Christopher Hawthorne is tackling housing and affordability in L.A.

Chicago has the Chicago Architecture Center, New York has the Municipal Art Society, and Melbourne has countless public and non-profit institutions such as Open House, MPavilion and the National Gallery of Victoria to raise awareness and public literacy around design in our built environment. However, says Christopher Hawthorne, “There is no city that needs that conversation more than LA, and there is no city that has fewer of these institutions and platforms than LA.”

As Los Angeles enters a new phase of intensification described as ‘post suburbia’, design leadership is as critical as ever. With a once-in-a-generation opportunity for significant public investment, the progressive Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti sought out not a seasoned bureaucrat, but a public commentator. Enter Christopher Hawthorne: the lead architecture critic for the Los Angeles Times from 2004 to 2018, joining the City of Los Angeles as the chief design officer.

The creation of this new type of advocate speaks to the politics of the built environment in Los Angeles, a city with a history of strong union representation, cowboy developers, and NIMBY and tenant organisations. What the mayor saw in the critic was a track record of engaging with a broad spectrum of the community outside of the design industry, but also a passion for generating public conversations, rather than technocratic solutions.

Los Angeles is a city under significant stress: climate risk through urban heat effects, fire, and sea-level rise; and lack of equity of access to housing and transit, employment and services. Christopher describes this as the failure of the 1967 image of the ‘second’ Los Angeles, which had replaced the early 1900s tram-driven urban expansion with a laissez-faire city of cheap fuel, subsidised highways, and single-family houses within a short drive of manufacturing jobs. “1967 was the golden age of second Los Angeles, when it did work for a broad cross-section. The freeways were broad enough that you could get from any point to any other point within half an hour. A working-class family could buy a house. You could come to LA as an immigrant family and you could buy your way into that suburbanised dream.”

Los Angeles invented that combination of suburban amenity within a metropolitan scale, Christopher points out. “It was a radical and in many ways successful experiment, but it began to run its course by the ’80s and ’90s”. By then, tensions flared in significant civil unrest, teamed with industrial decline and economic shock, and the dream began to fail those who couldn’t buy their way out of difficulty. Los Angeles during this period is said to have lost its economic ‘middle’, leaving instead a polarised city with the ultra-elite in the knowledge and entertainment economy, and a supporting casualised workforce, heavily dependent on exploitative migrant labour.

Los Angeles parallels the transition of many American cities, which entered a regeneration cycle after 50 years of hollowing out caused by government policies that incentivised ‘white flight’ to the suburbs and concentrated more vulnerable and ethnically diverse populations in areas flanking downtown business districts. However, where in many cities urban regeneration has been driven from the top down by the state, the impetus for the current ‘third phase’ of Los Angeles development has come from the citizens themselves.

“The voters told us before the policymakers had articulated it,” Christopher says. “In 2008, we had the most important moment in the emergence of the third LA: a transit tax measure on the ballot in LA County, that asked if voters wanted to raise the sale tax by half a penny for 30 years, which required a supermajority (two-thirds vote).” Against the expectations of commentators, the frustration with congestion converted to a 67 percent ‘yes’ vote, sufficient to achieve the supermajority required. (The tax measure was extended in 2016 with an increased majority.) This nominal sales tax, projected into the medium-to-long term, enabled a dependable method to fund major infrastructure, amounting to $200 billion over two generations.

However, as long as the built environment is car- and parking-centric, public transport ridership will remain low, with limited impacts on the quality of life and carbon footprint of the city. With the 2028 Olympics looming, how can a design-led conversation refocus efforts from a transit-only approach towards the total design of the urban environment?

As a writer and a critic with a broad understanding of the city outside of the traditional conception of ‘architecture’, Christopher is deeply interested in the questions this new phase of regeneration poses for Los Angeles identity, one of the world’s most photographed and self-conscious cities: “Is there an LA sensibility and what does that mean? It’s a more complicated or different question in LA, because of our history of reinvention and not looking to the past, and being the centre of Hollywood production of simulacra, unreal cities. The question of authenticity is different and much more shaded in LA.”

Christopher is adamant that post-suburban Los Angeles doesn’t need to shed the best aspects of its 1960s’ identity for a generic global model of urban regeneration. This is where Christopher is to focus his efforts, with a portfolio of small and large public realm initiatives, along with a design-led approach to infill residential development, and the procurement of design excellence in public works. Through the establishment of a ‘Committee on Memory’ with artists and key thinkers in the industry, he hopes to explore urban issues within an authentic, place-based conceptual framework.

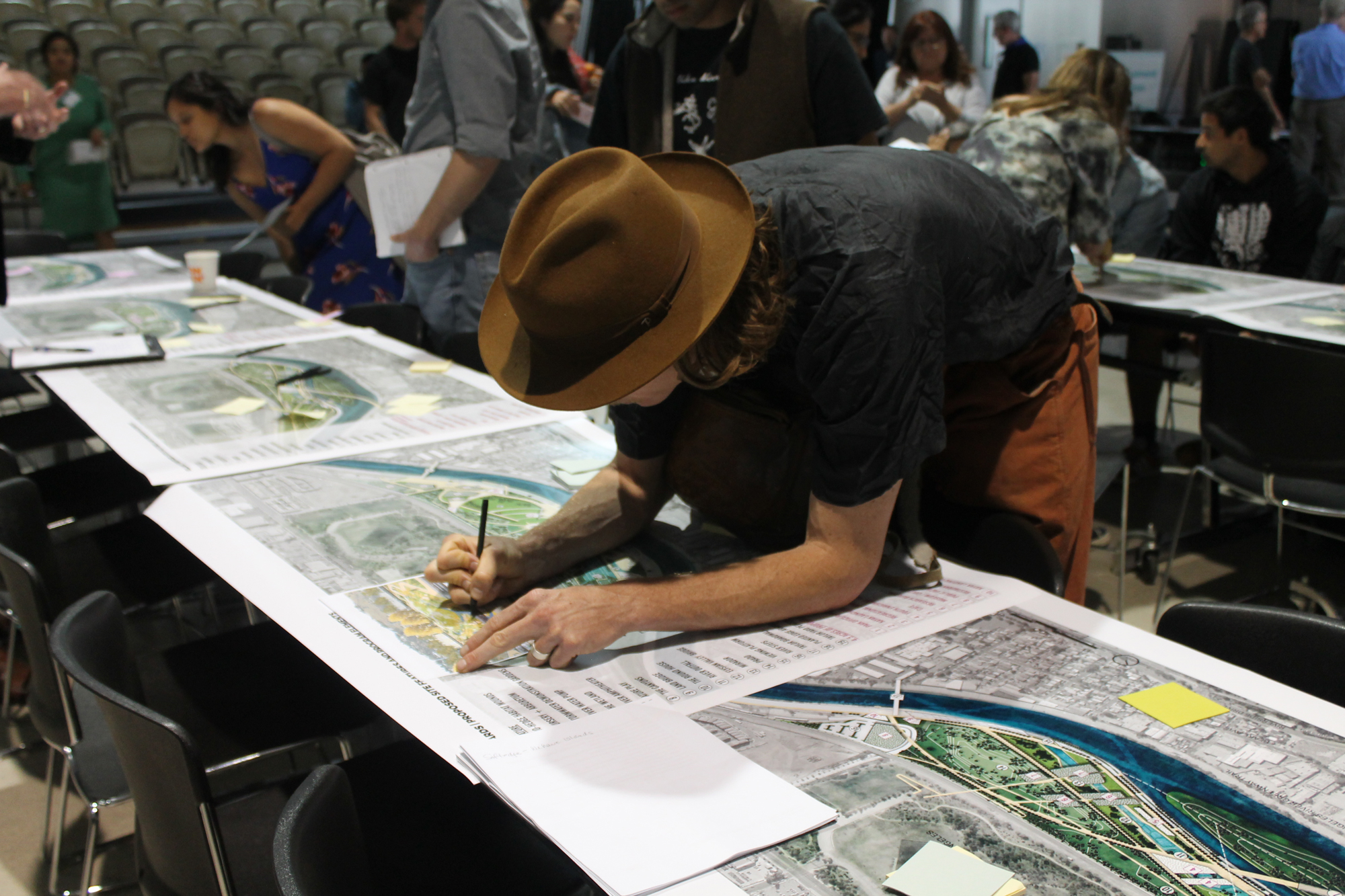

A specific catalyst project is sited along the infamous Los Angeles River. The 80-kilometre-long concrete culvert was once the lifeblood of the region, connecting mountains to the ocean for its First Nations people, before becoming the scene of countless Hollywood crime and car chase shoots. The conversion of a former riverside industrial site, Taylor Yard G2, as part of a larger contiguous public space either side of the river, now provides an opportunity to reconnect Angelenos to their invisible river landscape. As a basis for public discussion, three distinct design concepts are being developed; meanwhile, Christopher has commissioned a temporary viewing platform from which the public can oversee the long construction phase.

Another example is Los Angeles’s ‘right of way’ project, a city-wide attempt to reconfigure the design of major streets through a systematic ‘kit of parts’ approach, to incorporate shade trees, more generous pedestrian space, a reduction in space for private vehicles, and high-quality lighting and street furniture. Given the extensive distribution of these neglected arterial roads, this offers an immense opportunity to have a large-scale impact on the pedestrian environment as well as contributing to urban cooling (in a city where 80 percent of the tree canopy grows where 1 percent lives). With a complex web of siloed departments variously responsible for lighting, bus shelters, road surface, footpaths and shopfront awnings, Christopher is required to engage in organisational redesign as much as spatial; he is charged with bringing together a framework to bind diverse stakeholders into a singular coherent vision. In an attempt to open the process up, the lighting fixtures and street furniture will be tendered through a competition process, and supported with media to engage a broader audience beyond City Hall.

The magnitude of Christopher’s challenge is formidable, given the scale of the City of Los Angeles jurisdiction: an area of 1,300km2 and a population of near to 4 million, nested within the larger metropolitan area of the County of Los Angeles with a population of around 10 million. (Comparatively, the City of Melbourne has a population of 140,000 and an area of 36km2.) This gives significantly more design opportunity, but brings with it the significant question of the ‘economy of effort’. How can design energy be invested in prototypes that remain place-specific, while having the maximum impact on the infrastructure of the city at large?

Perhaps the most political project that Christopher hopes to tackle is housing supply and affordability. Owing to decades-old zoning restrictions, a significant proportion of the city is restricted to single-family dwellings. Very limited growth in new dwelling stock (only 80,000 dwellings a year, well short of the 3.5 million required by 2025), teamed with high demand and associated prices, is resulting in displacement of lower-income residents. According to the National Association of Home Builders, 92 percent of Los Angeles homes are now considered unaffordable to median-income earners. Senate Bill 50 in the State of California aims to address this shortfall through an upzoning across the state, which would increase allowed building heights and densities across all metropolitan areas. While seemingly sensible, this top-down-fits-all approach has been challenged on many fronts: researchers argue that restrictive setback requirements imposed by municipalities will prevent density increases, while tenant and NIMBY groups have rallied together as strange bedfellows, in favour of preserving rent-protected properties and high-value single-family areas.

In a city without any noteworthy legacy of public housing construction, Los Angeles is heavily reliant on private rental protection measures to preserve low-income homes. Protection applies to properties older than 1995, many of which are low-rise duplexes, townhouses or low-rise apartments. The fear of eviction cannot be dismissed. In the three months prior to July 2019, applications were filed to remove rent control from 657 apartments, with owners buoyed by rising land value and the possibility of sale on the open market for luxury redevelopment. Increasing the development potential on these properties immediately heightens the pressure on protected tenants. The Bill aims to protect these areas through exempting properties that are or have been recently rented, though activists argue this doesn’t go far enough.

While Christopher supports the Bill, he sees the opportunity to introduce more palatable forms of infill density, such as two to four dwellings on a single-family site, which can be planned in partnership with local communities. He is working closely with planners on regulatory changes, as well as a ‘missing middle’ design competition (similar to recent examples in Queensland and NSW), with the opportunity to follow up with the creation of a series of small catalyst projects. Rather than abandoning Los Angeles’s character, Christopher suggests that this model of infill can draw upon the “modest medium-density housing of Irving Gill’s Santa Barbara Horatio Court terrace homes of 1919 or Koning Eizenberg’s Hollywood Duplex of 1988.”

One year into the job, consistent throughout Christopher’s emerging portfolio is the desire to “look first within our own backyard”, rather than importing fashionable concepts from abroad. Far from the ‘city architect’ in the Robert Moses mold, Christopher’s is a more nuanced role, focused both on embedding design processes in public office, as well as generating broader public discourse. His background as a public critic, with a remarkable depth of knowledge about Los Angeles’s social and political history, brings a degree of sensitivity and awareness to the role. In a city where ‘good design’ can be viewed with suspicion as a tool for displacement, this sensitivity is critical. Christopher’s challenge is to buck the trend of many North American cities, where good design is a luxury for largely white, gentrified, higher-income urban neighbourhoods, and instead generate a public belief in the value of design for all Angelenos. He says, “One of the things that makes this moment unusual is that we are remaking the public spaces and the infrastructure of the city in fundamental ways.”

For those who want to follow the rabbit hole further, Andy encourages you to watch Los Angeles Plays Itself (2003) Thom Andersen, read ‘Los Angeles, The Architecture of Four Ecologies’, and ‘The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.

A warm thank you to Christopher for chatting with us after his lecture at the Living Cities Forum, and to Andy for crafting this insightful piece. Andy is an urban designer and design advocate, passionate about helping government, ethical developers and communities create successful places. Find out more about Andy here. This article also appears in our print issue #12: (Future) Legacies.