Artist Ian Strange on concepts of home

For some, home is a way of mapping and understanding the world. Artist Ian Strange interrogates concepts of home through site-specific installations in suburban locations, challenging notions of memory, safety and security. OFFICE, as part of The Politics of Public Space lecture series, met the artist on Zoom in April of this year to discuss his work.

OFFICE

Hi Ian, thank you for finding the time to have a chat with us tonight. How are things over in Perth?

Ian Strange

Perth has gotten off lightly. It is the most isolated capital in the world—this is something I railed against as a teenager, but suddenly this is now an advantage in the pandemic. Western Australia is still locked off from other states, but they are slowly easing the movement restrictions, and everyone is cautiously stepping outside.

OYour career started in Perth as a graffiti artist. What was your relationship to the city? How did that progress to the suburbs and eventually the home?

ISAs a teenager getting into graffiti, I was always interested in art, but it was also about going out with groups of friends painting. Looking back, it still informs my practice—the idea of being sixteen, jumping fences and marking buildings. In many ways, that aesthetic of producing markings that don’t belong in places is still strong in my work.

The shift for me started after the move to New York. I was exhibiting primarily as a studio artist with a painting practice which came from working with aerosol. I was doing reasonably well as an artist, but was looking for ways of making art that felt more authentic to my experiences. I started reflecting on my adolescence, being a graffiti artist and growing up in the suburbs of Perth—it was almost the antithesis of living in New York. So I started making work that directly reacted to the spaces that I grew up in. This led to the project on Cockatoo Island in Sydney[1], which was a replica of my childhood home. At the time I thought of the work as a one-off, and it was primarily autobiographical. But the experience of making that led to making work in the States following the mortgage crisis, working with land banks and arts organisations in Detroit, Ohio, New York, New Jersey and New Hampshire. I began to build a body of work that dealt directly with houses, while also reacting to the icon of the American suburban home. That is where it started for me.

OAnd why the icon of the suburban home?

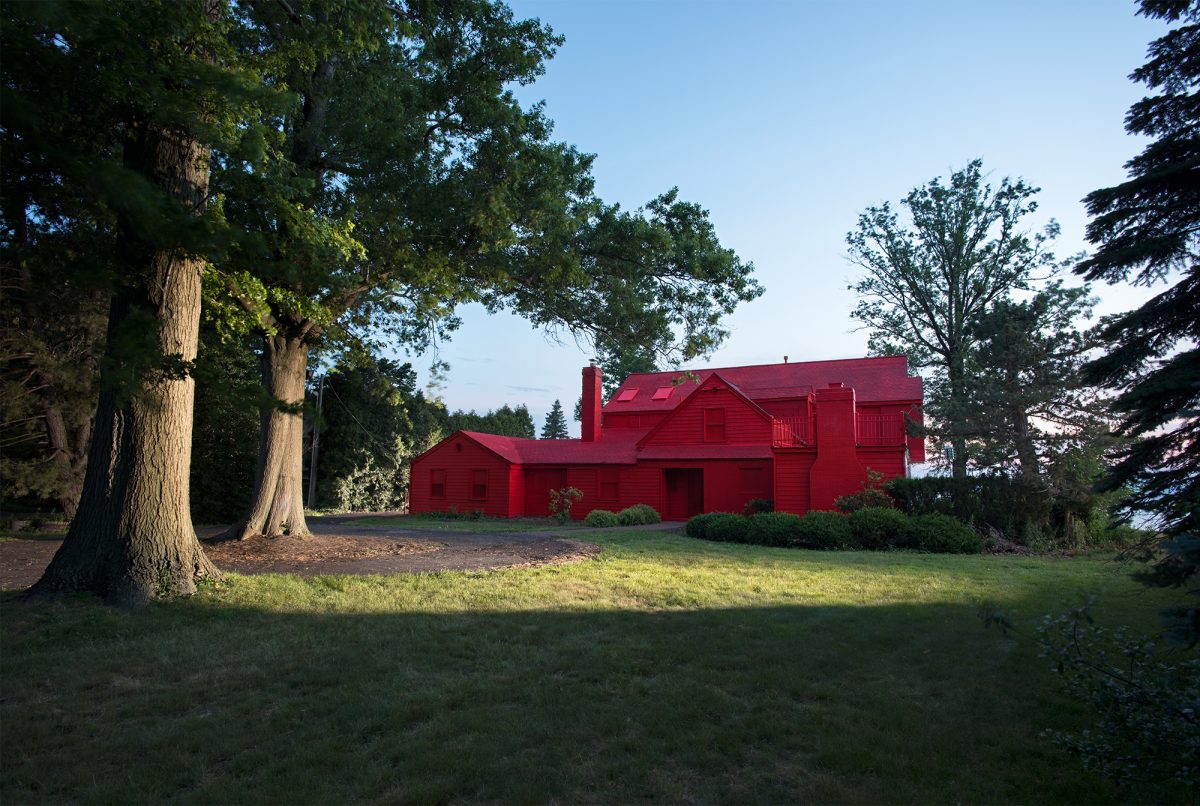

IS It’s shifting all the time. It started as an autobiographical work and then changed to being a consideration of the home as a poetic object: the home as an iconic, universal symbol and as a metaphor. As your first metaphor; you were born into a home, it creates a framework for understanding ideas of inside and outside—safety and security. People often dream of the same home all their lives, it becomes a way of mapping and understanding the world. That way an idea of home can be entrenched in people’s DNA. So I am interested in creating works directly onto the facades of homes as both an aesthetic and psychological act.

My most recent shift in thinking started while I was on-site with the communities. I began to see the process as central to understanding the project. Community consultation, collaboration, involving the site and its history began to inform the interventions and exhibitions. So over the last ten years, it has evolved from an autobiographical project, dissembling the image of the home, to then being more interested in the history of the site.

“… memory can be attached to an architecture, where it suddenly becomes an index of what happened inside it. The house then becomes greater than its material value.”

OWe understand you’re currently working on a permanent public sculpture in South Melbourne. What is the role of public art in the city? And your responsibility as an artist?

ISI like to connect into the history of the site. I like to think about the people who interact with it over time—I like to think about them as collaborators. There is space for a sculpture in a gallery, it can just sit there, but what I like about public art are the unexpected and ongoing interactions with the work. Maybe the general public isn’t expecting to engage with art, but these works often have a life of their own. Public sculptures can engage people in multiple ways and connect into a community.

The project in the City of Port Phillip is a collaboration with environmental scientists to understand water levels and flooding in the area. There is also a connection to the local historical society who are researching the history of flooding and industry. So it becomes an artifact, a casting of a piece of architecture which has many points of entry. It’s located next to a Primary School and has an integrated education program with the science and arts departments. I love the work. I could make another version of it, show it in a gallery and talk about it differently. It has multiple connection points to the site and its history because people are going to see it through their lives and have their own relationships with it.

Public works are difficult. You can’t be as didactic as a work made for a gallery: there are so many competing factors and interests in public projects. Sometimes, the bureaucracy is exhausting and can make me resent the work. The city’s legalities, forms and processes can be exhausting.

OWe can definitely sympathise with that feeling. Your work has often responded to crises, whether that’s the subprime mortgage crash in the United States or the earthquakes in New Zealand. How do you see your practice responding to this global crisis?

ISAt this stage, it is difficult to get a sense of it. A lot of my work is made in the aftermath of a crisis, as part of the recovery. Sometimes you can see a situation and understand how art can be part of the conversation—to contribute, and how a work can be made in that space. At the moment, we don’t understand the full scope of this pandemic. Other than how working from home is shifting people’s relationship to domestic space and their jobs. That is all I can think about at the moment, but I’m sure it’s going to inform my practice. I’ve got a monograph coming out and we have decided to slow down production to write this into the work.

OYou mentioned earlier your involvement with land banks in the United States after the Global Financial Crisis, can you explain what the land bank is? What effect they had on the suburbs?

ISI’m not a complete expert on it, and the structures of land banks change from city to city. But following the GFC, if a home is foreclosed on or abandoned or left or there are overdue city taxes, the house will eventually fall into the domain of the city. The city sets up an organisation, which is the land bank and their remit is to figure out what to do with these houses. A large part of it, particularly after the GFC in cities like Detroit and Ohio, was to demolish houses where they could afford it. They also rehabilitate the housing and stabilise the houses — once the snow gets in the bones of these timber-framed buildings, they’re not salvageable. When you see houses online for $100 or $200, a land bank is generally selling it with the condition of an $80,000 or $90,000 commitment of investment to restore the house. Land banks bring people back into communities, and many land banks have an arts wing or collaborate with artists on houses that are set to be demolished.

These initiatives are restricting predatory buying—people buying up houses and not doing anything with them. Land banks ensure houses are given to owners who will rehabilitate, avoiding blank investments and as consequence leaving blighted houses in the community.

Their demolition timelines can be controversial. Many neighbourhoods don’t want these blighted houses in their street and try to move them up the demolition line. Our work makes these houses look better, and the neighbours are so happy because it means that it has to be demolished sooner.

OHave you found a difference in attitude towards suburban lifestyles in Australia, the United States and New Zealand?

ISWhat I find interesting is that they all share a similar idea of inclusive homeownership. It is important to mention that these suburbs are exclusively for white people, a policy that was replicated throughout Australia and the United States. There is a long history of excluding people from homeownership. The idea of all-white suburbs and the romantic notion of suburbia was replicated after the war in both countries in similar ways. There is a broader middle class in Australia than the United States, which has meant that homeownership has traditionally been larger. Until recently, there has been uninterrupted economic growth in Australia, which has given the housing sector some stability. The home in Australia is a far more loaded image and symbol of economic stability than it has been in the United States.

OYou’ve also been documenting the phenomenon of ‘holdout homes’ which are symbolic in a different way. Can you explain what they are, and your interest in them?

ISI have been interested in the concept of the holdout home or the nail house for a long time; similar to the film The Castle or the house at the beginning of the film UP. There is a romantic notion of the little old lady or the single dogged homeowner holding out against developers. But it extends right through to people refusing to leave their homes in Fukushima, Chernobyl, and nail houses in China that are challenging ideas of private ownership. This idea that people with such a strong emotional connection to a piece of architecture are willing to fight to stay there even when it is unsafe is fascinating. The idea that memory can be attached to an architecture, where it suddenly becomes an index of what happened inside it. The house then becomes greater than its material value. So these more extreme cases of people not willing to leave their homes reveal a kind of common human truth about our relationship to architecture.

OYou have focused on houses as symbols or icons. Have you ever considered a work addressing apartments and what home means in high-rise contexts?

ISThe symbol of the home, the square with the triangle on top, is interesting because it is a repetitive form that is so ingrained in people; it can be specific to an area and also act as a symbol for the idea of home. I like working with houses and those forms because they are so repetitive and familiar. Although apartment buildings are repetitive, I don’t think my interventions would have the same power. I understand there are different attitudes to home, a lot of people don’t grow up in a house that resembles a child’s drawing, but it is that image of the archetypal home that is both a home and a symbol of home.

OHas this crisis changed your perspective on home?

ISA lot of people are posting my work online: a lot of my older projects, in particular, a body of work called Island[2], which looked at the home as a desert island, a place of entrapment but also a place of safety. Island appears to be resonating with people during this period of isolation at home in a way I couldn’t have predicted. This period will shift how people think about the home, but it also reveals the existing wealth divide and how far we have strayed from this post-war idea of universal homeownership.

This interview is an abridged version. The full version is published in The Politics of Public Space, Volume Two — a quarterly publication of transcripts that speak directly to the city and the way we read it – alongside interviews with Myria Georgiou, Saskia Sassen, Jack Self, Brooke Holmes and Alfredo Brillembourg. This publication was produced by OFFICE — a multidisciplinary design & research practice based out of Melbourne. As a registered charity OFFICE is legally bound to a constitution that controls the operation and output of the studio. This alternative mode of practice questions specifically architects and landscape architects current relationship to the built environment. To purchase the book please visit their website.