A Saturday spent at Women Design

To commemorate 100 years of women’s vote in Britain, a two-day symposium on women in design took place at Design Museum, promising to explore historical injustices and analyse contemporary design culture. Kate Riggs was in attendance.

‘I remember sitting in a bathroom cubicle, flushing the toilet to mask the sound of my breast pump; ashamed and unsure where else to go when tutoring in a twelve-hour crit.’

An intimate confession set a personal tone that reverberated throughout Women Design, a two-day program of talks at Design Museum. We were there to talk and learn about women in design – at school and in practice. One-hundred years since women in the UK voted in a general election, curator and writer Libby Sellers framed the second day with some uncomfortable statistics: 75% of design students today are women, but only 25% end up in senior positions in the industry.

First up, Women at School. Is our design education system to blame for this disparity? Catherine Ince, senior curator at V&A East, shared her research on the Bauhaus, which is also celebrating its centenary next year. Similar to contemporary statistics, more women thank men applied to the Bauhaus when it opened in 1919, but very few women designers from the school’s 16-year history are remembered and recognised today. Ince described an institutional culture that pushed women towards ‘feminine’ crafts like pottery and weaving, based on a belief that women inherently thought in two dimensions rather than three.

Exhibitions and publications are helping to return women designers to ‘3D’, so to speak. Bauhaus graduate textile designer Anni Albers is now having her first major retrospective at Tate Modern, and is just the tip of the iceberg of women’s work now being rediscovered, with Libby Sellers’ book Women Design: Pioneers in Architecture, Industrial, Graphic and Digital Design from the Twentieth Century to the Present Day, also published this year. The panel described progress as being circular, requiring constant revisiting and reframing.

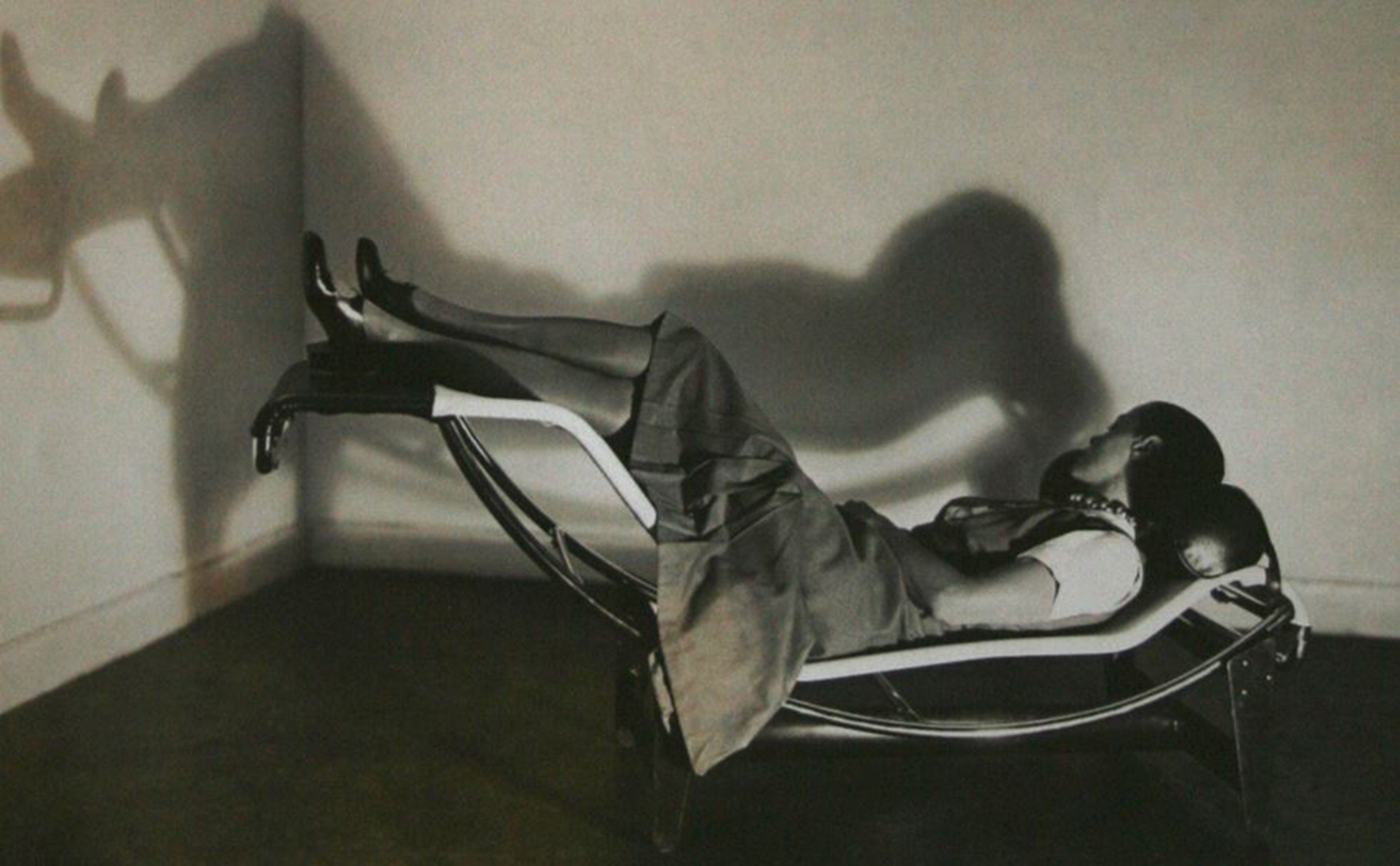

Another interesting debate was around the characteristics of feminine and masculine design. Is this really a thing? Ray Eames was mentioned as an example of feminine design practice with her focus on research, writing and analysis. Penny Sparke, professor of design history at Kingston University, speculated that in the near future women designers will become more prominent out of necessity, suggesting that collaboration and adaption – which she defined as inherently feminine design instincts – will be essential in tackling important issues such as climate change.

I pondered this in the short break that followed, and it was only as I joined the winding line to the women’s bathroom that I registered how lopsided the audience was. Whilst unsurprising, it was disappointing and made me question the day altogether: doesn’t this subject need to be discussed in the mainstream?

Back from the break. Teacher, curator and editor Shumi Bose introduced the second series of talks, Women, Design and Geopolitics. Interestingly she revealed her own resistance to participating in these kinds of ‘women-focused’ events. She confessed real discomfort in the idea that her ‘qualities’ as a young women from an ethnic minority may have afforded her certain professional opportunities instead of her abilities.

In the presentations that followed, architects Lina Bo Bardi and Minette De Silva, and textile designer Althea McNish (a new discovery for me) were affectionately described as anomalies of their time, using their own qualities of difference to their advantage, in one way or another. In the conversation afterwards, Bose remarked that she had become more accepting of her own ‘box-ticking’ qualities, after a young student had personally thanked her for being an alternative role model. An important step towards parity is to have visible ‘exceptions to the rule’ for others to look up to.

Lunch followed, and I stepped out of the Design Museum with a friend. Over soup, we discussed the conversation so far. Was the ticket-price a reason the audience was so limited? Was the discussion too gender normative? In the process we managed to miss most of In Practice with writer Emily King, and graphic designers Frith Kerr and Marina Willer. On our return, the practical reality of child-raising was the subject at hand, specifically the role maternity leave played in promoting gender pay gaps.

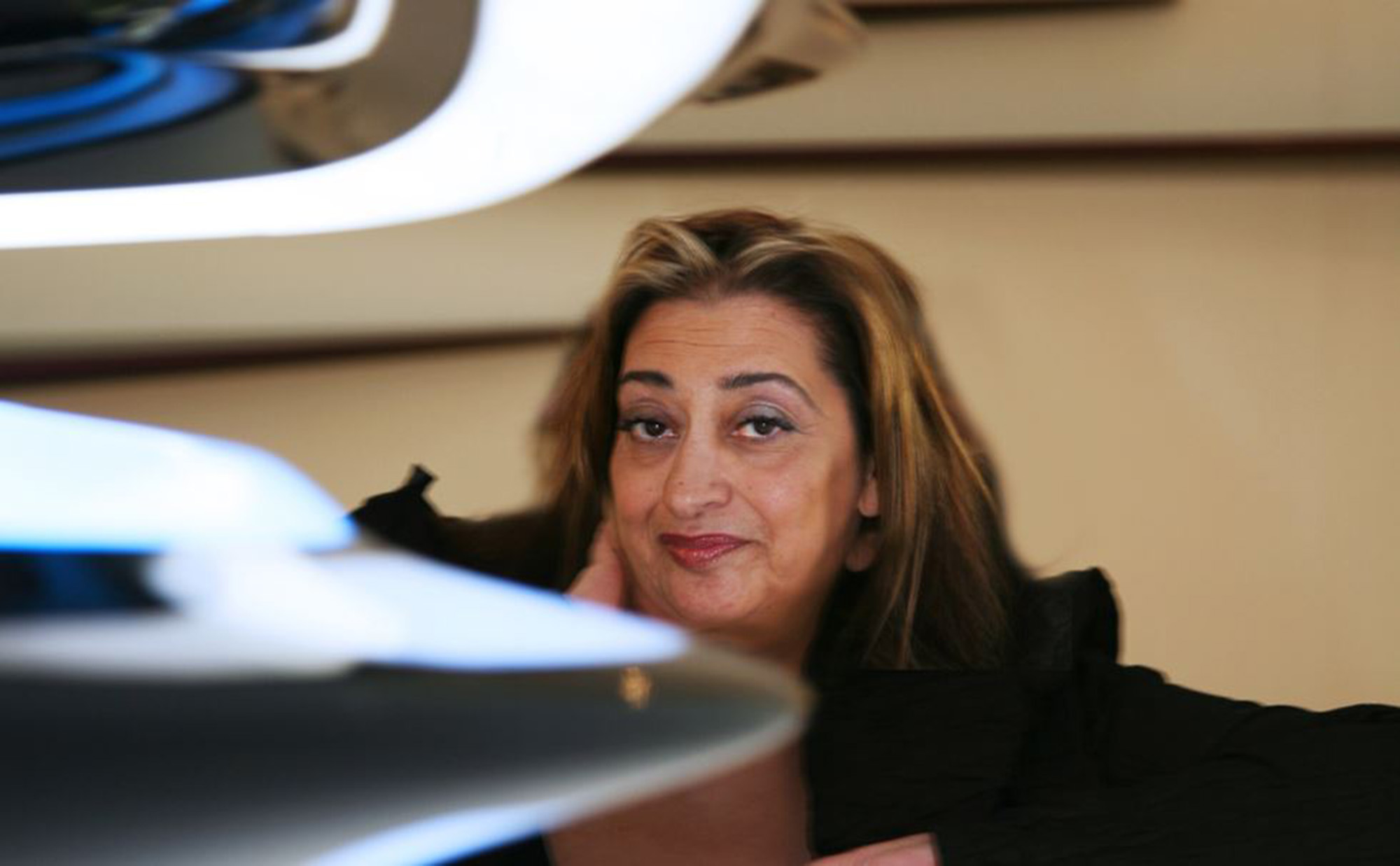

The day finished with Self Belief, a call-to-arms from architects Farshid Moussavi and Odile Decq. Part of the VOW (Voices for Women) collective behind the Women’s flash mob this year at Venice Architecture Biennale, they spoke openly about their personal frustrations working in architecture. Both admitted to experiencing professional ostracisation and client skepticism when they shifted from working with their partners to solo practice, and discussed how difficult it was to be assertive in the workplace without being perceived as ‘hysterical and complicated’. Moussavi talked about her previous employer, Zaha Hadid, as someone who was successful by ‘being herself’, not worrying too much about how others regarded her. She went on to suggest that this is what we should aim for – a professional culture that celebrates difference and plurality of all kinds, in gender, race and class.

Perhaps this is a useful lens to make women in design more universal? It is of course not only women who have low-representation in design; the design industry as a whole would benefit from greater accessibility. I left the Design Museum musing on the 1918 milestone that had framed the 2-day programme of talks. Whilst a select group of privileged women gained the vote 100 years ago, it took a while longer before all women (or men) were afforded the same right in the UK. We have a rich selection of pioneers to draw inspiration from; now let’s work harder for a design culture that allows us all to ‘be ourselves’.

A warm thank you to Kate, our London woman on the ground. All the images in this article are provided courtesy of Design Museum. Women Design took place on 7-8 December 2018 at Design Museum in London. Kate Riggs works with writer Stephanie Guest to unpack architecture and space through subjective narratives – you can find out more about their work at guestriggs.com.