Artist Ruth Buchanan on living life collectively at R50 in Berlin

As Oscar Wilde wrote in his 1889 essay ‘The Decay of Lying’, “life imitates art far more than art imitates life”. When the boundaries are blurred between art and living, can alternative ways of life thrive? Our editor Sophie Rzepecky spoke to Ruth Buchanan, a Berlin-based artist originally from Aotearoa New Zealand, during the recent lockdowns to chat about her work and collective living at Ritterstraße 50.

We sit across from one another, worlds apart, yet beamed into each other’s intimate spaces (my bedroom; her artist studio). On the screen, Ruth Buchanan tells me that her life had always been quite migratory until she moved into Ritterstraße 50 (also known in architectural circles as ‘R50’) in 2013 – a collectively funded building with a focus on communal living in the neighbourhood of Kreuzberg in Berlin. Moving to the Netherlands to pursue a Masters in the late 2000s at the Piet Zwart Institute in Rotterdam, she had lived in subsidised housing known in Dutch as ‘Antikraak’ (‘anti-squatting’), a form of vacant real estate where residents guard houses from prospective squatters. During her residency at the Jan Van Eyck Academy in Maastricht, she lived in her studio for a while, and eventually a dilapidated 19th-century farmhouse with a group of artists. Through these experiences, ideals of the collective and the commons intertwined with her work and life. Her current home at R50 has given her the space to grow her young family alongside her artistic practice: “I realised that this apartment is the longest I’ve lived anywhere in my entire life, and it plays a big part in how I express myself.”

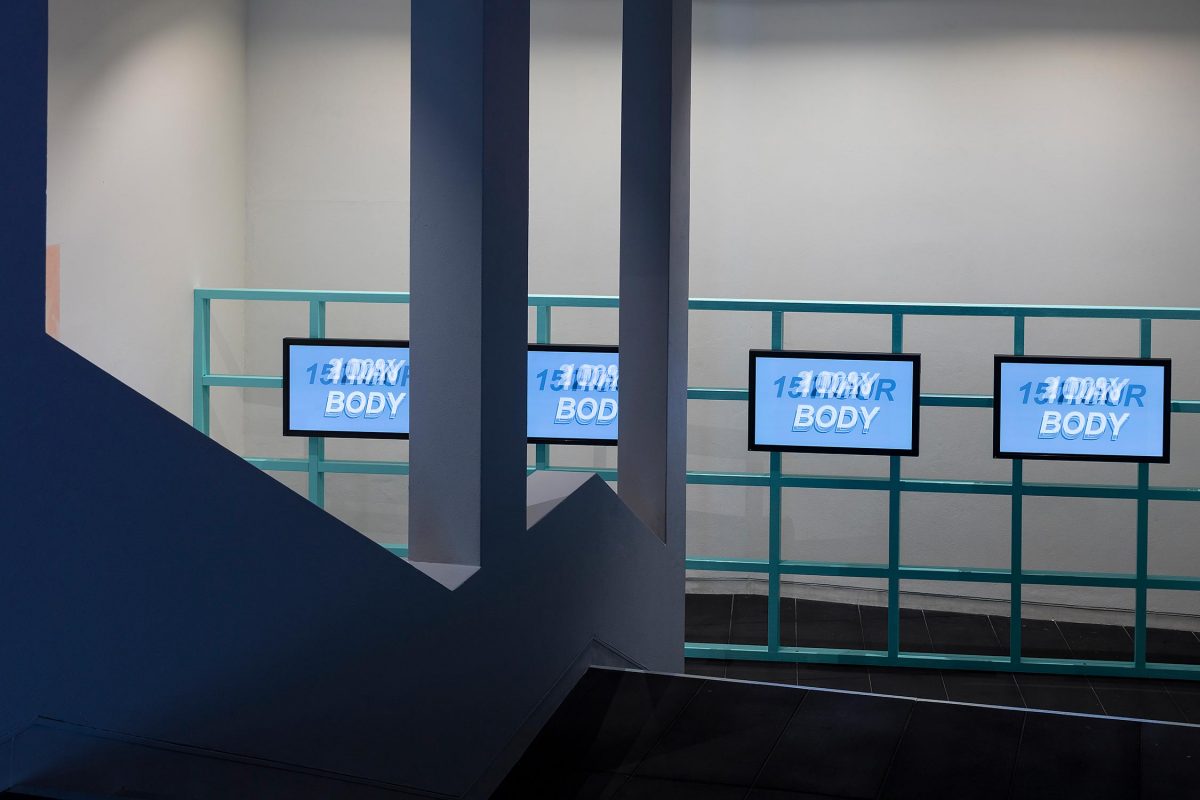

Over the years, Buchanan’s multidisciplinary work has developed to explore the relationship between body, power, archive and language through research-like projects which use architectural and design elements of everyday life – room dividers, curtains, carpets and scaffolding – to critique the movement of bodies through space. Who gets to decide where we go and how we get there? Who gets to decide what histories we read, and how we read them? Her work has always travelled between Aotearoa New Zealand and the European context. The exhibition BAD VISUAL SYSTEMS (2016) at Adam Art Gallery Te Pātaka Toi in Wellington blurred the role of the artist, designer and curator to critique methods of display, and won her the 2018 Walters Prize. The scene in which I find myself / Or, where does my body belong (2019–20), a recent solo exhibition at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery in Ngāmotu New Plymouth, saw her dissect the gallery’s 50-year-old collection to reveal inequalities and imbalances (75% of the collection is represented by white male artists), problematising these disparities through working with categories used to organise our identities. Her apartment is, in a way, an extension of these ways of thinking: “I test a lot in here in terms of materials and structures. When exhibitions are finished, we often end up with a lot of my work inside. The apartment has almost become an extension of living in and with art.”

Love brought her to Berlin in early 2010. Buchanan’s partner had been living there since 1990, studying architecture and witnessing the city in transformation after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Feelings of liberation and freedom were revolutionising the architectural schooling system, with students throwing off the more traditional model of ‘master and student’ and strict disciplines. They defined their own curriculum, bringing architects and artists together in dialogue. There was a feeling that power structures could be rewritten, and that the city was redefining its identity. Berlin was reckoning with its past in the aftermath of World War Two and the city’s divide between the East German Republic (the GDR, also known as East Germany) and the West. “The longer I live in Berlin, the more I realise there is a lot of societal disfunction which has not been addressed,” Buchanan says. “But when I moved, it almost felt like a blank slate. I was interested in how the city’s recent history was manifested in its architecture and psyche.”

In 2010 architects ifau und Jesko Fezer and Heide & von Beckerath brought together a group of 32 likeminded people to collaborate with them on R50, Buchanan and her partner included. The land that the building sits upon was one of many gaps in the city left after WW2 and the reunification of East and West Berlin. It had been rezoned multiple times – as a kindergarten and an access road – but finally the Berlin Senate, the body governing the city state, ran a limited competition for housing on the site. The proposal for R50, a Baugruppe (‘building group’) with a focus on collectivity and affordability, won the pitch to build in 2011. “Our case is specifically interesting, because there was no divide between the client and the commissioner,” mentions Buchanan. “Some of the architects also moved into the building, so in a way they were self-commissioning.” The unusual planning and development process gave it an edge; “Our building had a focus on affordability for the residents and was developed with a participatory design process. More and more people are interested in Baugruppe, but those aspects of participatory or discursive design are not automatic if you use it as a legal structure. There are a lot of Baugruppe in Berlin that are just luxury apartments.” The collaborative process was mediated by the architects in the planning phase of the building. “We were making collective decisions about things like bathroom tiles, seemingly small details which actually revealed life priorities and vulnerabilities, limits and desires. We were simultaneously trying to figure out what each decision meant as a family or individually and as a collective, in a very public and open way. It didn’t come naturally for everyone.”

One strength of the collective process was that everyone came to the table with different skills and life experience; some struggled to read a floorplan but could contribute in other ways. A crucial conversation was on the distribution of cost and financial burden. The residents voted to collectively own the balcony façade of the building as well as the laundry, communal meeting room, roof terrace, elevator and ground-floor garden. As Buchanan puts it, this “made those spaces everybody’s spaces” and consequently all the residents are responsible for taking care of them. Sure, conflicts arose along the way – “People had different understandings of what the primary purpose of particular zones in the building were. How collective do those shared spaces need to be ?” – but, ultimately, such disagreements made the community stronger. Over time, the building and its residents settled. “Now the ecosystem’s established and running smoothly. There are still moments where we have to make decisions together, but we understand how to do this constructively.”

Seven years later, some residents interact more than others with communal spaces, which have become a natural extension of living space. The relationships to the communal spaces change and evolve as the community has grown up; as Buchanan puts it, “The different parts of the building have different life cycles.” Teenagers, who moved into R50 as children and once played happily in the garden, are now more likely to use the roof terrace for parties. But what of the next 50 years or so? “Sometimes I joke that the common room will have to become the apartment for live-in carers. All of the people who live in the building are going to get old at the same time.” Jokes aside, the building is well set up for an aging population, with an elevator, ramps and adaptable communal spaces.

Despite the Covid-19 pandemic, R50 weathered the lockdown well. “I’m not in my neighbour’s face all the time, but I have never felt totally alone or isolated. The building has become a space of empathy, everyone is keeping safe but also connecting.” The relationships that Buchanan has built over the seven years of living in the building are resilient. She is close to contemporary artist and fellow resident Judith Hopf, whose sculptural work uses materials found in everyday life, such as building bricks, to critique contemporary culture. They have collaborated over the years, both materially and through dialogue. “In a slow-burn kind of way, living in R50 has impacted on my self-understanding and worldview. Having the capacity to engage with a space over a long period of time and transform it, alongside my relationships within the building, especially with Judith, have been immeasurably valuable.” Suited to lockdown, her current work is publishing-focused, with research centred on the Aotearoa New Zealand poet JC Sturm (also known as Te Kare Papuni). “I do feel like her work is something that is useful to look at now,” Buchanan says. “It lays bare a dichotomy between the weak and the strong, and how we’re always both things, somehow. Her poems are useful ways of thinking through the human condition.”

The pandemic has brought to the surface many underlying inequalities for so many people, while exaggerating geographic distance. For Buchanan, home will always be Aotearoa, and it beckons from afar; yet, living in a collective during a moment of uncertainty or crisis has emotional benefits. “I hope people can become open to this kind of porous community. Yes, an anonymous apartment block is challenging, but if it has shared zones, and there is the capacity for it to be intergenerational, it could be so positive.” In places like Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland where there is a dire housing crisis, the benefits of medium-density housing could become a valued part of the urban landscape and create more empathetic living environments for the elderly or vulnerable. Perhaps the pandemic can also be a moment of reflection for some. “I hope that this is going to be an opportunity for people to really look at how they want to lead their lives.”