Loss and looking ahead in Wellington

When was the last time you considered the value of spaces like libraries, town halls and theatres for your city? In Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, the slow erosion of the city’s civic functions over the past ten years has crept up on writer K. Emma Ng. She walks us through this loss, and some vital hope for the future.

I live in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, a compact city in Aotearoa New Zealand where the pace is gentle. It’s the sort of place people leave because it feels like nothing ever changes, before returning, sometimes for the very same reason. I arrived here for university when I was 18. In the 11 years since, I’ve moved away twice – each time mistakenly thinking it was for good. This year, when Covid-19 extinguished any hope of going anywhere anytime soon, I was struck by the dumb realisation that Wellington, the place I’d always thought of as a provisional home, has been the setting for most of my adult life.

For those living further south in Ōtautahi Christchurch, earthquakes in 2011 wrought widespread destruction to the built environment. But not all losses arrive as immediate shocks. Just as I’ve been slow to realise Wellington’s steadfastness in my life, the extent to which this city has changed over the last decade has crept up on me. The post offices have been shuttered, commuters have struggled through bungled changes to public transport, and buildings sit vacant and neglected – victims of stringent earthquake building codes introduced after the Christchurch earthquakes. All of these challenges are particular, but together the effect is a kind of nibbling attrition of the public realm.

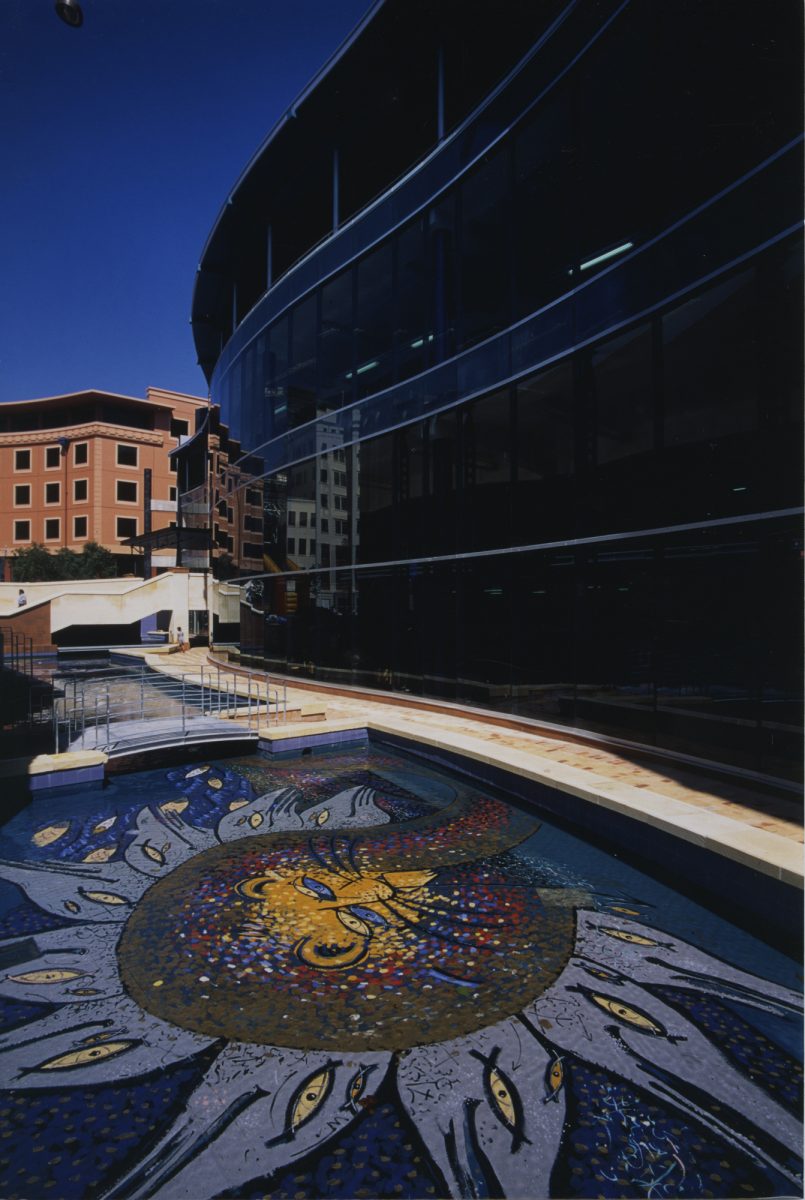

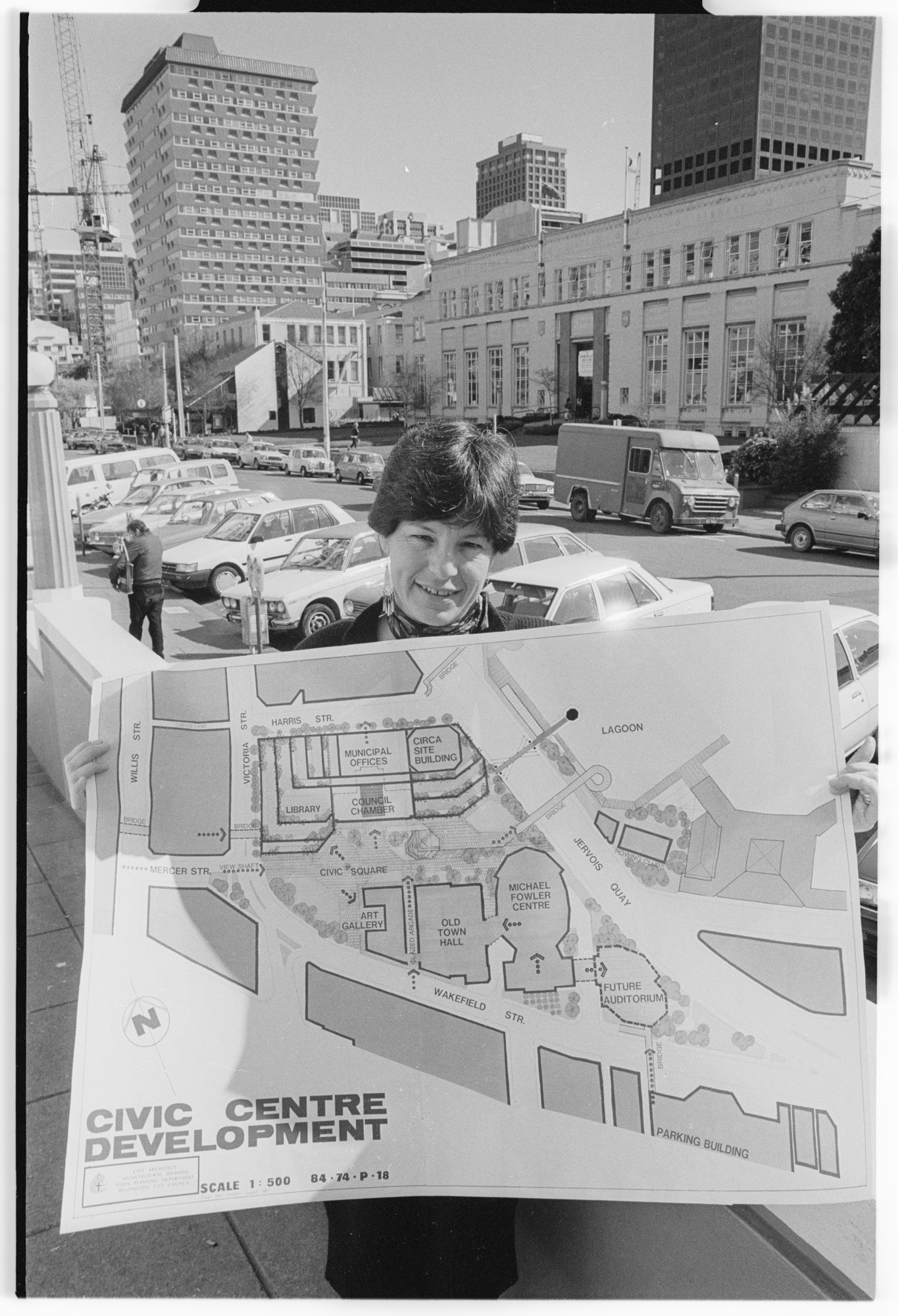

Wellington is small enough that, given half an hour, you can walk from one end of the inner city to the other. It curves around a harbour on its northern side, and is edged in by tree-covered hills on the east and west – physical bounds that limit possibilities for sprawling expansion. At the Parliament end of the city there’s a low-lying CBD that swirls with public servants, while retail and hospitality clusters around the other end of town. A well-developed waterfront runs like a ribbon between these two zones, and at their nexus is Te Ngākau Civic Square, a plaza flanked by public buildings.

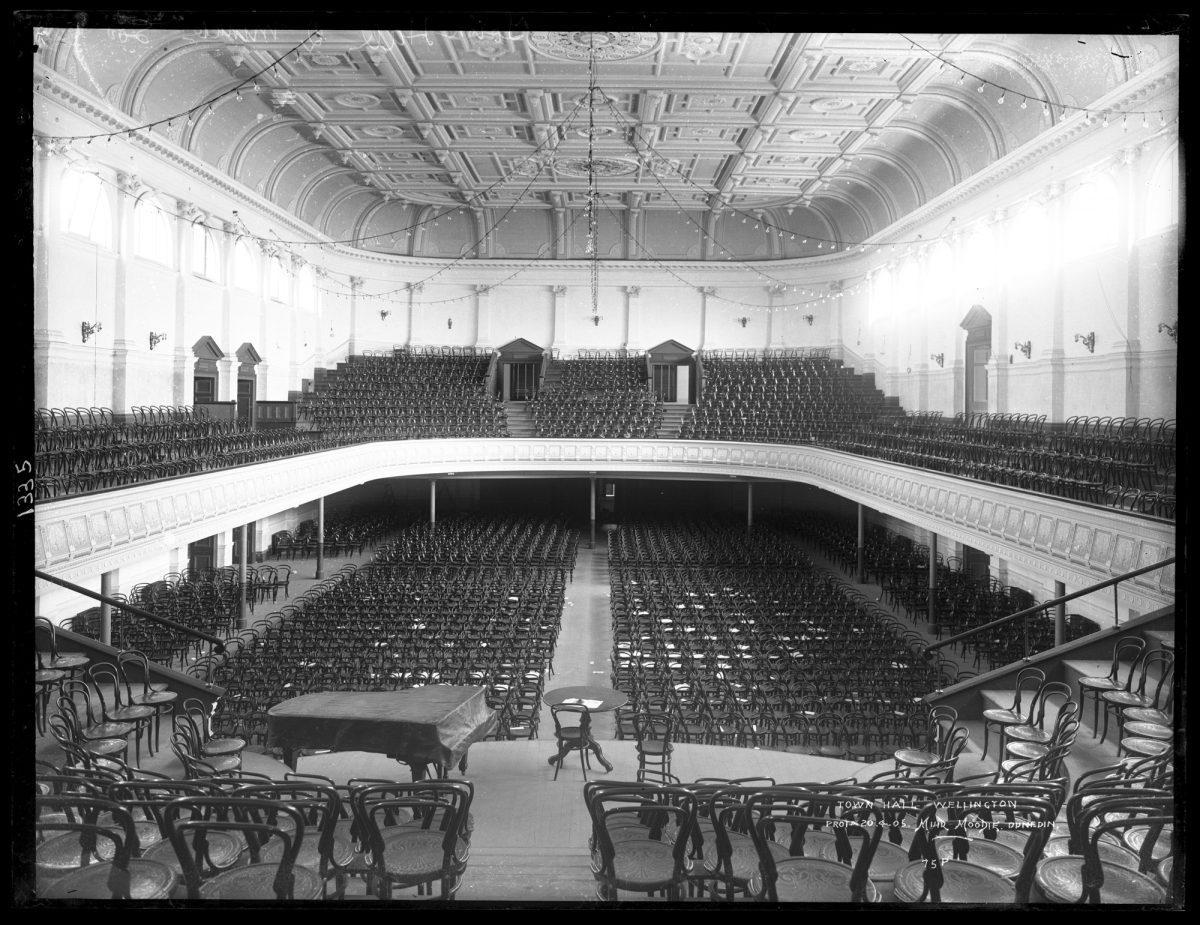

The square, which was developed as a precinct in the late 1980s, has been hit hard by resilience concerns. In 2019, the central library on Te Ngākau’s north-western edge shut down with only a few hours’ warning, on the advice that major damage could occur in the event of a significant earthquake. This followed the closure, on the other side of the square, of the Town Hall in 2013 for ‘earthquake strengthening’, as well as the adjacent council buildings after the 2016 earthquakes (which caused damage in Wellington, though the epicentre was around 200 kilometres away in Kaikoura).

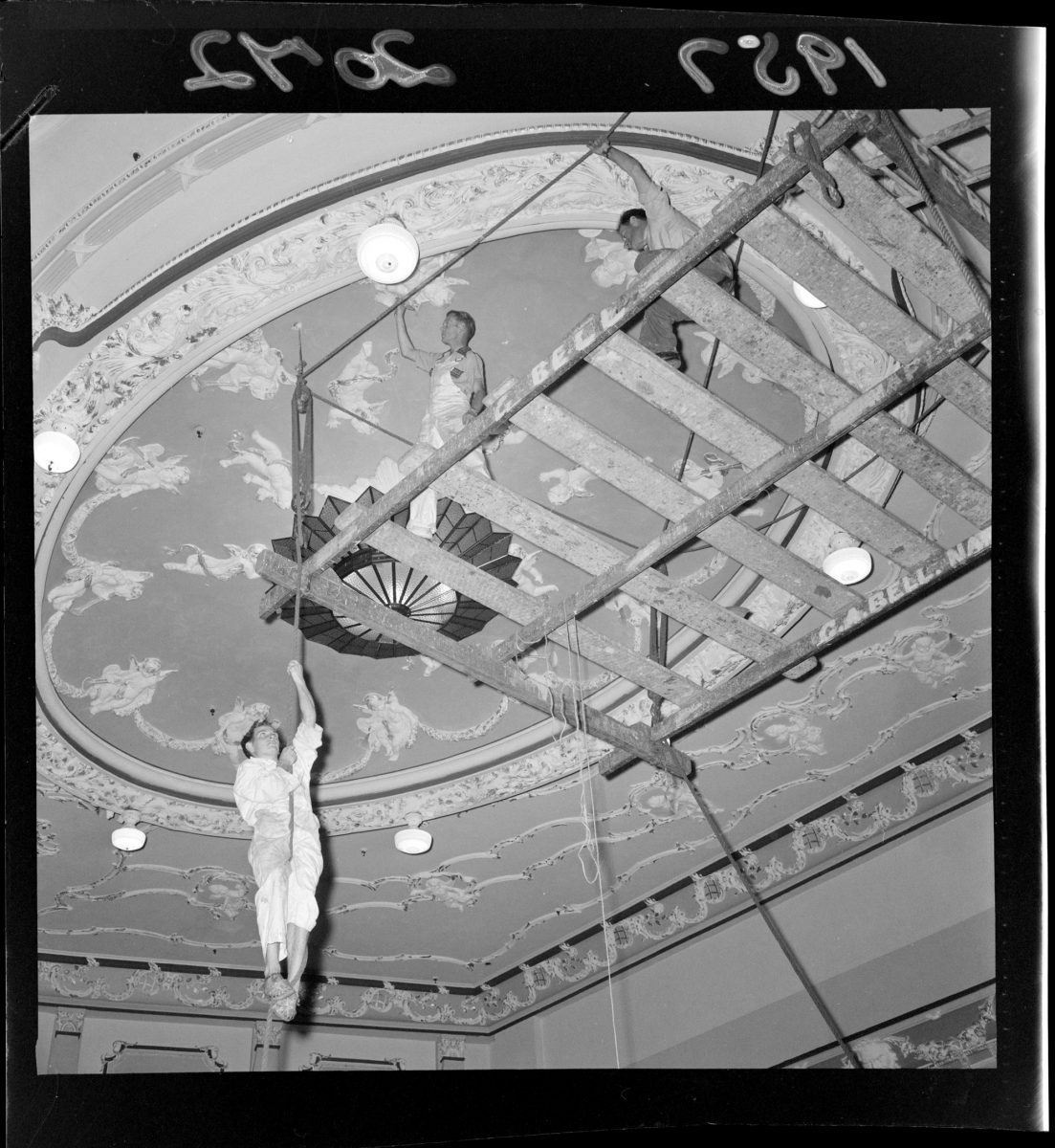

What is lost when the public realm erodes? Most apparent is the primary function of these spaces. For example, the years-long closures of both the Town Hall and the historic St James Theatre for earthquake strengthening has exacerbated a shortage of rehearsal and venue spaces for Wellington performers and events. Stopgap measures, when they are arranged, tend to focus on these activities.

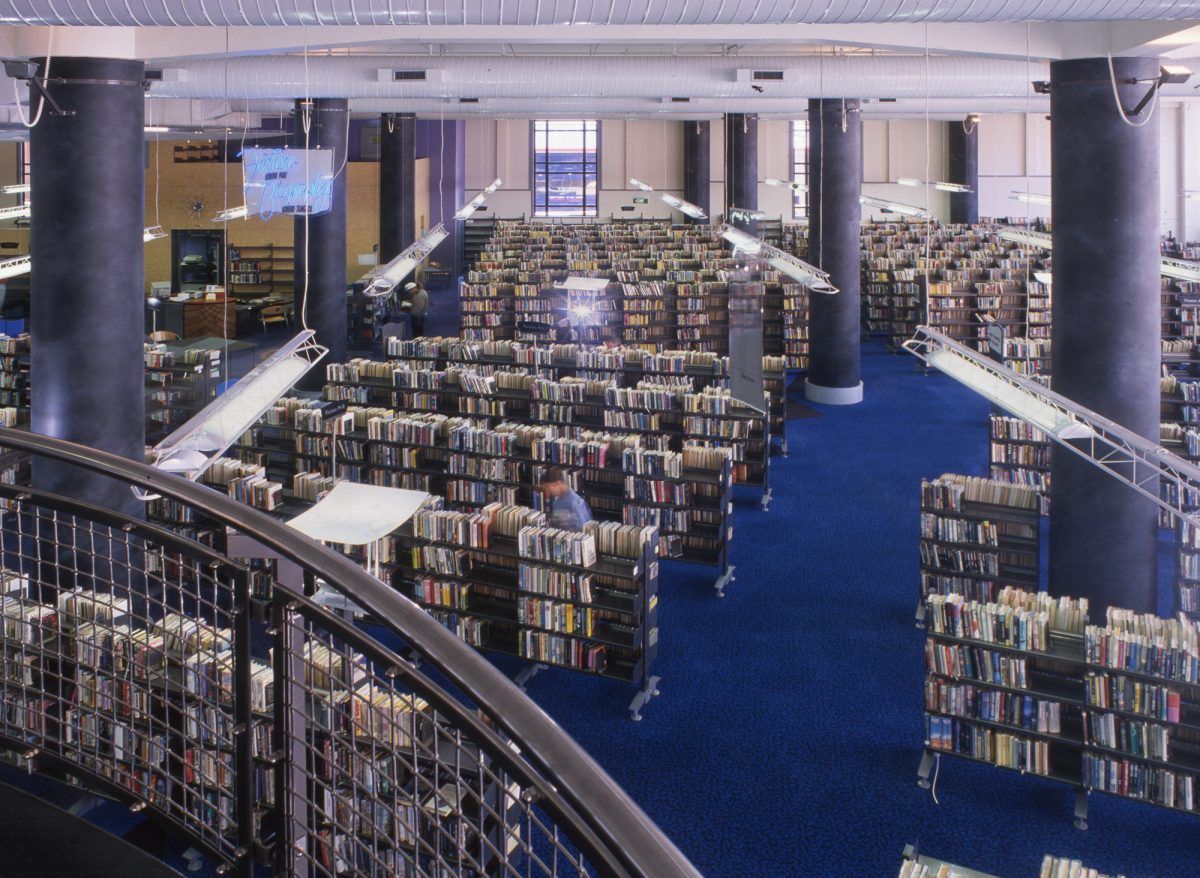

But there is more at stake. What evaporates with these public spaces is a certain kind of trusted civic presence, manifested in bricks and mortar at a community level. I used to joke that the central library offered the best free co-working space in the city, but it fulfilled many community functions beyond accommodating freelancers like me. It offered internet access, migrant support, disability services, a place to access Justices of the Peace and the Citizens Advice Bureau, free newspapers and magazines, a safe place for teenagers and homeless residents to spend time, and regular events for parents and children. Since the library’s sudden closure, Wellington City Council has leased a few smaller spaces in the city to act as temporary libraries. Only some of these secondary functions are accommodated in these new branches.

The post office is another example of repercussive loss. During my decade in Wellington all of the post offices in the central city have closed – a death spiral initiated by falling letter volumes. Instead, you might now post something at a pharmacy, bookshop or dairy. But without the actual post office, I have to think twice about where to buy stamps, where to get a passport photo taken, how to be fingerprinted for a background check, or where someone might pay their bills in person. Visiting the post office might often have been slow and frustrating, but it was also a trusted one-stop shop with numerous secondary functions.

Subject to even less consideration are these spaces’ tertiary functions, which might almost be thought of as social byproducts. This includes basic behaviours such as looking and listening, which were identified by Jan Gehl as activities facilitated by good public space in his book Life Between Buildings, first published in 1971. Gehl understood the importance of these social actions in strengthening the warp and weft of society’s communal fabric. Variations of this simple formulation have been advanced and elaborated by planners and advocates of placemaking for over 50 years. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg’s theory of ‘third places’ (beyond the realm of the home as ‘first place’ and the workplace as ‘second place’) has been particularly influential. He argued the importance of third places – such as cafés, churches, salons, post offices and community centres – as settings for informal social encounters that act as building blocks for community life.

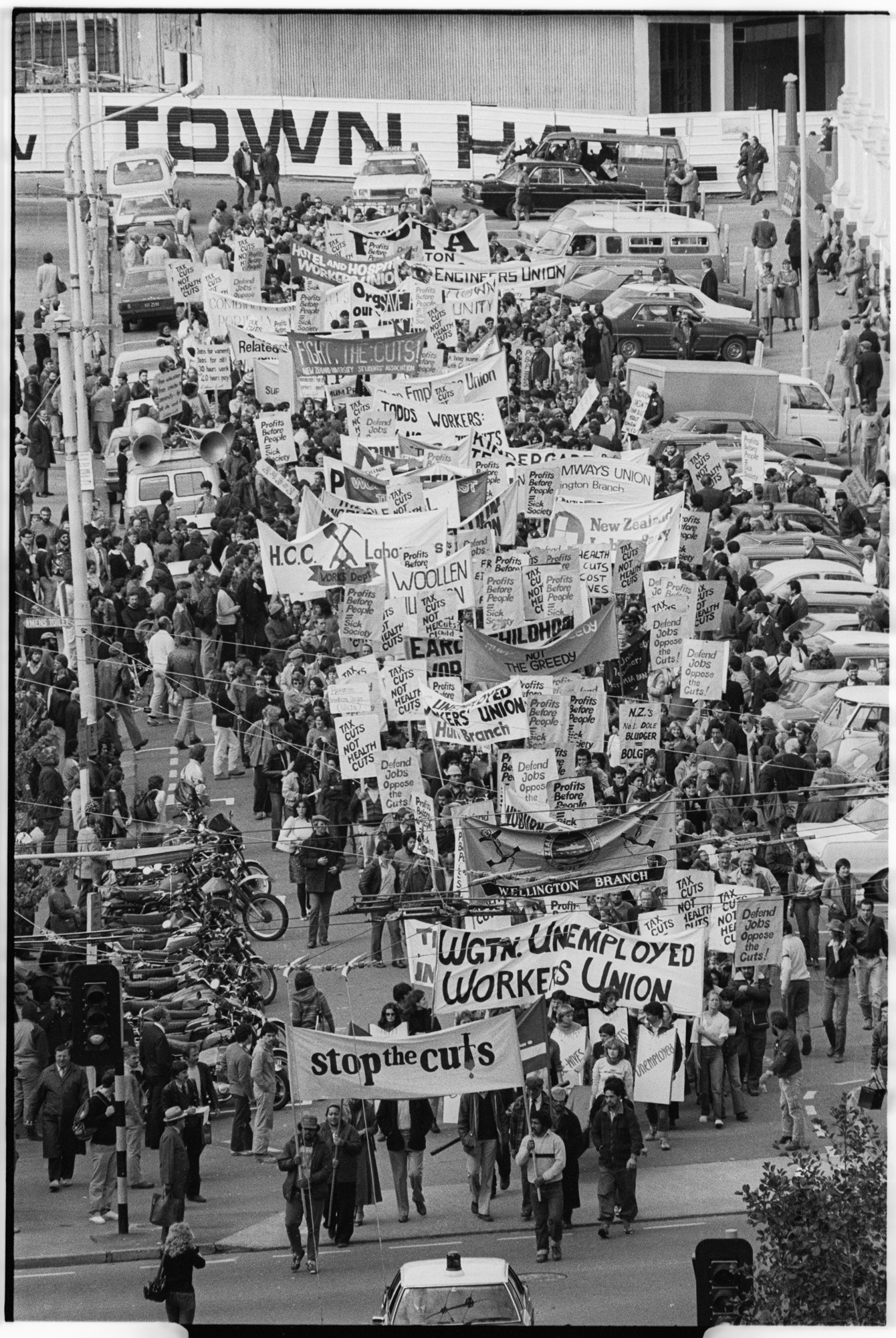

Wellington still has many of the types of third places included in Oldenburg’s expansive definition – cafés, in particular, are fundamental to Wellington life. However, unlike Oldenburg, I’m treating the public realm as distinct from spaces such as cafés and movie theatres (that is, those governed by transaction), which draw in self-selecting groups of patrons, carefully keyed in to subtle and explicit cues of culture and class. The public realm, by contrast, is comprised of spaces shared – not always harmoniously – by a wide range of constituents, representing a diversity of cultures, ages and socio-economic conditions. I’m reminded of political theorist Chantal Mouffe’s contention that antagonism is an overlooked and necessary condition of pluralistic democratic order. When the public realm diminishes, we lose the trusted spaces that act as settings for spontaneous encounters – both affirming and challenging – with strangers and acquaintances.

The end of this pandemic is still not in sight, but the potential to transform our public realm beckons. Crises often prompt us to reshape our environments. As just one example of the public realm thinking that has burst forth during this pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement has brought renewed energy to the debate over public monuments, and the expired values that linger all around us in the built environment.

This year’s racial justice movements cannot be separated from the conditions of this pandemic and the structural inequalities that it has writ large. But the scale of collective change temporarily effected by worldwide lockdowns has also signalled that it is possible to alter the ways in which we live. Lockdown forced us to think together (perhaps seriously for the first time in a generation) about what kind of fundamental conditions enable us to live healthy, happy, sustainable and local lives. The challenge will be sustaining this discourse, despite the temptation to return to the status quo of our ‘normal’ lives.

In Wellington, sanctioned forces of changes are already in motion. Feedback is being sought on the Draft Spatial Plan, which proposes zoning changes that would transform possibilities for residential development. Consultation has just closed on options for strengthening or rebuilding the public library, and transport system proposals are also before the public. But it could be argued that we, the residents of this city, are ill prepared to take up the invitation to participate in these processes. For this reason, we must look beyond these limited windows of local government remediation and consultation to a broader horizon – working to develop our long-term capacity for collective imagination, as well as our ability to debate and articulate our ambitions for the public realm.

The central library’s sudden closure left a ragged hole in Wellington life, but it has also offered residents the rare chance to wonder aloud at – and, importantly, to argue about – the possibilities for a future library. In particular, there has been fierce debate about the heritage value of the unsafe central library building, one of local architect Ian Athfield’s landmark projects designed in 1989. Some feel that the building should be demolished so a new 21st-century library can be raised in its place, while others wish to see the building retained and strengthened.

I’ve been asking myself whether I miss the library because it was simply a big library. But I’ve come to the conclusion that many of the things I miss are particular to the building… I miss being able to survey what everyone was doing as the escalator carried me up through the library’s light-filled centre. I miss the enormous glass facade that runs along the building’s southern side; the warmth and sunlight so freely accessible and joyful in a city where the houses are damp and cold. I miss eavesdropping on teenagers flirting at the next table over; it’s difficult to rendezvous under the cover of homework in the new libraries, which prioritise space-efficient single-sided counters and desks. And I miss the capaciousness of the building, and the ability to sink into a chair for hours without feeling scrutinised. In the temporary branches it feels like the modern stools and square-edged armchairs are intended to repel lingerers. This is not to say that Athfield’s building should necessarily be preserved, just that it’s vital to see a public space as more than its primary functions. It’s design details such as these – backed up by half a century of urbanism and placemaking research – that help shape the social life of these spaces.

It’s easy to feel melancholy about the current state of Wellington’s public realm. But I’m wary of misinterpreting these feelings of loss as nostalgia. It isn’t the past we should yearn for, but continual investment in developing and maintaining public spaces that accommodate diverse uses by a diverse range of residents. We need to advance a conception of the public realm that is contestable and evolving – coming to see this realm less for the spaces themselves and more for the human activity that they facilitate. The first step is coming to appreciate that the moments of social interaction we think of as incidental to our everyday lives are, in fact, the very stuff that knit us together.