Discovering new politics of music in Montreal

In 2014, little signs began to appear on lampposts around Montreal, where I live. They carried a short message in French, the city’s dominant and official language, ‘LA NUIT, LE BRUIT NUIT’, which translates roughly into English as ‘At night, noise is a nuisance.’ The poster flattened and shaped the ‘U’ of NUIT into a half moon, bringing an element of playfulness to what was otherwise a sharply-barked official warning. In the same year, I found signs in trendy neighbourhoods of Paris, France making similar points, though in wordier fashion. One set ‘Chut!’ (French for ‘Shh’) and ‘Silence!’ atop a long list of synonyms for quiet, ending with a plea to readers to find ways of living together.

Nothing in these signs made specific reference to music. Their messages, however, are slogans in the battle over music unfolding in the fashionable, gentrifying areas of contemporary cities. Clearly, the intended audience for these slogans is not street workers starting up their machines at 6am, but musicians playing too late or their audiences gathering outside venues to socialise in groups. In this new battle over night and noise, the politics of music is being redefined with a new urgency.

The question of how music might be political has a long history. Music has long been a form of political protest, or a vehicle to express anger, misery, oppression and marginality. If music has always been about communicating a message, it is now, in crucial ways, about protecting or making space.

Important innovations in music, from the 20th century onwards, have worked to transform music’s relationship to the environments we live in. Eric Satie’s Furniture Music, like Brian Eno’s Ambient Music or the late 1990s Loungecore movement, all embraced music that receded into the background, blending with the gentle atmospheric sounds which surround us all the time. “How hard should listening have to be?” was the provocative, yet laid-back question posed in the liner notes to the 1995 CD compilation The Easy Project: 20 Loungecore Favourites.

Just as often, however, music has laboured to burst out of its environments, making us confront its disruptive force. Music that is noisy and difficult tries to take its place amidst the loud noises of cities, factories and traffic, mimicking those noises (as did the industrial music of the 1980s or 1990s) or at the very least capturing some of their unsettling power (which is one of the reasons why drum ‘n’ bass and all its tributary genres seem quintessentially urban).

In 2018, the question of music’s relationship to environments is less about designing music appropriate to them. Rather, music has become political in a much more basic sense, reduced to the status of brute noise and controlled as such. Forms of musical expression that were not overtly political now find themselves part of broader struggles over urban change. We are no longer in a battle over the acceptability of certain kinds of music, of the sort that marked the early days of rock ‘n’ roll or rave/techno. Rather, music offends when it is reduced to its basic sensory matter, when it is seen as simply disrupting the quiet of the urban night.

In cities around the world, a new politics of music has taken shape in response to neighbourhood gentrification. The effects of rising real estate prices on music are at least threefold. Musicians, like other artists, are moving out of inner-city neighbourhoods in response to rising rents, breaking up the older ecologies of music-making that once marked areas like the Mile End neighbourhood in Montreal. At the same time, music venues are closing as rents are raised, and as property owners opt for the more profitable alternatives such as restaurants, or drinking establishments that the French call bars à ambiance musicale – where music is a festive, but not overly intrusive backdrop to drinking craft beers and conversation in mid-evening. These developments caused the recent closing in my neighbourhood of Cagibi, a vegetarian restaurant and music venue that had nourished successive waves of musical invention.

The changes just described have affected other cultural venues, of course, like repertory cinemas and bookstores, who face the additional challenge of internet distribution of the cultural products on which their economic viability depends. The third effect of gentrification targets music more specifically. Music is challenged by the movement of young professionals into inner cities – drawn at first by the signs of edgy culture, but soon finding that the noise of music clubs and the buzz of conversation by those gathering outside them is disrupting their sleep and, increasingly, that of their newly arrived children. Divan Orange, a live music venue in Montreal that has hosted 10,000 acts in its history, finally succumbed to closure, the result of receiving exorbitant fines on a regular basis for ‘excessive noise’.

Montreal is often compared to Melbourne – both are musically rich cities with significant student populations. Montreal has a long history of night-life entertainment, stretching back to the 1920s, when the prohibition of alcohol in the United States sent people north to drink alcohol legally, fuelling the growth of a vibrant sector of dance clubs and music performance venues. In the 1970s, as I have shown elsewhere, Montreal’s clubs and dance music record labels made it the second city in the world for disco music. By the early 2000s, the city was dubbed the new Seattle, home to an independent rock scene that, with bands like Godspeed You! Black Emperor and Arcade Fire, took shape in neighbourhoods where rents were low and available large spaces were perfect for band rehearsals and performance. This century-long record of international success is scarcely mentioned in the city’s promotional materials, which emphasise the packaged heritage appeal of Montreal’s Old Port or the enticements of its Underground City (in reality, little more than a string of interconnected shopping malls and transportation hubs).

Montreal, like most North American cities, is behind most of Western Europe in devising policy to address confrontation over music, noise and the night. Some of these instruments, like the appointment of Night Mayors or Night Czars to mediate between nightlife sectors and city governments, are easily dismissed as gimmicky, but they create spaces of consultation in which the night time music sector may make its concerns heard. In France, ‘Night-time Charters’, which bring neighbourhood residents, business owners and artists together to resolve their differences, have been implemented in several cities.

Montreal lags behind Melbourne in acknowledging the vitality and significance of its music scene. In 2018, the Canadian Chamber of Commerce issued its Music Cities Toolkit, a set of guidelines which cities across the country might use if they want to become ‘music cities’. Municipal governments were advised on how to highlight their musical activity to promote tourism and strengthen the economic health of this creative sector. This recognition of music’s contribution to the life of Canadian cities was welcome and a long time coming, but it seemed to arrive too late. The battle for music was already being fought night after night, in the moves by developers to close longstanding music venues (seven in Toronto in the first three months of 2017) and in the steady stream of noise complaints that made any planning of musical events almost impossible.

Night is a time, not a space, but in cities around the world it is more and more viewed as a territory, with its own inhabitants, customs and forms of belonging. In his book La nuit: dernière frontière de la ville (Night: the city’s final frontier) the French geographer Luc Gwiazdzinski speaks of the ways in which, across the 24-hour cycle of day and night, city dwellers experience a ‘discontinuous citizenship’. Some city-dwellers are more welcome in the night; others, like women, the elderly, or youth of colour, face heightened harassment. Others still, like those seeking spaces in which to dance, play or listen to music, invite an uneasy suspicion which inclusive, thriving cities must learn to overcome.

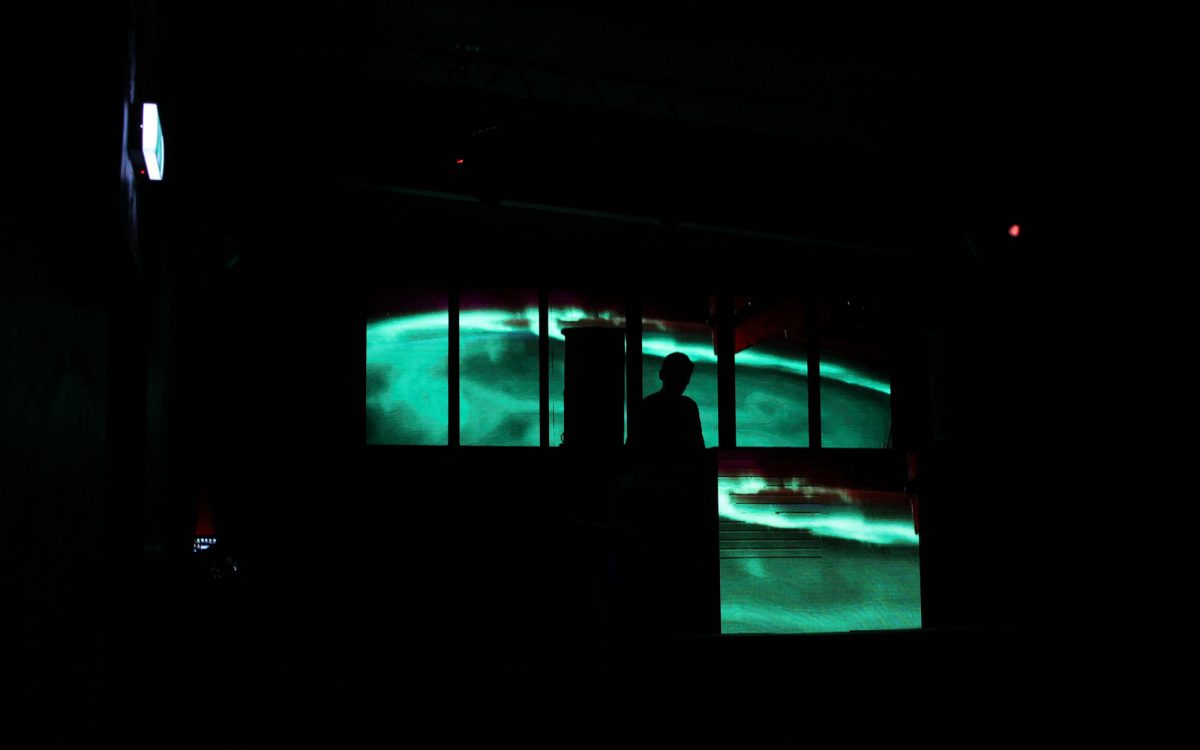

Thank you, Will, for a valuable contribution to the discussion about cities and nightlife. Many thanks also to our amazing photographers George Staniland and Alex Lama, for two takes on Melbourne’s music culture and spaces. To learn more about night culture around the world, visit Will’s blog The Urban Night.