Mapping migration and precarity in Calais

Artist Stanislava Pinchuk (also known as Miso) maps war and conflict zones in the most delicate ways: recreating their changing topographies as pinpricks on paper. But conveying the forced evacuation of the Calais refugee encampment has led to an unusual choice of material: terrazzo.

What interests me, above all, is how the landscape is changed within war or conflict zones. How does topography hold the memory of a political event? How does ground provide evidence? Ruins tend not to lie.

Mapping land began a little without my realising it. At first, while living in Tokyo, it was informal, a way of recording myself in a huge, metabolic city. Plotting, dancing and drinking; lapses of memory. Then, while I was in Japan, my home, along the Ukraine’s eastern border, was invaded in an act of civil war. It was an experience that remains beyond words for me. Distant borders were shifting, and, with it, the potential threat to my citizenship. The ground beneath my feet suddenly felt like a strange fabric made of not knowing.

As an immigrant myself, I wondered how – or even if – my own path had left any physical remnant on any piece of ground along the way.

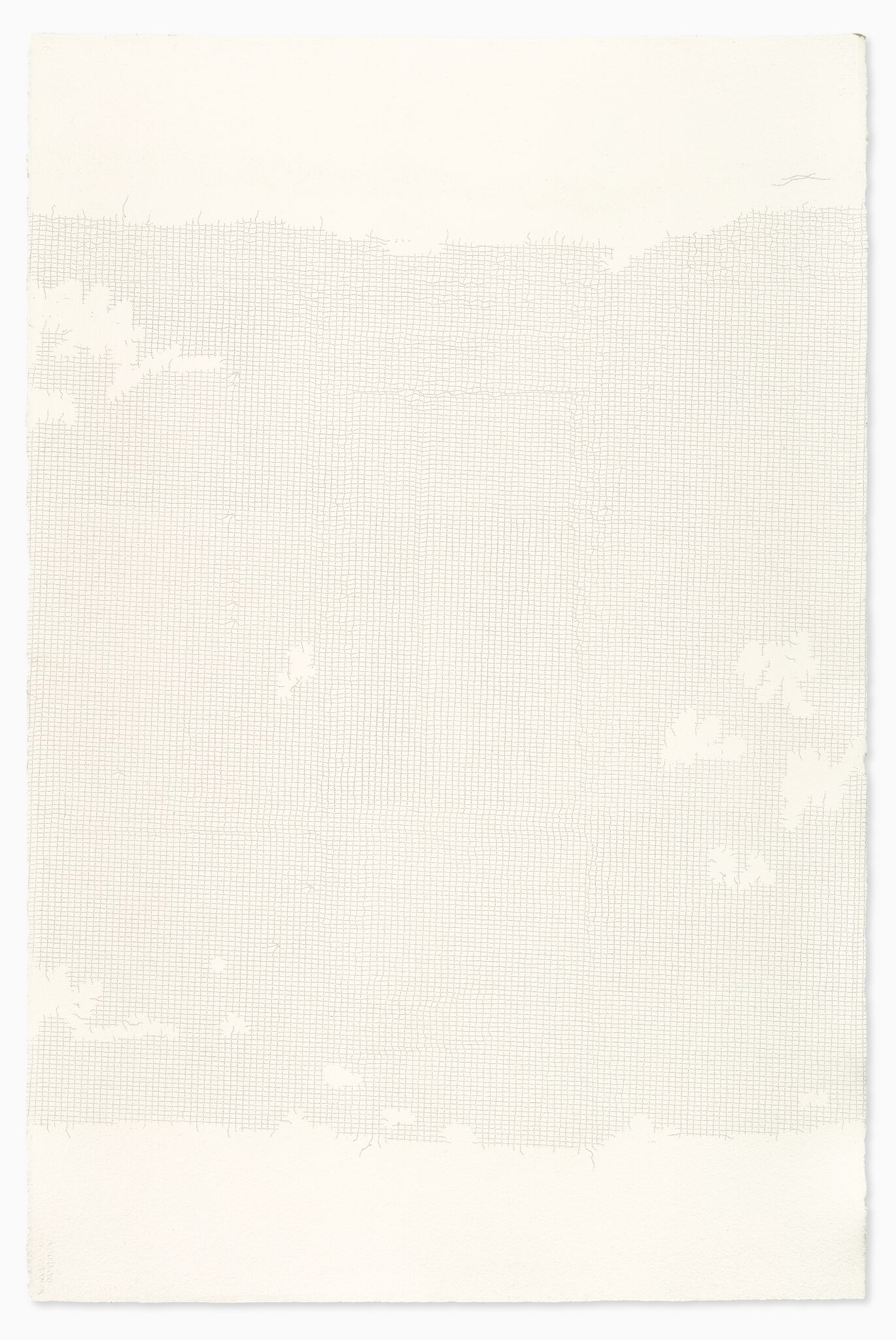

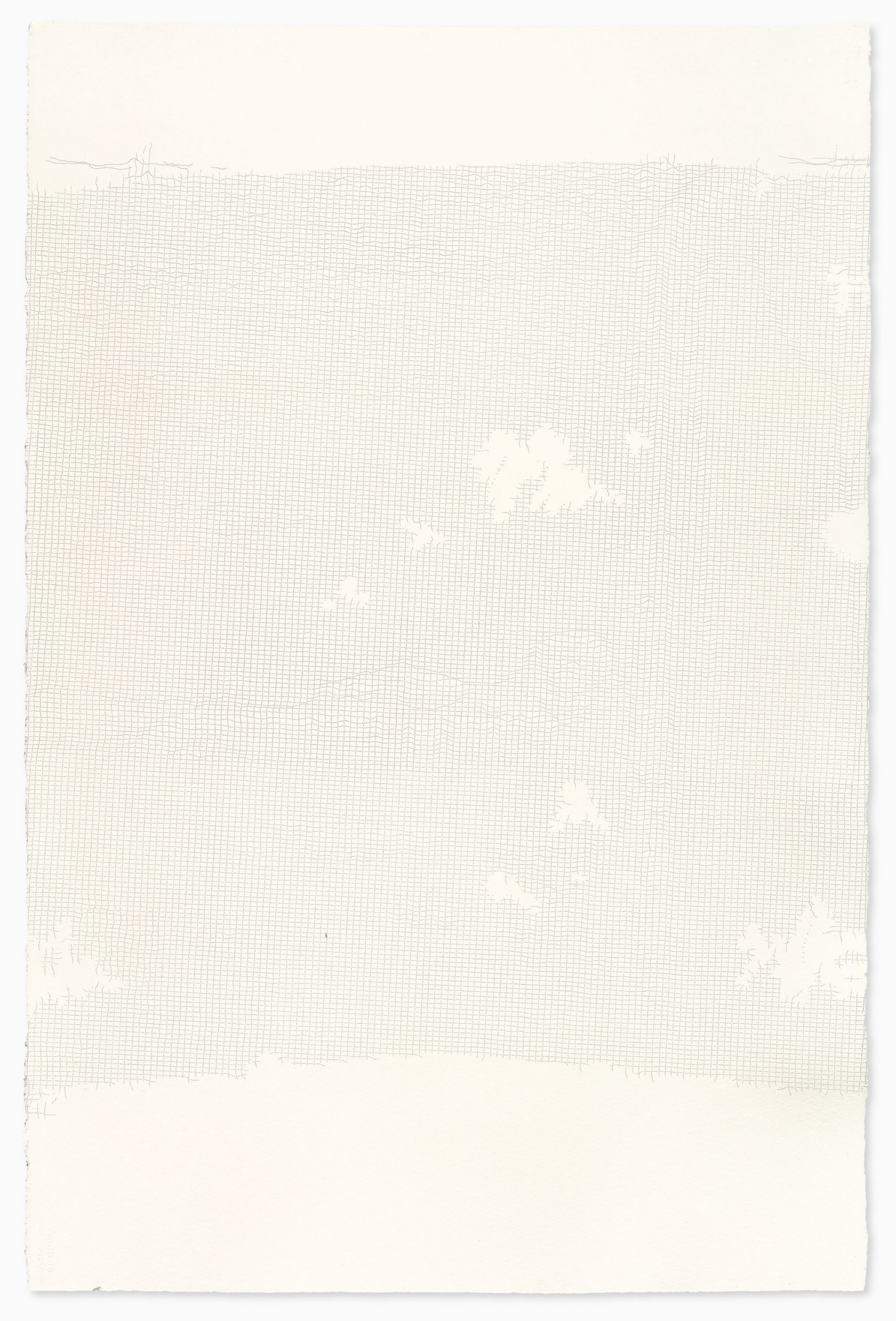

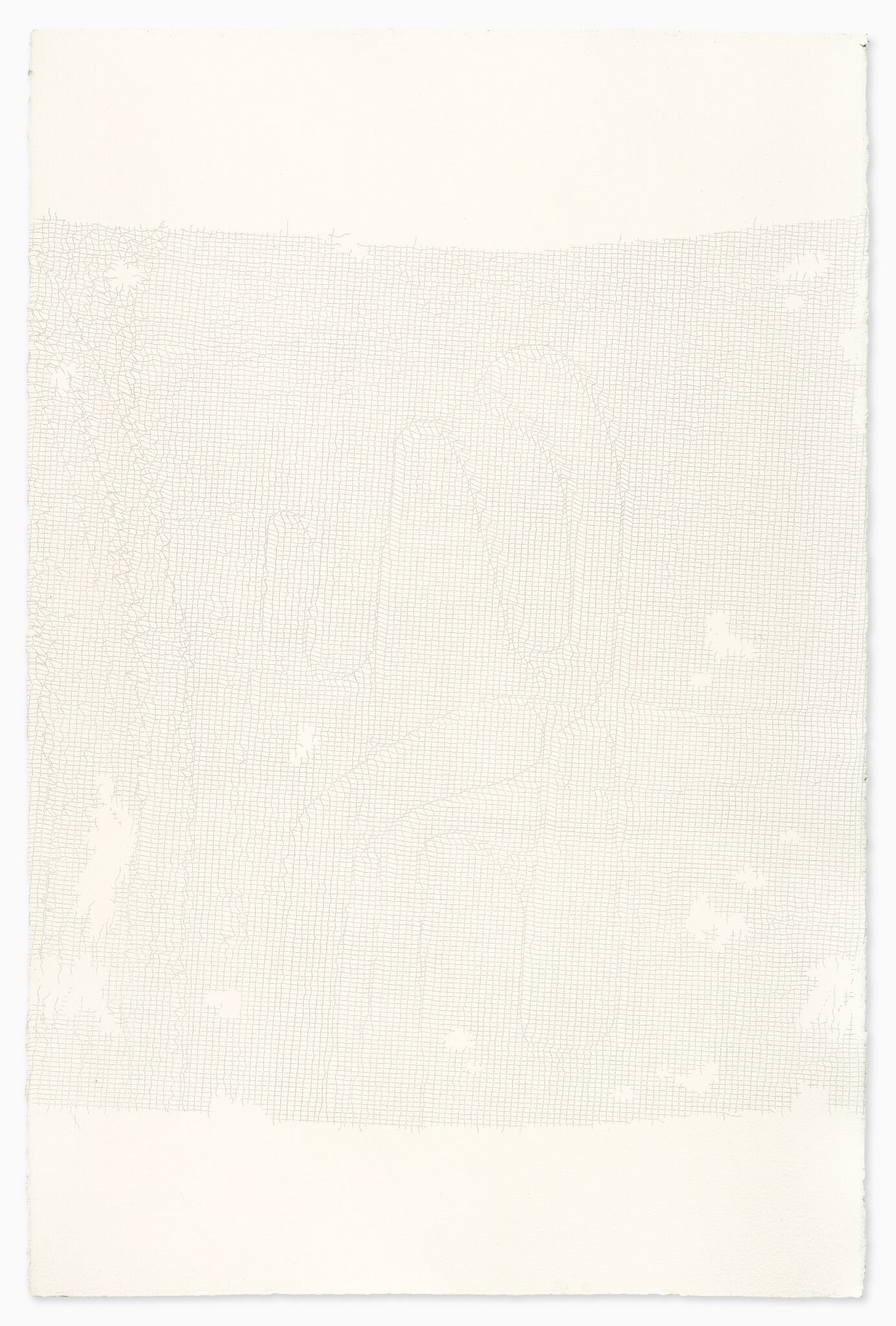

So, I began to survey, to collect data and preserve the land as digital meshes, to turn into white drawings. The drawings are plotted pin-hole by pin-hole, processed into the computer and then sewn into needlework by hand. Pain every step of the way.

Some years and projects later, I was working in Paris. Sensing the lead-up to, then witnessing, the forced evacuation of the Calais ‘Jungle’ migrant camp in 2016, I began to think of the ways immigration directly changes the shape of land. As an immigrant myself, I wondered how – or even if – my own path had left any physical remnant on any piece of ground along the way.

In all its iterations across roughly 17 years, Calais was a mostly informal settlement. It was not a camp built with the idea of containment or protection, but one based on the chance to make an escape from it, every night, into a ferry or lorry bound for England, from France’s closest geographic point on the other side of the Channel. But within the camp’s informality, the Jungle was an incredibly dense and layered social ecosystem. It housed supply shops and kiosks, numerous bakeries, restaurants and tea houses, libraries, a childcare centre, mosques and churches. The bonds between residents were tight, especially between the young men who had worked their way across Europe alone. But, above all, it was a place where many lone migration paths of multiple directions, lengths, reasons, demographics and levels of bureaucratic documentation – and paths often made relatively discreetly – collided to suddenly leave a deep mark on the land, right by the grey beach of Dunkirk. I often wondered if here was some geographic peculiarity; a hardness doomed to repeat itself for generations of young men.

The data drawings, an analogy for its modern reputation for political borders, are plotted into pieces of Calais lace (the tradition for which the city is known). Both lace and borders, it goes without saying, are often objects of intense human desire and longing.

In all my mapping work, I never interfere with the ground. The land is there to be documented, just as it appears. Nothing is added, and nothing is taken.

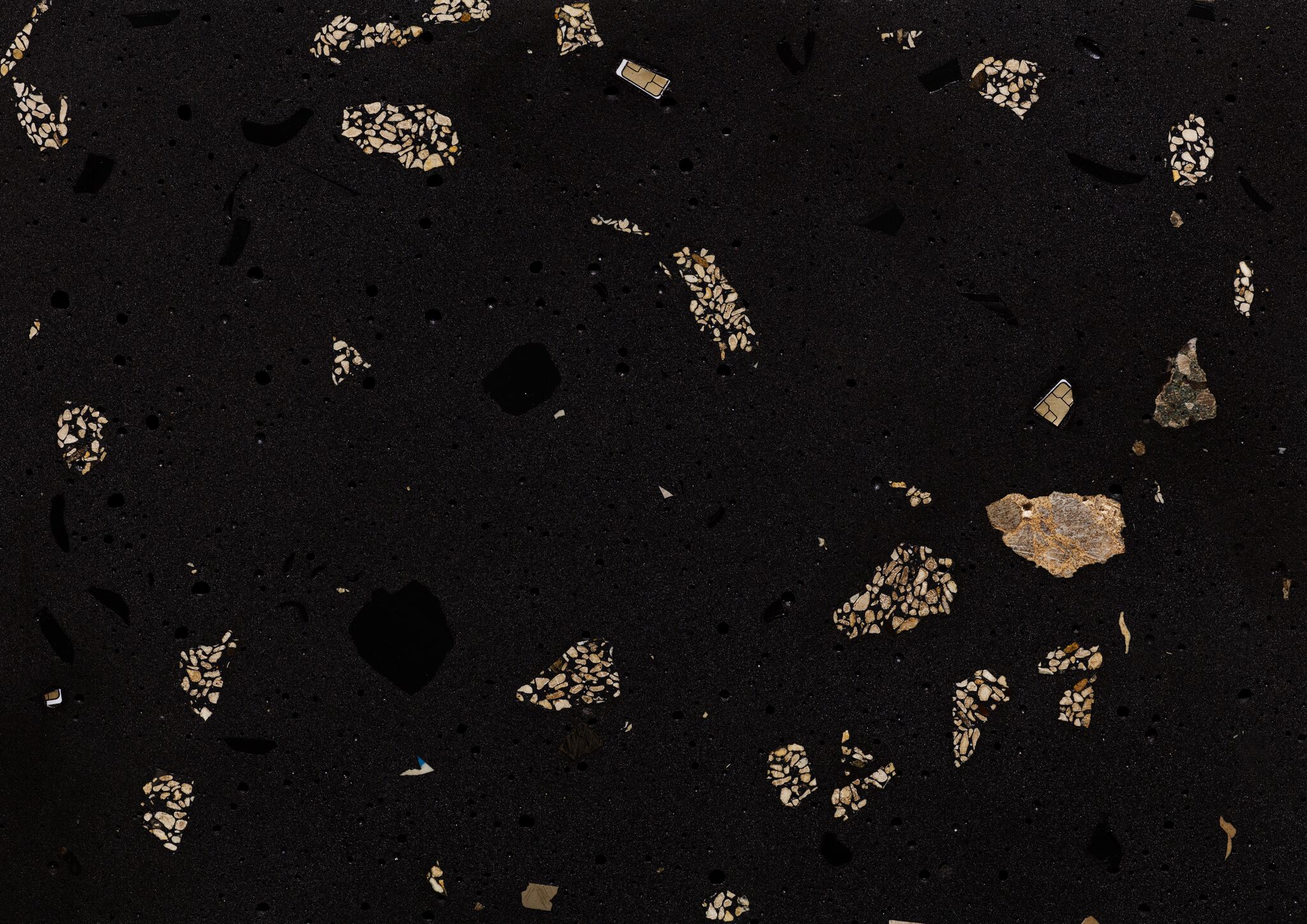

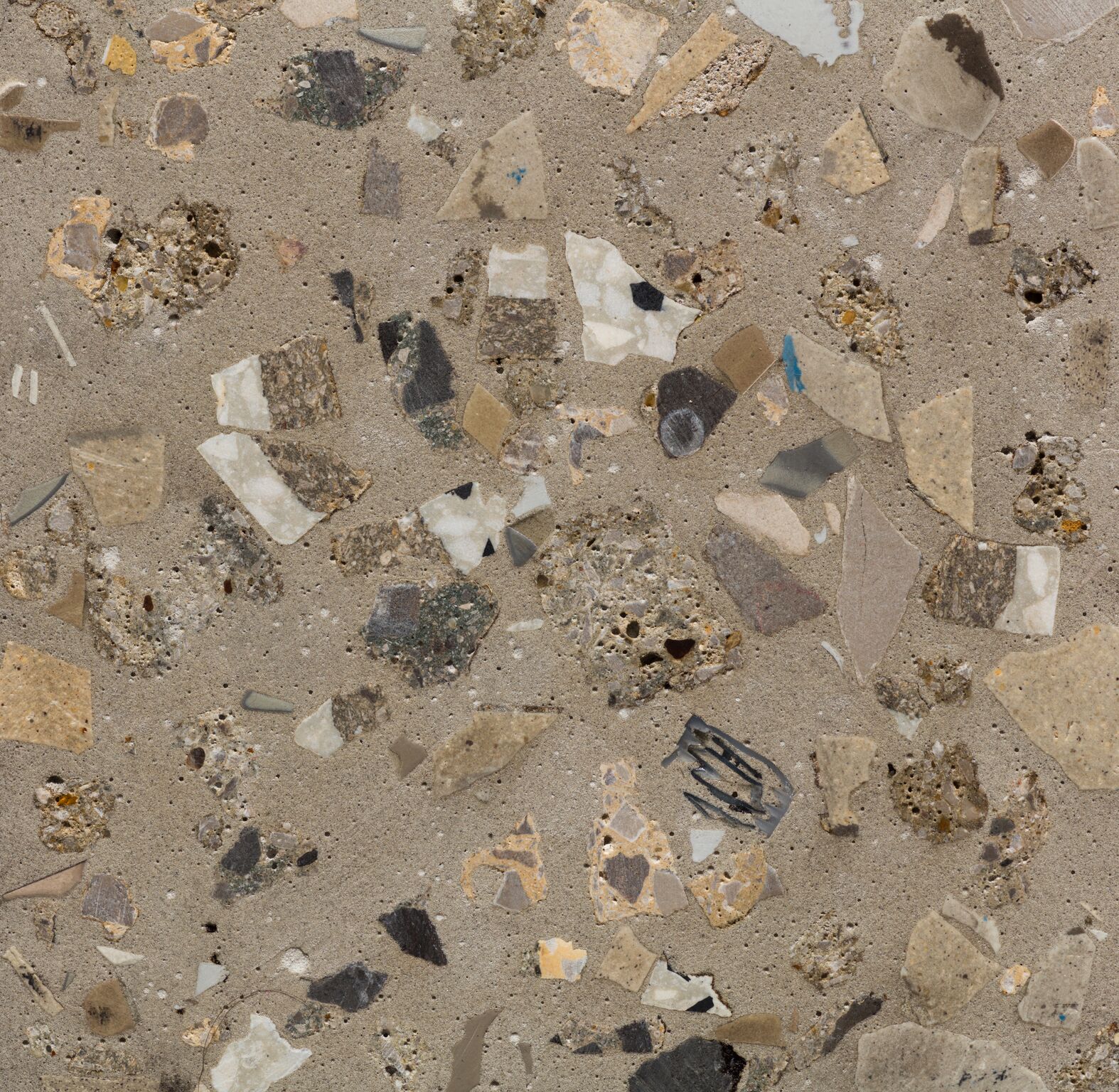

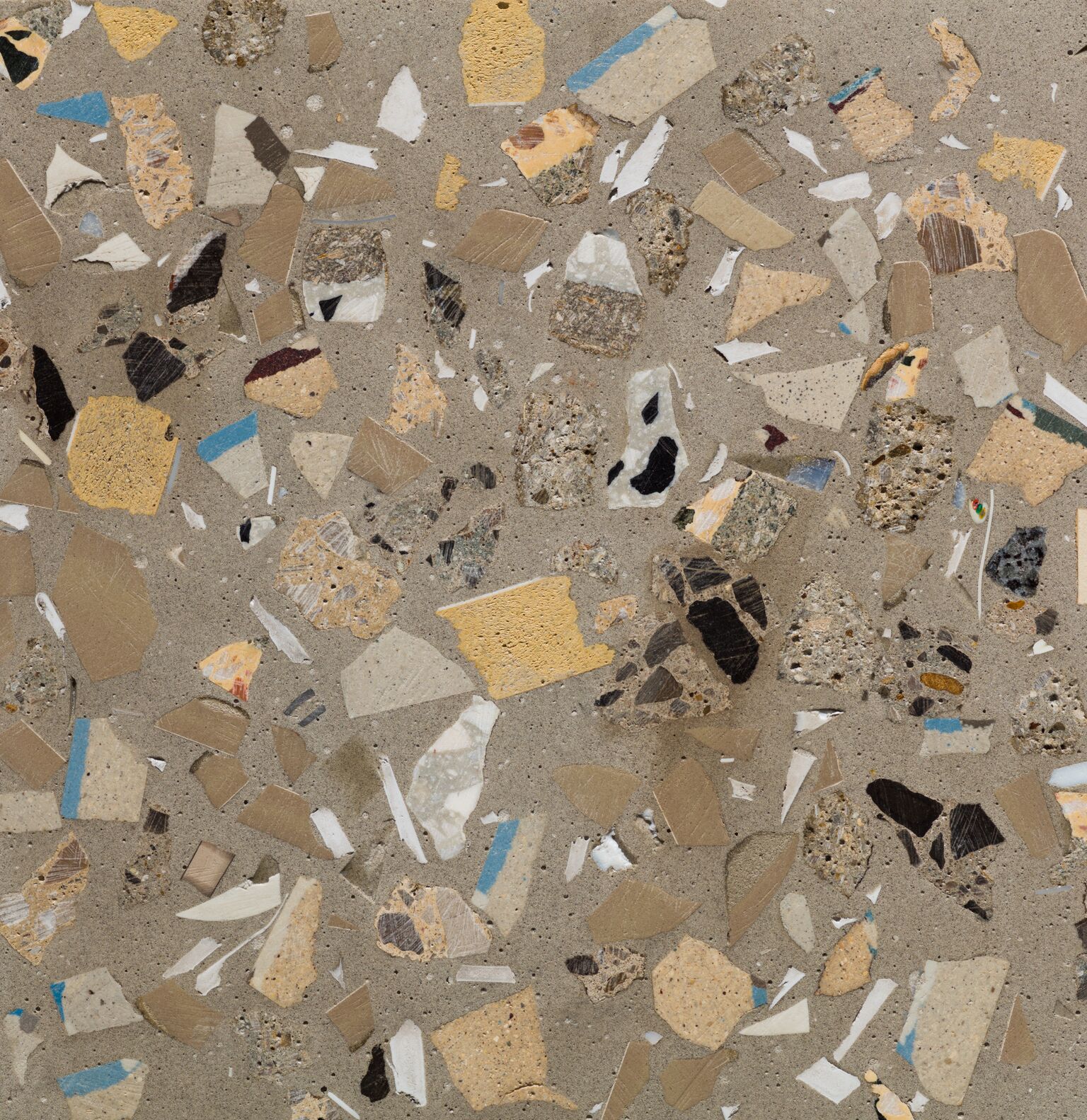

In mapping the six months following the forced and sudden evacuation, you can see the demolition lines made by the tractors and bulldozers across the entire camp. Among the smaller works is a map of perhaps the most callous act of the evacuation: the burning of the ground by the French authorities, which appeared to have no practical reasoning, other than the savagely symbolic. This micro-topography hangs among that of a trampled prayer mat, tent and shotgun shell, as well as a hiding hole, dug into a hill for a stealthier run-up for a passing lorry.

In all my mapping work, I never interfere with the ground. The land is there to be documented, just as it appears. Nothing is added, and nothing is taken. Nothing is swept, moved or edited. The ground is simply surveyed, and recorded in its exact state.

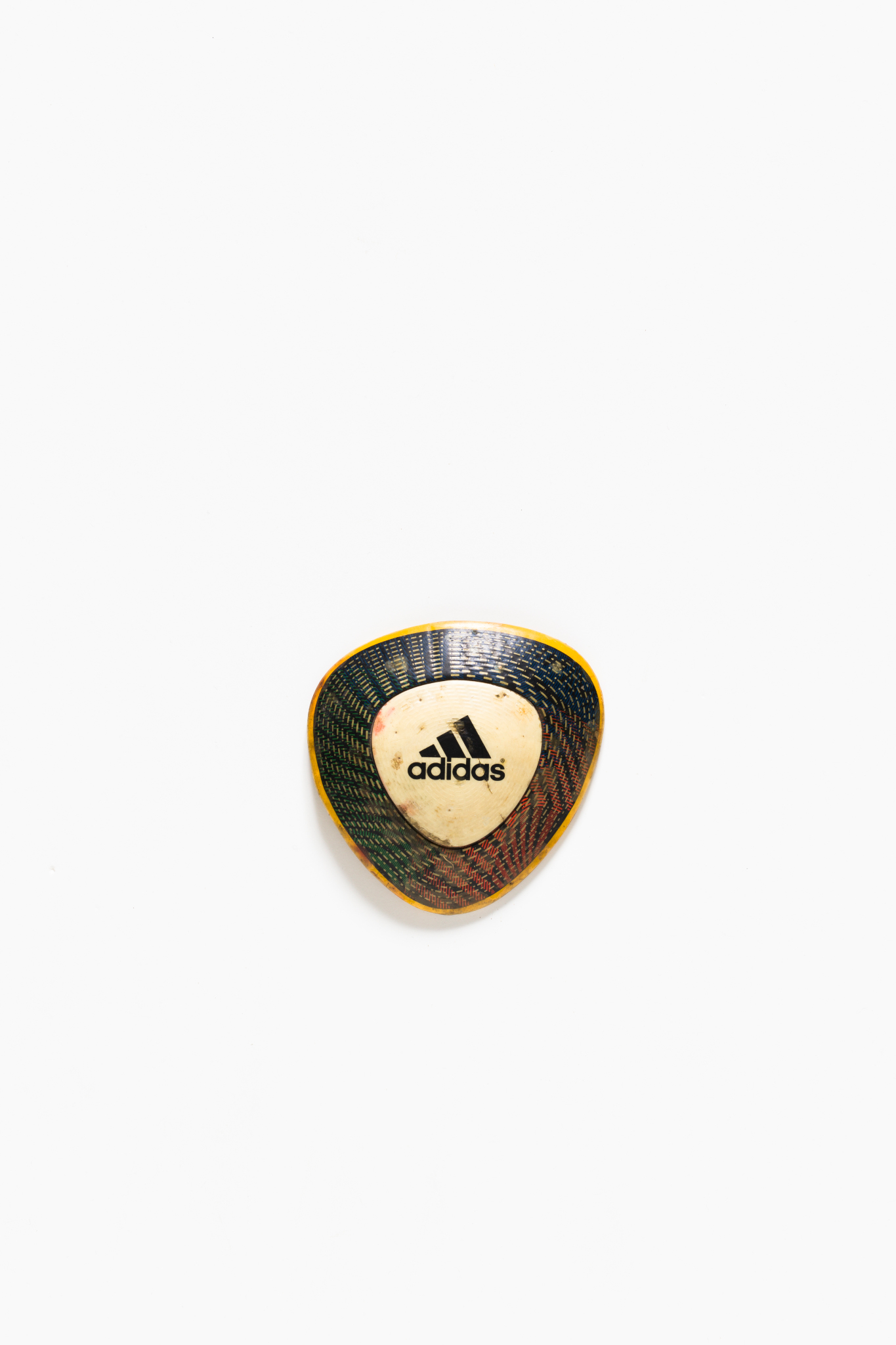

And yet, Calais took me aside. In most places of my previous work, especially in the Fukushima Daiichi and Chernobyl nuclear exclusion zones, the subtleties in landscape change are minute, and a challenge to attune to, even for the trained eye. But in Calais, the Jungle was a landscape of thousands of objects trampled into the ground, a mosaic of overwhelming information as far as the eye could see; something between an archaeological dig and a terrazzo floor.

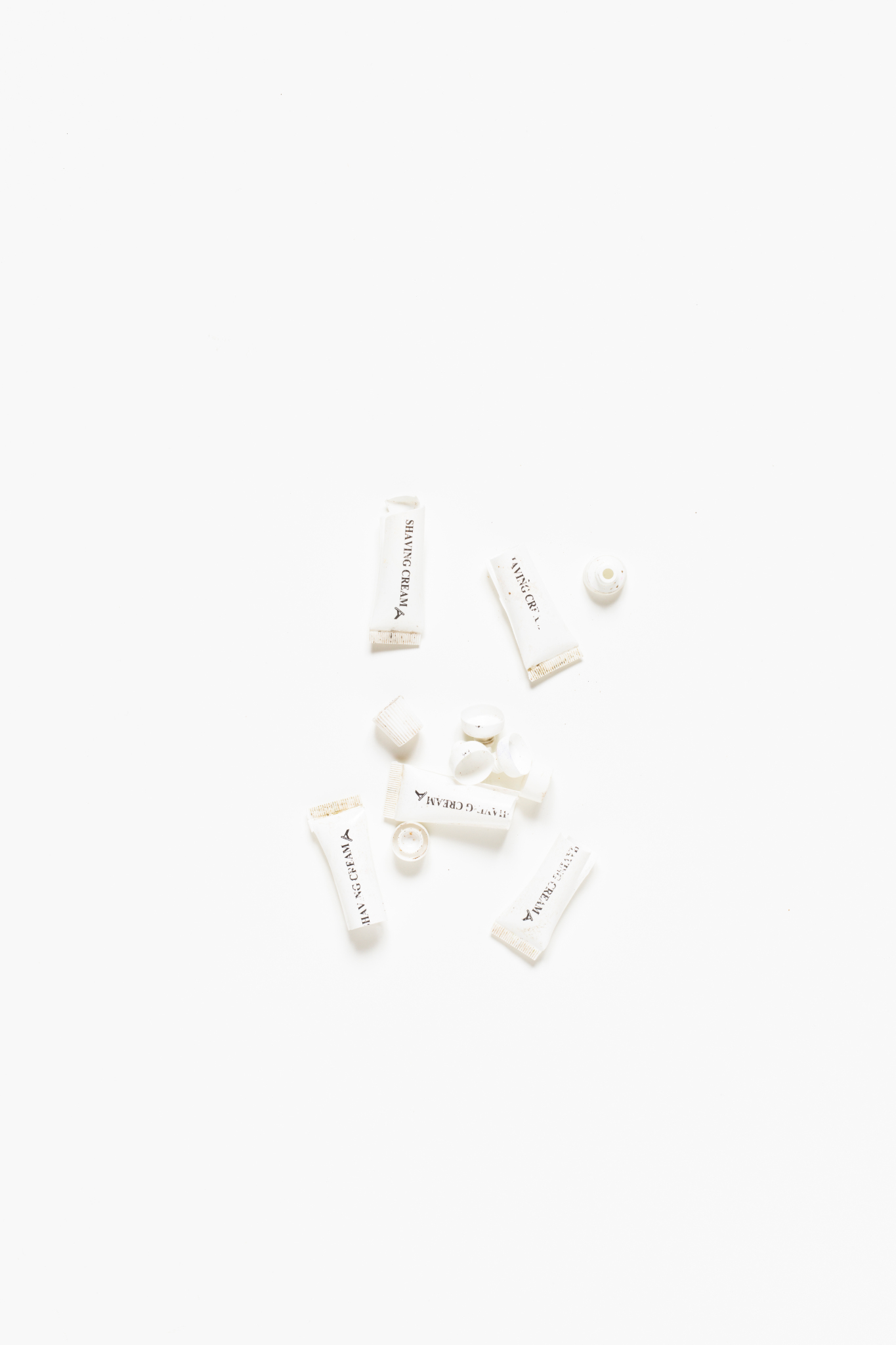

So, for the first time, I broke my rule. On the very last days of the camp’s razing, and my very last stretch of surveying its topography – a bitterly cold day, between two snowfalls – I collected the last remaining 20 kilograms of the campsite for preservation. Tents, shoes, shotgun shells, watch straps, shaving cream, kiosk tiles and plastic plumbing. Nutella lids, watch straps, buttons, electronics and blankets.

Over seven hours, I scraped, excavated and sifted through the debris and hauled my collection onto a late-night train to Paris. I scrubbed it all clean in a bathtub, with vinegar coating the shotgun residue of all the objects. I packed everything like drugs. Fearing the loss of these last, irreplaceable remnants through a courier service, I carried them with me across nine destinations, from France to Spain, through the Sahara desert and Atlas Mountains. I was stopped at every border crossing, searched and questioned; miraculously, I made it through Australia’s strict customs most easily of all. (If you must know, the secret is a decoy top layer of declarations: Saharan honey jars, Tangier’s finest straw baskets, and underwear.)

Removing the sculptures from their moulds was where the works really began to make sense.

In Melbourne, every object was immaculately photographed and documented – and then pulverised, irrevocably set into sculptural terrazzo blocks. Crushed and trampled all over again, the objects were colour-coded and arranged with just enough cues on the outside edges to catch the eye: the shine of a rough-cut aluminium tent pole, or the smooth edge of a plastic drink lid. Pulling in even closer, you would be able to see the shape of a watch strap, a toothbrush handle or half a razor, gleaming from the block just as they did on the campground in the frost.

Removing the sculptures from their moulds was where the works really began to make sense. Here were slightly boring blocks, plain on the surface at first, like samples in an architect’s office. And that was exactly the power of terrazzo for me – a building material full of recycled elements, used for both interior and exterior spaces.

It seemed so fitting, given not only the material recycling and resourcefulness of the Jungle’s dwellings, but the very public nature of the domestic lives within the camp. Here were thousands of parts, mixed together into one amalgamated whole.

A very heartfelt thanks to Stan for giving us an insight into her project of mapping ‘Jungle’. This article also appears in AP print issue #11: Transitions, available for free in many good places.