farmers’ prices accessible? Founded in 2014, Community Grocer – another local not-for-profit social enterprise – is paving the way, aiming to provide fresh, healthy and culturally appropriate food, with a dignity of choice, to all communities.

“We need the stepping stones between food relief and the supermarket duopoly of Coles and Woolworths.”

With outdoor markets at a number of locations across Melbourne – Fawkner, Pakenham and Heidelberg West and public housing estates in Carlton and Fitzroy – their model is to adapt to the needs of the specific community in which they operate. When a site for a new market is secured, the team asks locals about their vision for the market and what kinds of produce and goods they would like to have available. It’s an ongoing dialogue, with marketgoers able to request certain products for the next week’s market. While Community Grocer sources all Australian-grown products, the organisation sells from centralised wholesalers – warehouse-scale depots, often in suburban locations, that act as a mid-point in the supply chain between these farmers and their customers in urban groceries, markets and hospitality businesses. Working with wholesalers as one of their main suppliers allows Community Grocer to be more affordable to a wider range of people, and agile enough to fulfill requests. Price comparisons by Community Grocer show that a 1 kg bag of apples from their market is up to 60 percent cheaper than major supermarkets. Due to this increased affordability, people attending the markets say they are eating more fresh food.

COVID-19 restrictions severely impacted Community Grocer’s activities. At the Carlton public housing estate, the markets closed from July until November 2020, with the market space being used as a COVID-19 testing centre while cases were increasing. Local residents who ran small businesses alongside the markets also had to shut. Community Grocer came up with a number of alternative ways to support a community whose movements were so strictly controlled, one of which was to establish a pick-up fruit and veg box delivery service. Every Tuesday afternoon, Tess Gardiner, general manager of Community Grocer, would meet residents face to face to deliver the boxes, and she noted the desire for the market to return was strong.

Many Victorians experienced food insecurity for the first time during the lockdowns. Spotting the gap in the fresh food market, Community Grocer’s services have increasingly moved into the food relief space. “We need that way out,” says Gardiner. “We need the stepping stones between food relief and the supermarket duopoly of Coles and Woolworths.”

They banded together with other food-focused social enterprises, including Melbourne Farmers Markets, to form Moving Feast – a collaboration focused on responding to food scarcity arising from the pandemic’s effects on the economy. When the hard lockdown of the Flemington, Kensington and North Melbourne public housing estates was announced, within 24 hours, Moving Feast was able to deliver 1,000 culturally appropriate fresh fruit and veg boxes to residents.

Though relatively small in scale, the social enterprises that power Melbourne’s regular outdoor markets are an essential service. During the lockdowns, the markets that had to close left countless small holes in the social and economic fabric of the city. They were sorely missed by the residents who use the markets to connect with their community and to access affordable and healthy food. Happily, all impacted markets have now reopened – and it’s just as well. As an alternative food system, these markets imagine the possible beginnings of a different social and economic infrastructure.

This piece is part of Assemble Papers 13 Mind the Gap, published at the beginning of February 2021. Find the print version of Mind the Gap at cafes across Melbourne, or order a copy from our webshop and pay only postage costs.