A spatial artistic revolution at Ruhrtriennale 2018

Ruhrtriennale is a festival of art nested within architecture. Taking place in some of the world’s most imposing industrial ruins, it has pioneered an innovative approach to protecting industrial buildings and highlighting their cultural legacy. Manuel Zabel went to the Ruhr region to see for himself.

Founded in 2002, the Ruhrtriennale theatre festival has worked successfully towards international recognition. The roots of the festival go back almost a half century, when factories were shut down in great numbers as the coal and steel industry declined in the Ruhr region. Huge industrial buildings, some of the oldest in the world, were reclassified as monuments. Repurposing them for cultural events, with the Ruhrtriennale program at the forefront, triggered the region’s structural change: the festival’s founding father Gerard Mortier introduced the idea of cultural events staged not just in significant industrial buildings, but in dialogue with them. Language, music and dance were added to the mix, and out came a multimedia hybrid of architecture, landscape, words, sounds, images and gestures. Though annual, the series of events owes its name to the underlying concept of bringing in a new artistic director every three years. The current season, curated by German dramaturg Stephanie Carp and Swiss theatre director Christoph Marthaler, runs from 2018 through 2020.

This summer, I travelled to the Ruhr region to see some of the program, which promised to (re)evaluate deep-seated parameters of economics and identity. Migration was stressed as a pervasive force that resonates throughout the land. The program encouraged us to engage in the transition period, the “in-between” time, and celebrated participation, equality and freedom for the sake of social and cultural relations beyond political taste. August and September were filled with “in-between” art forms: musical theatre, choreographic performances, installations, concerts and talks. Fair enough. But then, contrary to the concept, two concerts found themselves in the crosshairs of opposing political views, and were controversially cancelled. And Stefanie Carp, the current artistic director, at times at least appeared to be a pawn in the hands of opposing political camps.

What can make the Ruhrtriennale truly overwhelming is its scenographic quality. Venues really do their part, not only as backdrops, but as if evolving from the very performances that they accommodate. The histories, traces and signs embedded in the buildings come into interplay with the art, sometimes intentionally, sometimes through the perception of the viewer. It is powerful: visual space becomes a performative space, becomes an atmospheric space, becomes an illusionary space.

This played out well in the subtle piece Universe, Incomplete. Christoph Marthaler, associated artist of the Ruhrtriennale and Ibsen laureate, presented fragments of Charles Ives’ unfinished Universe Symphony in the Jahrhunderthalle in Bochum. Formerly part of one of the largest steel plants in the Ruhr region, it was decommissioned in the late 1960s. The overall character of the hall was left untouched, and the building documents a century of changes in the plant and the city, their two histories inextricably linked. Universe, Incomplete dismissed the classic separation of audience and stage, putting to use the enormous physical dimensions of the space to realise a variety of spatial constellation, giving room to bodily and tonal movements.

It is stunning what can be brought to attentive ears in the vastness of the hall. An impressive array of around 150 musicians were occasionally swallowed up by the interior, even hidden from the spectator’s eye, but not so the sound. Two pianos faced each other, in wide distance, but only slightly offset sound-wise. Dissonant, repetitive, playing catch with questions and answers. A single voice, a chamber ensemble, a choir, or the complete line-up of the Bochum Symphony Orchestra – they were all conjured up in various ways, devoured by props and revealed again. From a tender whisper, clear and precise, to unmistakable affects released as sound waves from above, behind or in front of the audience: even the invisible remained audible.

Mamela Nyamza’s Black Privilege was a work that seemed to strive for ambivalence, even discomposure. Nyamza, a dancer, activist and black queer mother, lives in a South Africa shaken by discriminatory divides. Black Privilege, an antonym, channeled abusive conditions in a patriarchal society, carving out power structures as Nyamza moved between agency and the loss of control. The performance was staged in the old change- and washhouse of the Zeche Zollverein in Essen, a colliery-turned-World Heritage Site and largest of its kind in the Ruhr region. Soap holders and tiles still reflect the old spirit of the building. The shadowy, dimly lit scenery emerged as a zone of judgement and denunciation. The audience was steered into a space reminiscent of a courtroom. Spectators became jury members on both side wings encroaching on the stage. Nyamza was wheeled in on a high stand, the elevation alone suggesting hierarchy through architecture. Nobody quite knew though if her assistant was a servant or an authority. “Please rise!”, he addressed his audience; we immediately rose and sat down again.

For the duration of the performance piece, the audience was forced to reflect on the double meaning attached to props, actors, space and the whole setting, as Nyamza played on cultural projections. Superiority and subordination became very real, two sides of one coin. Like Marthaler’s, Nyamza’s universe remained ambiguous, as she slipped between roles of high and low standing – but mostly as she slipped right off the ladder of success. Privileges come and go with one’s point of view. The square stage exhibited Nyamza’s body like a celebrated object: exotic, bronze-coloured, sparsely clad in metallic body jewelry. She played on “our” image of the exoticism of faraway places. At the end of her spectacle of deconstruction, Nyamza’s companion asked the audience to leave the venue. Timid clapping was nipped in the bud. Applause is uncalled for when social complicity is revealed. Embarrassing discomfort. Silence.

Indian philosopher Nikita Dhawan exposed invisible colonial traces in the arts, voicing her sceptical response to the cosmopolitan idea of global solidarity – which neatly tied into the political turmoil surrounding the festival. “We might be facing the same storm, but we are not in the same boat”, she said in what Raumlabor Berlin calls “third space”, a public square sheltering plane parts symbolising both society’s crash and reconstruction. For philosopher Michel Foucault spaces were reflections of social conditions. Raumlabor Berlin’s intervention aimed to restore public spaces as spaces for community and communication. The public was invited to exchange their views in an “unmediated” way and help convert the structure, which will continue over the course of the next three years. Raumlabor Berlin’s interior, in some spots meticulously designed, featured events about community-building, and was intended to bear participatory potential, drawing people into reflection in the manner of the Socrates’ Athens. An architectural structure shaped by participation, in other words, as a representation of societies. Good idea, but I would be surprised to see anything like a Socratic public emerging.

Mariano Pensotti’s six-hour-long Diamante, a tale of the restructuring of a city run like a company, was staged in the Kraftzentrale in Duisburg, one of the biggest industrial halls in the region and now part of an almost dystopian post-industrial park. Though it was entertaining to walk through and gaze into the truly immersive made-up movie set, the piece came off more as soap opera than a melodrama. Later, I stopped by Peggy Buth’s documentary video work on former labour conflicts and current social conditions in the Ruhr region, screened in the deconsecrated, architecturally exceptional church of St. Barbara.

The church got its name from the patron saint of the miners, and was built in the 1960s on the premises belonging to the colliery Rheinhausen AG in a workers’ settlement, in close proximity to the very place where, beginning in the late 1980s, labour disputes shown in Buth’s work started to take shape. Interestingly, at the end of World War II, destruction and social unrest were followed by public renewal, and the booming years of the post-war era have decisively shaped the image of the Ruhr region. The spirit of architectural experiments is reflected in a wide range of structures to this day. Churches were no exception: daring and innovative, reflecting the social reform movements of the 1960s, they still rank among the most extraordinary buildings that can be discovered in the Ruhr region.

However, this Ruhrtriennale may be best remembered for political indignation, which took place even before the arts events officially kicked in. The Hezarfen Ensemble from Turkey was scheduled to present their Music of Displacement, with its central theme the violent events in Armenia a hundred years back. The program spoke of forced resettlements, but not of genocide, and Carp was accused of taking on board the very language used by the Turkish government, which to this day denies the atrocities. The festival responded with a claim to be protecting the musicians from a backlash in their home country. The Ensemble eventually withdrew from the program, leaving Ruhrtriennale with a minor public relations debacle. As if that was not enough, the Scottish hip-hop band Young Fathers came under pressure for their support of the BDS campaign. The campaign [Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions] demands the economic and cultural isolation of Israel because of its settler colonialism and apartheid practices in Palestine. For some, supporting BDS amounts to antisemitism, which is a rather delicate issue in Germany; for others, opposing BDS is itself racist. Carp first backtracked by uninviting Young Fathers, then recanted and re-invited them – only the second time they rejected the offer.

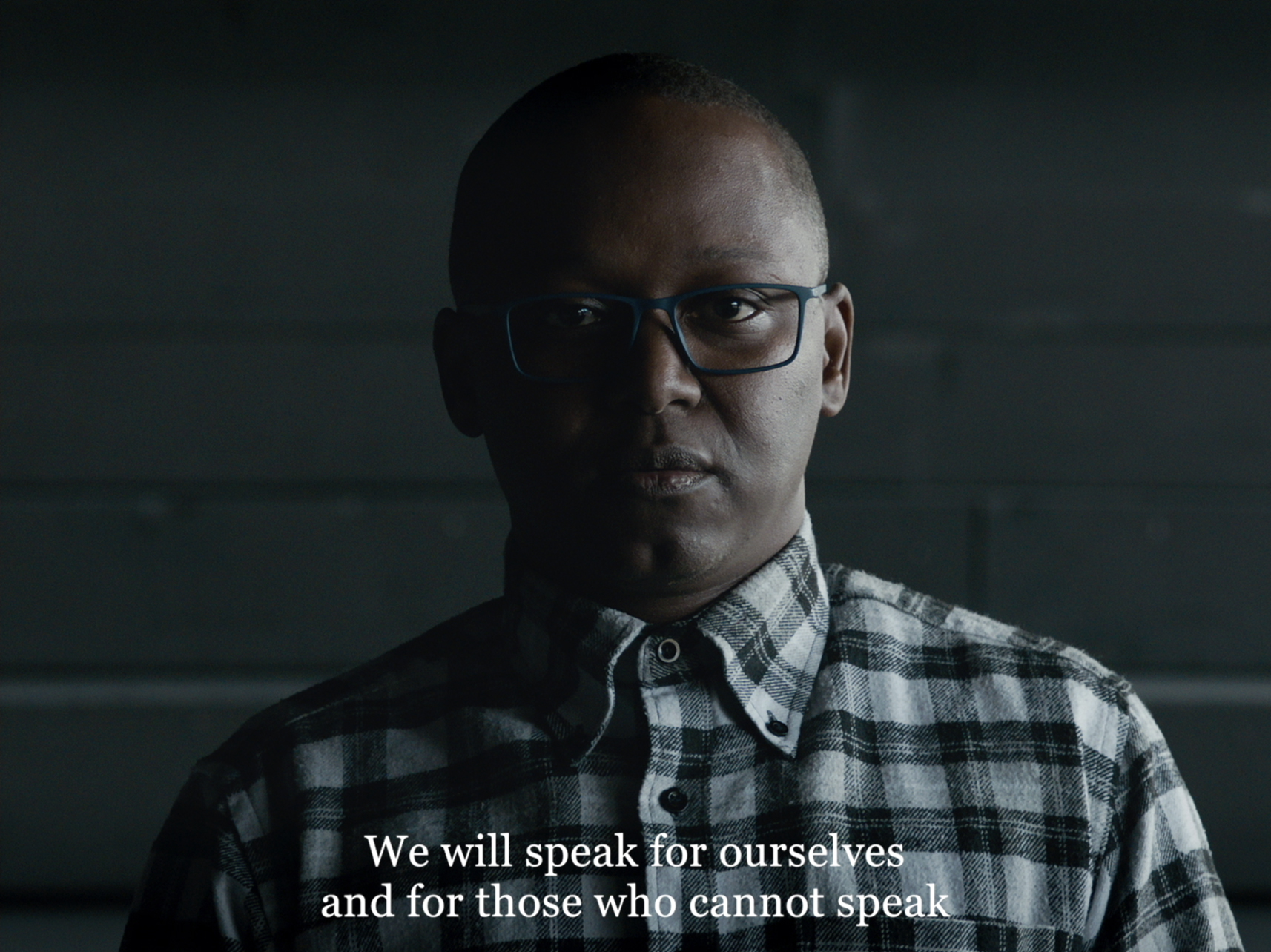

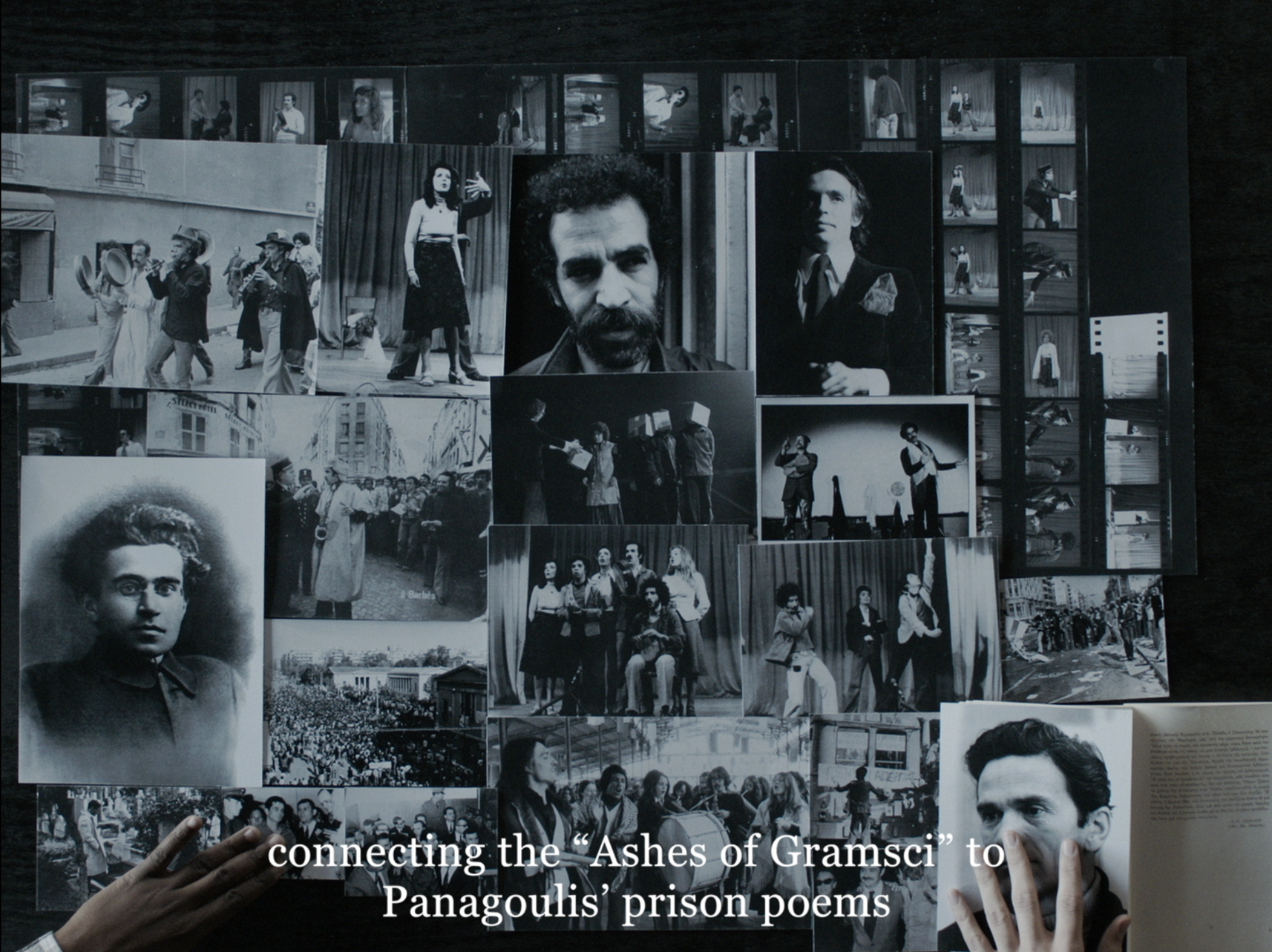

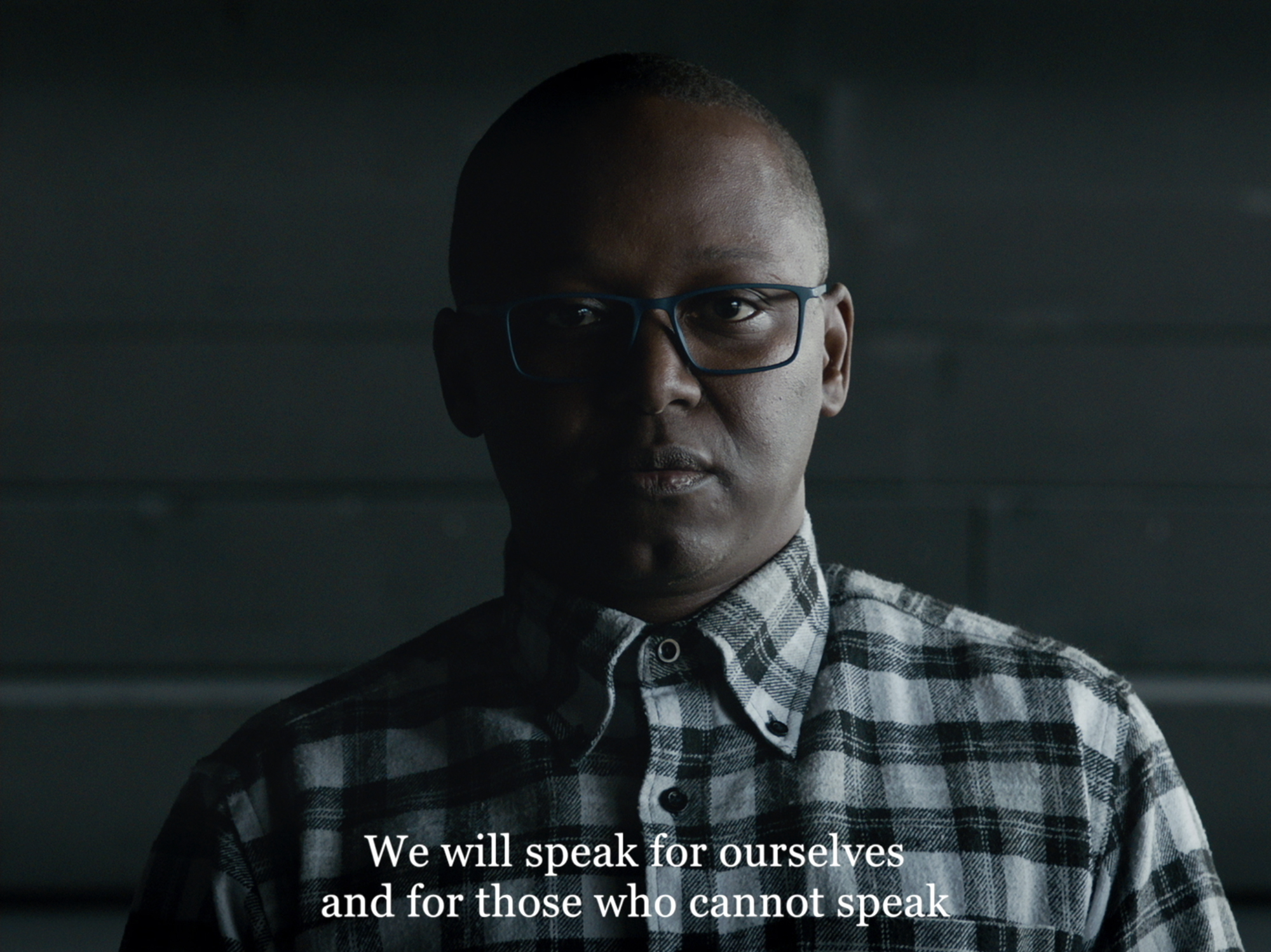

Rounding off the condensed trip to Ruhr, I saw Bouchra Khalili’s Twenty-Two Hours, a video work on the Black Power Movement (BPM) and an indirect elaboration on the art (and importance) of story-telling. The documentary-like work made history resonate within the present. In their time, the Black Panthers faced anger and violence. Today, their cause is showcased in museums. BPM and BDS are not comparable, but there are similarities. Both movements create agency for an oppressed group to speak for themselves – and others.

These may not go down as the Ruhrtriennale’s most glorious first days. But how will they resonate in the future? The festival’s innovative theatre practice is largely shaped by the region’s industrial buildings, which carry in their bones stories from the past. We owe their preservation to the early mobilisation of the local citizens – who advocated to prevent demolition, but also forced the government to rethink what heritage protection means. The change of thinking, which expanded the notion of ‘monument’ beyond art, to include industry buildings, emerged slowly in the 1970s, but represented nothing less than a paradigm shift: today the aesthetic merit of these buildings is widely accepted. The Ruhrtriennale has to be given much credit for nurturing this spatial and artistic evolution.

Ruhrtriennale is one of our favourite art festivals, for its sensitive engagement with socially challenging urban heritage. A warm thank you to the Ruhrtriennale for letting us into their spaces and performances, and to Manuel for bringing it all together. Stay updated about the rest of the Ruhrtriennale program – which runs continuously, despite the name – on their website. Tschüß!