Eugenia Lim reflects on ugly-beautiful Australia

“There can be few other nations less certain than Australia as to what they are and where they are,” wrote Robin Boyd in The Australian Ugliness (1960), his examination of the national aesthetics. In 2018, artist and Assemble Papers founding editor Eugenia Lim contemporised the book’s provocations in a video installation that will soon travel to Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA) for The National 2019. Here, Lim reflects on the book’s enduring themes – and how our relationship to architecture is as personal as it is political.

The first time I read The Australian Ugliness, it was the height of summer. I was staying in a suburban-style weatherboard house in a town called Mount Beauty in Victoria’s north-east. The air-con was full-tilt; the January heat easily permeated timber and plasterboard. The house and me within it baked. It was clear that mod-cons and add-ons are no match for the Australian climate – without context-sensitive design, the heat and the vastness will always win.

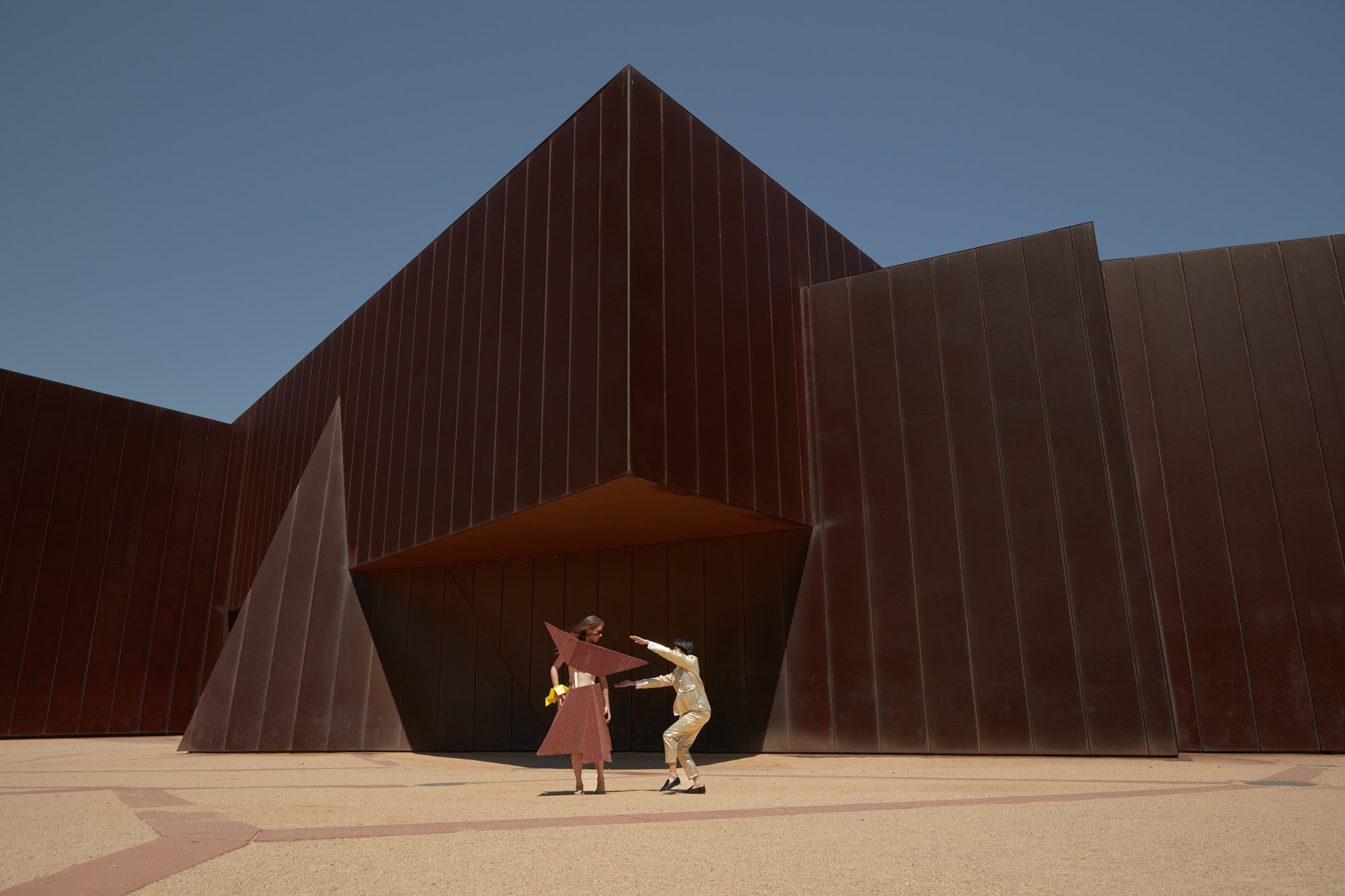

If architecture is the reimagining of the world as human, what do our buildings say about us? Through choreographed actions and interventions by ambiguous, coloured, ageing or queer bodies into the icons and interiors of Australia, my take on ‘Ugliness’ seeks to question: who holds the right to design our spaces, and who are they designed for? Who shapes our built environment and in turn, how do these forces shape us? In his polemic book, Robin Boyd merged architectural and human skins, suggesting that the way we mask, Alucobond ® or distract in our built environments is an allegory for ourselves: “The ugliness I mean is skin deep… But skin is as important as its admirers like to make it, and Australians make much of it. This is a country of many colourful, patterned, plastic veneers, of brick-veneer villas, and the White Australia Policy.” Boyd equated our tendency towards the kitsch, the macho and the superficial to a deeper aesthetic and ethical gap in the national psyche. He called this ‘featurism’: a satisfaction with the mediocre or cosmetic. Fifty years on we are more self-aware and globalised, yet featurism is still deployed to mask the ingrained colonial fiction of terra nullius; of Indigenous subjugation; of our inhumane treatment of refugees; and a culture that still privileges the white, the male, and the monumental.

As an Australian who is none of those things, I want to continue Boyd’s line of culture-making, to reflect back a vision of this country that is more cacophonous and feminist: both ugly and beautiful. In my work, I take up Boyd’s provocations – of identity, place, design and class – but I bring to these my own experiences as a woman, non-architect and Asian-Australian (an identity largely invisible or under-represented in architecture and architectural discourse). The work is a challenge to both the profession and the public: architecture shapes us, and we all must have agency in this process of who we become.

In his introduction to the House of ideas catalogue, Philip Goad writes that Boyd was a man of ideas who believed design was a practice of “public action with public consequences”. This too is a project that seeks to collide the field of architecture with the every-people who inhabit it, through the projection of ideas. Reflecting on Boyd’s Antiarchitecture, Naomi Stead writes: “Maybe its time has come… to overcome our docile apathy, our polite fatalism, our beholdenness to (apolitical) disciplinary institutions and (repressive) disciplinary canons. Maybe it’s time we finally found our passion and our righteous fury, and joined the protest. Maybe the moment is finally here: to smash open the core of architecture, and be ready to embrace the ‘absolutely different’ social and political antiarchitectural practices we find inside.”

In the work, I shape-shift as ‘the Ambassador’ across more than 30 sites and spaces across Australia, from Wood Marsh’s enigmatic Gottlieb House (1994) to Peter McIntyre’s elegantly engineered River House (1954) and Cassandra Complex’s ‘trophy home’ for the Smiths, the Smith Great Aussie Home (2006). We visit 91-year-old Myra Demetriou in Tao Gofer’s brutalist social housing project Sirius (1978) in the months before she is forced out and the site of Sydney’s contemporary ‘culture wars’ goes on the market. Looking back to Melbourne from Craigieburn, the work considers the limits of architecture – where are architects absent? Curator and architect Rory Hyde observes that today, architecture is notably absent from the suburbs of Australia, “hitching its wagon to the boutique luxury apartment market of the inner ring. Could these issues be addressed with a new Small Homes Service for today? What would such a program look like? And if he were here now, what would Boyd do?”

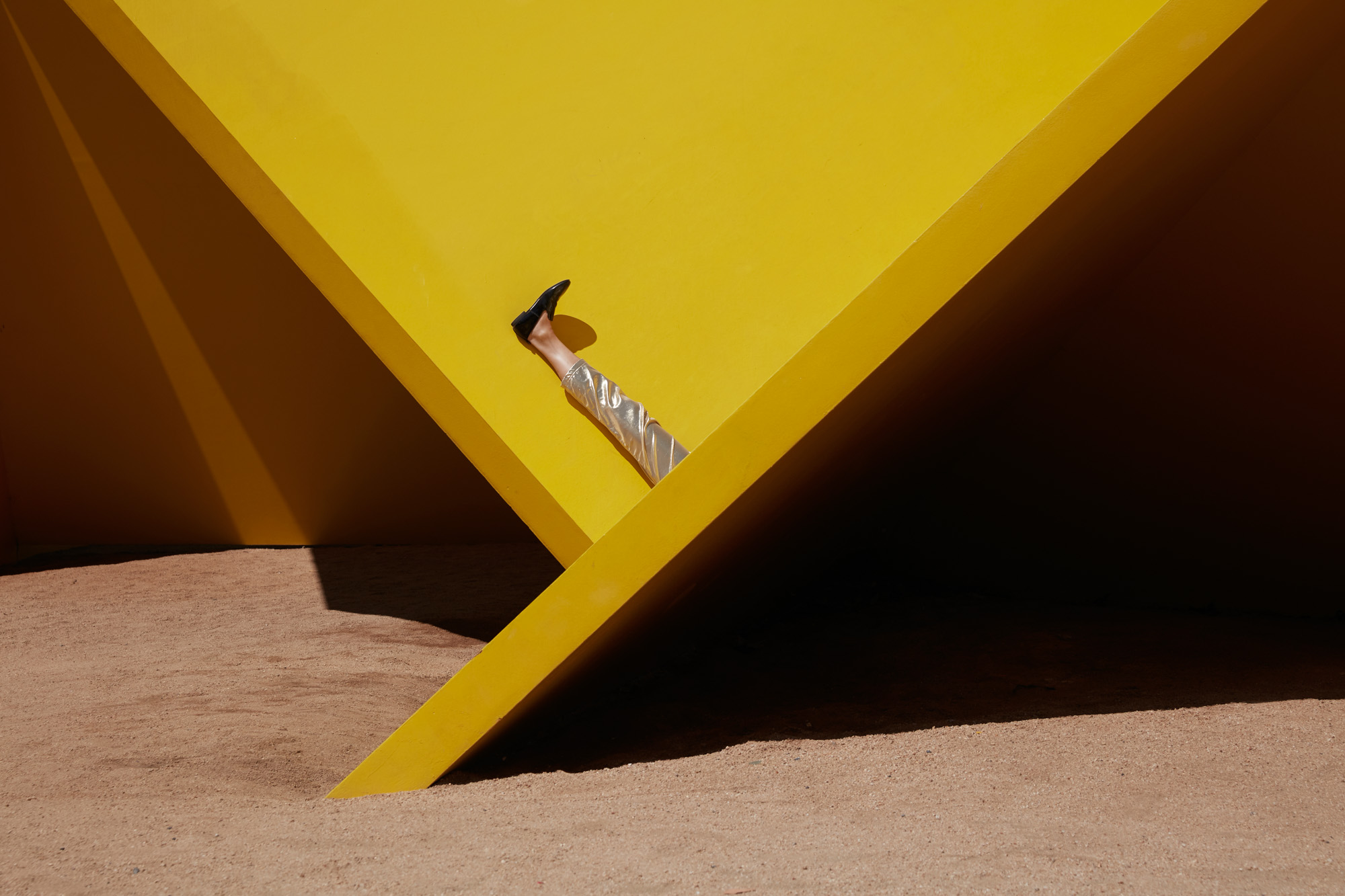

A site of ‘eternal return’ in the work is Boyd’s home designed in 1957 for his family in Walsh Street, South Yarra. In 2016-17, I spent time as an artist-in-residence at both Walsh Street and Robin’s cousin Arthur Boyd’s Bundanon (NSW). These experiences of researching and experimenting in sites of Boyd’s work and life have infused this project which, like Boyd’s book, is a site-responsive love letter and critique of our national identity and context. Viewers experience the work in a yellow and gold pavilion, a reimagining of Neptune’s Fishbowl (1970) in South Yarra, one of Boyd’s last projects. Yellow is a direct reference to Ron Robertson-Swann’s Vault (1978) or ‘yellow peril’ – a colour that continues to permeate the built fabric of Melbourne and beyond. For John Denton of DCM, original commissioners of Vault and repeat-users of yellow in their architecture, yellow is a provocation: a sign that “design culture has won.” ARM deploys the ‘yellow peril’ typology and colour almost obsessively – even in Asia. As an Asian-Australian born and based in Melbourne, ‘yellow peril’ is in my blood. And, it’s become my own visual shorthand to collide a personal, national and geopolitical exploration of identity.

Thank you, Euge, for this timely provocation. The Australian Ugliness was first presented by Open House Melbourne and Melbourne School of Design in July-August 2018. If you’re in Adelaide, go see Eugenia’s solo exhibition The Ambassador as part of Adelaide//International, or head to Sydney for The National 2019.