Šejla Kamerić on art as resistance

Šejla Kamerić’s artistic practice is bold, political and deeply personal. She questions humanity’s destructive behaviour and sees art as an act of resistance. Ennis Ćehić spent time getting to know Šejla, understanding her artistic practice, what it means to be a survivor of war and the role of women’s rights, identity and sustainability in her work.

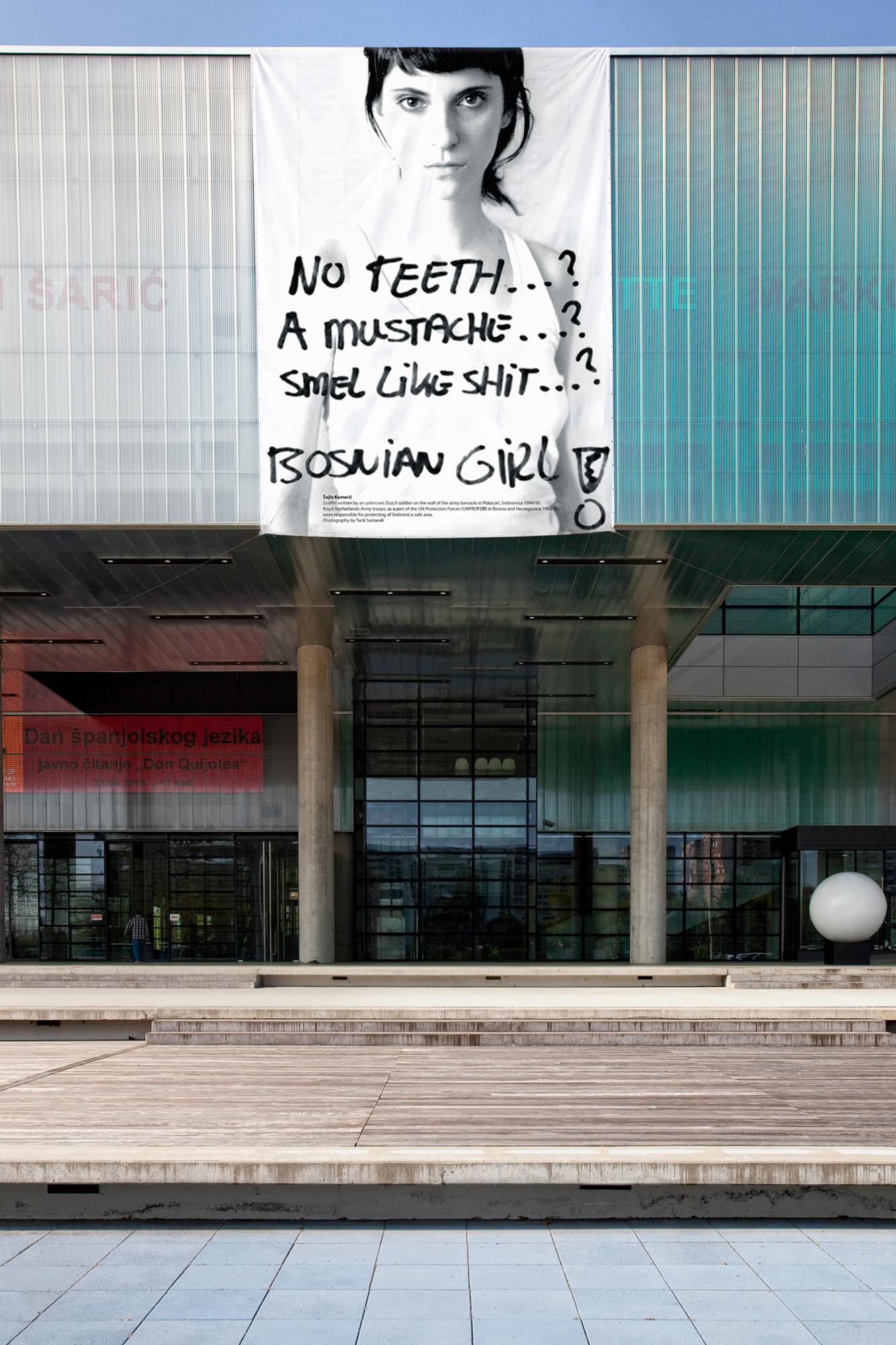

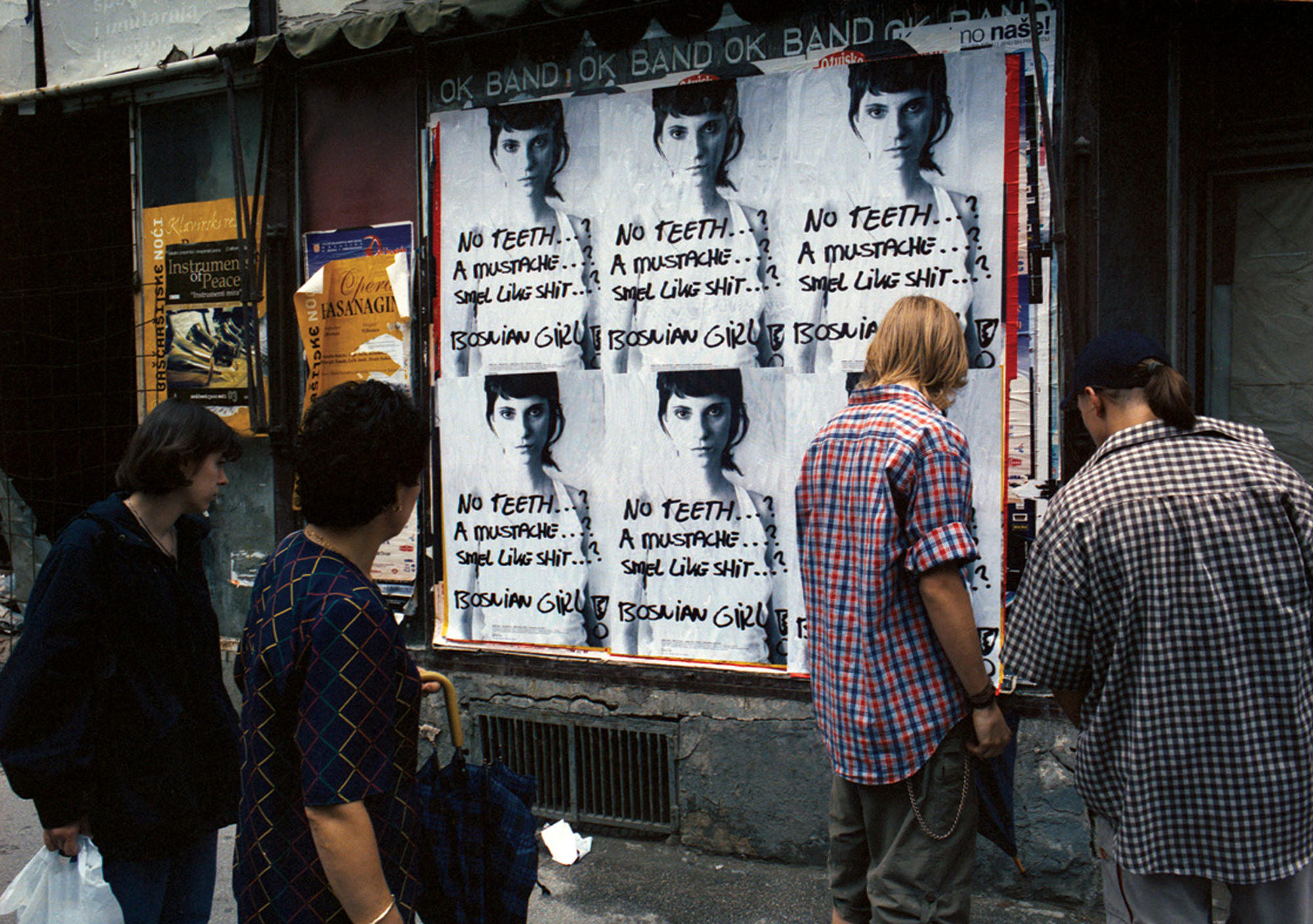

‘No teeth…? A mustache…? Smell like shit…? Bosnian Girl!’

These words are inscribed on a black-and-white fashion photograph of a young, dark-haired woman inside the Museum of Contemporary Art (MSU) in Zagreb. From its prime position on the ground floor, measuring approximately six meters in height, the image constantly reappears to visitors across the multiple levels of the museum. The brutal, unavoidable directness of the words scrawled over the young woman seeks to be memorized: an open wound, seared into our collective memory of a moment from Bosnia & Herzegovina’s history, not to be forgotten.

The scrawl was written by an unknown Dutch soldier on the walls of the military barracks in Potočari, Srebrenica in 1995, alongside many other pieces of crude graffiti. In July of that year, the United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), to which the soldier belonged, failed to protect the designated ‘safe zone’ of Potočari, leading it to be overrun by the Serb army of Republika Srpska, who then systematically massacred over 8,000 of the town’s Muslim men and boys. This failure led to the worst European genocide since WWII – and this poster became a visual reminder of the tragedy.

Bosnian Girl, as the artwork became known, is the work of artist Šejla Kamerić.

Devised as a street poster campaign, it first appeared splattered across the streets of her hometown Sarajevo in 2003 – a year before The Hague officially ruled the massacre in Srebrenica a genocide. Its bold aesthetic, political directness and simplicity made Bosnian Girl an instant icon of the Balkans, while simultaneously catapulting Šejla into international stardom. Today, Šejla lives and works between Sarajevo, Berlin and the coastal Croatian region of Istria. She exhibits widely across the world and her works are in permanent collections of Tate Modern, Musée d’Art Moderne de la ville de Paris, MACBA in Barcelona, and preeminent museums across Europe, from Rotterdam across Vienna to Istanbul.

In approaching to interview Šejla, I realised that I had always considered Bosnia & Herzegovina to be a land of poets, writers and musicians – the Nobel Prize winner Ivo Andrić, his contemporary Meša Selimović, or the composer and musician Goran Bregović. The umjetniks i.e. artists of the country hadn’t had the same recognition. But with Bosnian Girl and her wider array of works, including EU/Others (2000), Basics (2001), 1395 Days without Red (2010), Šejla has become an exception – Bosnia & Herzegovina’s foremost contemporary artist.

With a career now spanning close to twenty years, and encompassing film, installation, photographs and drawings, Šejla’s work bears a signature simplicity and a politically motivated resolve. But outside of the war-bound motifs – Sarajevo, identity, women’s rights – her work also deals with the subject of sustainability. In 2011, Red Carpet, a handmade rug woven out of second-hand clothes, was her first foray into investigating fashion waste. Similarly, BFF (2015) an over-sized teddy bear was an installation made of second-hand fur, leather, fabric, plastic bottles and clothes. And it’s this work precisely that I became interested in when I first met Šejla in Sarajevo this year. Why did she turn towards fashion waste, and exploitation in the fashion industry?

“I see fashion waste as a symbol of the destructive society we live in,” she tells me over a cup of tea at Blind Tiger, a popular bar in central Sarajevo. “We produce goods that we do not need and, in that process, we abuse and destroy the earth. We destroy and pollute our environment; we harm ourselves.”

The question of humanity’s destructive behaviour fascinates Šejla. And it makes sense why: she’s a survivor of the war, and her ongoing exploration of human obliteration connects her to her own past. “Wars are just one part of a destructive system rooted in exploitation,” she adds. Everyday fashion is certainly part of that. For years, she has focused on the position of women in the fashion industry, where exploitation in production processes, marketing and sales relies on a false idea that fashion is something we need and have to keep investing in. “Nowadays, I’m very much interested in the idea of making art by upcycling materials, or being as little environmentally harmful as possible.”

Red Carpet took the form of a rag-rug made entirely out of red coloured second-hand clothes. All parts of clothing were left visible, with zippers, buttons, sleeves, socks and tags clearly identifiable. With this kind of sedimentary layering of worn clothes, a collective narrative was stitched together, each piece of clothing carrying its own story and representing real human beings— an epitome of a collective experience.

“When I was making this piece, and was in process of collecting the clothes, I realised that 99% of the second-hand clothing you buy in Bosnia is imported from the West. The Balkans and the eastern European region is the first depository step of thrown-away clothing—the leftovers of the fashion world, the garbage collection, so to speak.”

There’s a deliberate, almost premeditated act of opposition present in Šejla’s work. It actively resists. Whether it’s political propaganda, erasure of history, cultural stigma, patriarchy or like of late, the fashion and corporate industries—Šejla fights fiercely and without reserve. This politically-motivated universality is one of the reasons why her work feels so relevant, so necessary. “Art is an act of resistance”, she tells me. “Art is a challenge and it has to impose challenges. It also has to preserve integrity in such a way to be critical to society. That is its stake in society.”

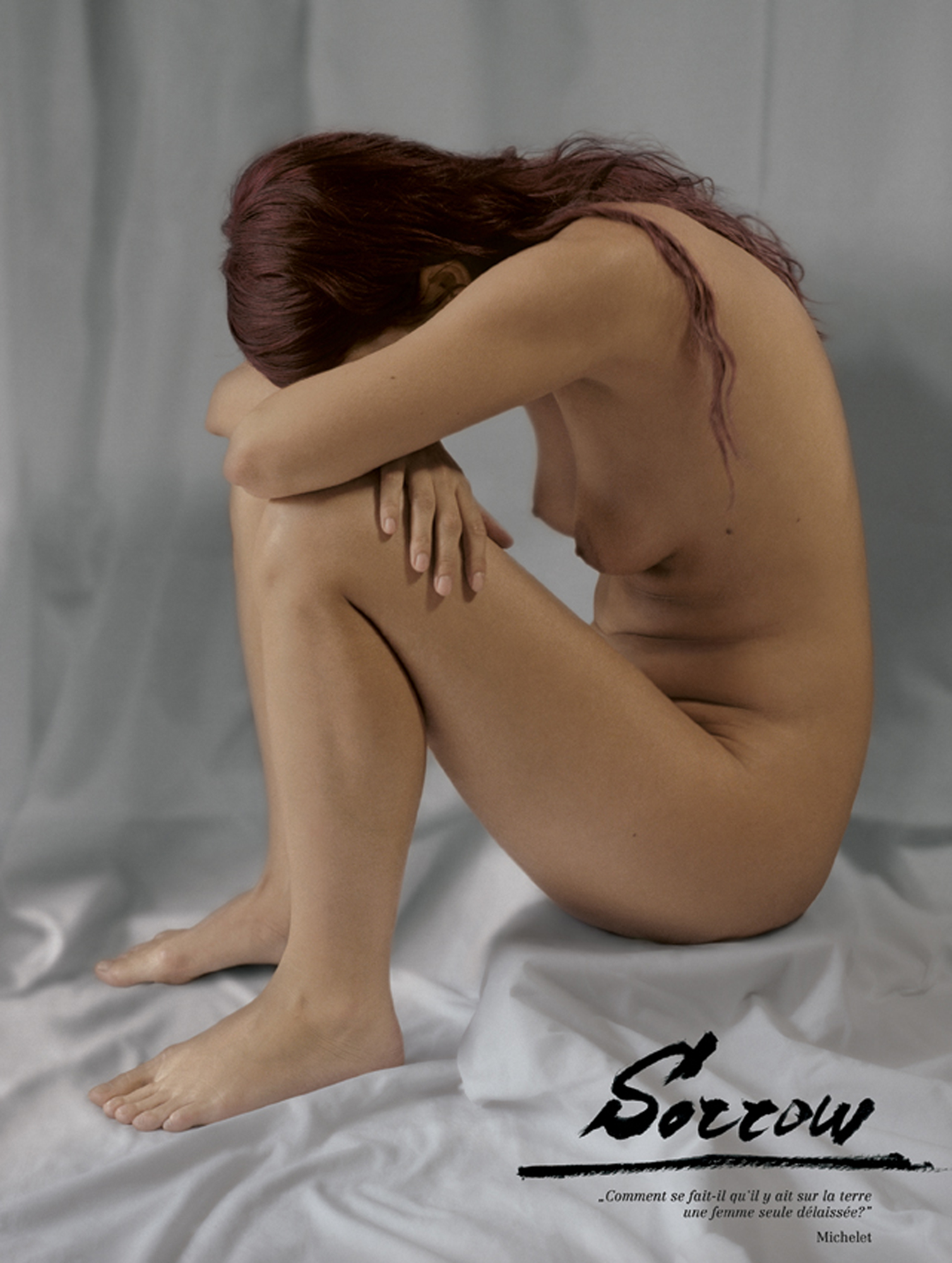

Šejla lived through the four-year Siege of Sarajevo that lasted from 1991-1995. This, she tells me, made her realise that everything is political. “I do not have the privilege to imagine being ‘apolitical’.” This experience is best captured in the award-winning film 1395 Days Without Red she created in 2010 in collaboration with Anri Sala and Ari Benjamin Meyers. And yet, she refused to let the experience of war define her sensibility as an artist, as a person. In 2005, following the international success of Bosnian Girl, a friend found a book on Vincent van Gogh during a visit to Šejla’s studio in Sarajevo. The book told the story of Sien—the woman who Van Gogh brought to live with and used as a model, famously sketched in the work Sorrow. The subtitle of the work, written in English, ‘how can there be lonely, deserted women in the world?’ had engrossed Šejla in her student days. “That was the moment of reconnection with myself from ‘before the war’. The brutality of the war makes you think that nothing before the war was real and nothing can exist after. Once you survive war, this notion is something you have to fight against. Sorrow helped me understand who I was before, who I am, and what I stand for. It made me realise that my compassion and beliefs would exist even without the terror I survived.” This chance encounter led her to re-make the work as a photograph, with herself as the model.

Following Sorrow, Šejla’s work became more feminist and political in nature. “I needed to mature as a woman and an artist to fully understand what kind of feminist I am and how feminist my works are. Feminism is so important to me, but for a long period of my young age I harboured a strong, silent resentment to it. I did not want to be labelled, so I did not declare myself one. I fought against all identities. I resisted being labelled a ‘Bosnian girl’, I resisted being labelled a ‘woman,’ – because what exactly does nationality mean and what exactly does my gender mean?

“I hope that we reached the point of understanding that there is not one single form of feminism, but that many forms of feminism do hold one thing in common: the belief that all humans should be equal. Unfortunately, I see minimal progress when it comes to men understanding their roll in feminism, and accepting their responsibility in the society we live in. We all have a long way ahead of us. It will take a long time to overcome centuries of oppression.”

In 2000, three years before Bosnian Girl captivated the European art world, Šejla created EU/Others for the European Biennale for Contemporary Art in Ljubljana, which was themed “Borderline Syndrome.” EU/Others became an intervention over the three bridges of Josef Plečnik, connecting the Prešernov Square with the old city centre. On each bridge, she mounted overhead notices of the kind seen at airports and border checkpoints, separating EU citizens from “others”. In this case, however, each notice has the word “EU-CITIZENS” on one side and “OTHERS” on the reverse, so that you step onto a bridge as an EU citizen but have to leave it as an “other”.

In context of the current Brexit crisis, the work appears to question imposed national identities and state borders – even though it was made nineteen years ago, in a vastly different political context. The European Union was fairly a new creation, borders in Europe freshly changed, the fall of the Eastern Block as recent as the Balkan wars and the disintegration of Yugoslavia.

“At that time, as a citizen of Bosnia & Herzegovina, I could freely, meaning visa-free, enter only a few countries in the world. When I wished to enter Slovenia, I needed a visa that was very hard to get. Only 8 years prior to that, Slovenia and Bosnia were part of the same country. I would enter Slovenia through an entrance with the sign “OTHERS”. When Slovenians were traveling to European countries, they also would use the “OTHERS” entrance on the border crossing. Many things have changed since then, but it’s interesting to see it gain similar relevance in the context of Brexit. UK citizens could soon become “OTHERS”, too.”

TATE Modern acquired EU/Others just this year – and I can’t help but find the timing ironic.

As a first-generation Australian who returned to live in Bosnia & Herzegovina to better understand my own identity, I spent a lot of time getting to know Šejla. During one of our last encounters, I talked with her about her next project in the screen-printing studio of the Academy of Fine Arts in Sarajevo. She was pressing the message ‘The Party is Over’ onto hundreds of pieces of black and white clothing. “This project is a combination of public action, photo and film, examining the process of fashion disposal,” she said. “The first part of the action is symbolic: I will be returning over a hundred pieces of second-hand clothes found in the Balkans back to where they originated from in western European countries with the message “the party is over” printed over them.” She was planning to start by distributing the clothes on the streets of Berlin in the autumn. Her determination to tackle ecological issues doesn’t stop there: in another, parallel project, Thank God It’s Friday, she aims to capture a specific and contradictory moment of decline and enlightenment that arose from fossil fuel corruption. For this, she’s using an example of the decline of coal mining in Bosnia & Herzegovina. And in the small town of Istria, her second home, she’s developing a permanent installation that deals with migration and global mass tourism.

“I never wanted to make art just for a small group of people,” she says. “The urge to make art for me comes from the wish to communicate with everyone. I strongly believe that art is about communicating on an emotional level; and it is beautiful to see the different emotions and ideas that art provokes in people. If we agree that we see things differently, we can also agree that we all understand things differently, that our perspectives are unique.”

What is clearly apparent in Šejla’s work – in her art-as-resistance – is that, while many of the ideas she explores are born from personal struggles in Bosnia & Herzegovina, her concerns are relatable, universal, their subject matter crossing every geographic border. They are works of art rooted in the fight against systemic oppression. And, as one politician once said, the history of liberty is a history of resistance.

A huge thank you to Ennis for your thoughtful words on an iconic artist. Check out Ennis’s new book, an exploration of Bosnian and Herzegovinian identity, full of beautiful photography, poetry and short stories.