Preserving cultural heritage at Kyudōkaikan in Tokyo

Until 1853, Japan was deliberately closed off from Western influence. Western technologies such as the railroads, plumbing systems, even glass windows, were either unknown or ignored. That all changed when Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) triggered one of the most rapid periods of modernisation in history, across all areas of life, from medicine and architecture to art and science. The Japanese Empire sent educated men on study tours to learn about Western science and systems of knowledge, and how they could be adapted to the Japanese context. New materials created new possibilities: for the first time, buildings in Japan were being made using concrete, bricks and glass. Suddenly exposed to a variety of influences, the architects of the time were combining wholesale elements of both cultures into unconventional combinations – reflecting the incredible speed of learning that characterised Japan’s early modernisation.

The Kyudōkaikan [‘Hall of Pilgrimage’] stands out in the quiet backstreets of Tokyo. Incongruously church-like and stately, generously set back from the street, its red brick and aged concrete looking at once old and imported. It was once a renowned school for students of Buddhism, dating to a time when Japan was much more religious than it is today. The history and architecture of the building itself mirrors the changes that took place in Japan, and the story of its renovation hints at a path forward for a country full of incredibly old history, and yet relentlessly modern.

At the tumultuous beginning of the Meiji era in 1868, many of the nobles who had been allied to the emperor returned to their home provinces. They had been forced to build compounds in the city for their family members in a near hostage scenario, and at the end of shogunate there was no need for these to be maintained, so the grand estates were broken up and sold off, or appropriated by the government for other purposes. You can still see the line of the old imperial moat in a ring-like canal circumnavigating the palace, and a road, the Sotobori-dori. Beyond this moat were housed various estates, military barracks, storehouses, and administrative facilities. When that land was abandoned and put up for sale at the beginning of the Taishō era (1912-1926), Chikazumi’s grandfather, a Buddhist monk, acquired a small parcel to start a school and temple. He subsequently bought some neighbouring parcels and commissioned a young but accomplished architect named Takeda Goichi to design him a worship space that could also be used for education, as well as dormitories for the acolytes.

This was a turbulent time in Japan; the country was opening itself to the world and sending emissaries abroad to learn about technology, science, and culture. Japanese woodblock prints were influencing French artists and helping to form the Art Nouveau movement, while Japanese academics were picking up German medical journals, English architecture books, and French civil engineering methods. In this era of cross-pollination, Takeda Goichi travelled to Europe and America. The influence of his travels would show up in many of his buildings, which seem to be based firmly in a Western idiom and yet grasping for new expression in the decorative facades, and in the peculiar expressive flourishes, such as in his work on the Kyoto Town Hall.

His was the generation of architects that would become known for really mastering Western architectural techniques and giving them their first strokes of local character. This was the generation that would teach Kenzo Tange, whose own contemporaries would develop a truly modern Japanese aesthetic using Western construction techniques and materials.

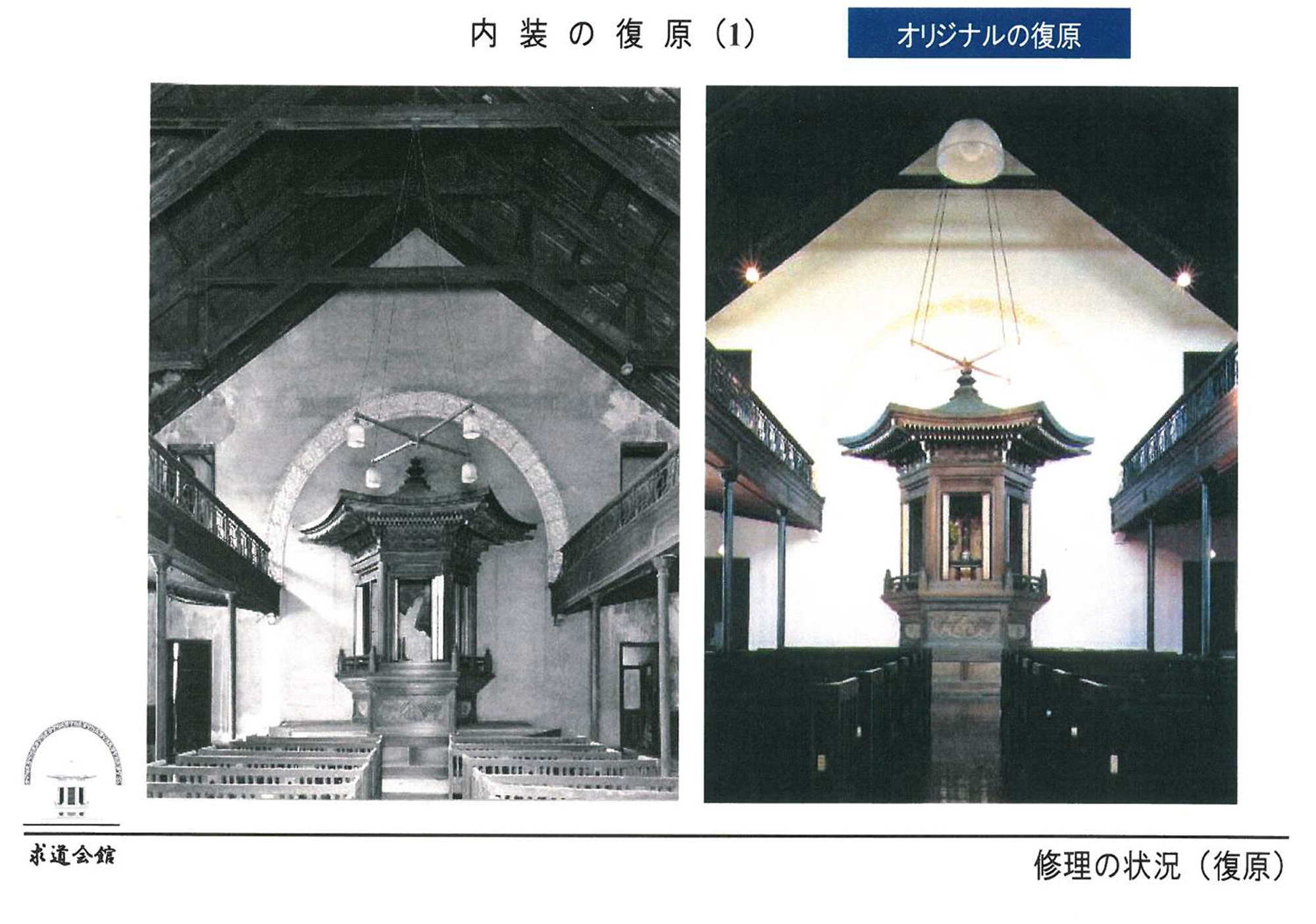

While on a trip to the US, Takeda Goichi had seen the characteristically simple Protestant churches and been taken with their unvarnished look. He had also come across truss-and-frame techniques which were used for warehouses and other utilitarian structures of the time. The trip must have influenced his ideas heavily, because when he was commissioned by Chikazumi’s grandfather to design the Kyudōkaikan, he took the warehouse trusses, the church layout, and amalgamated them into a Buddhist space of worship and learning.

On his travels Takeda had also learned about the new technology of reinforced concrete. Curiosity led him to use it for the construction of the student dormitory to the rear of the property, as well as the four front columns of the main hall, as an experiment. Those columns would later need extensive reinforcing and stabilizing beams added, but the dormitory building has lasted quite well and is now the oldest occupied concrete domicile in Japan.

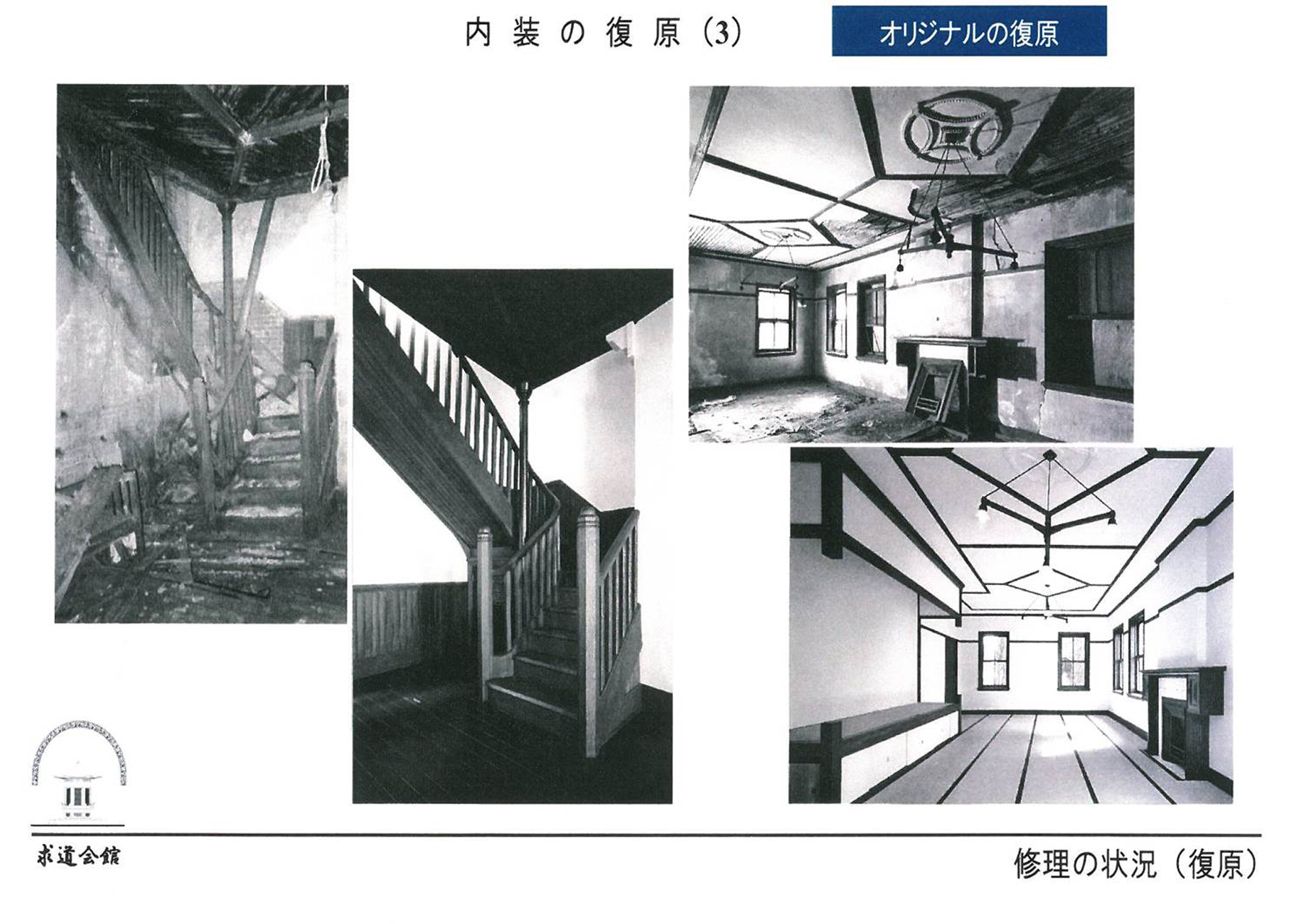

In the years between 1915, when the building was completed, and 1996, when Chikazumi began to plan the rehabilitation, time and weather had wrecked much of the structure and ornament. The roof had collapsed and rain had swelled and soaked the plaster and timbers. The rebar had rusted and popped off chunks of concrete, bricks had lost their mortar, and the building was in real danger of being completely lost.

“The building was costing so much money in upkeep that it was unsustainable,” Chikazumi told me during our study tour of Kyudōkaikan. “If we kept going like that we would have had no choice but to sell it to some developer who would just make more typical apartment buildings.”

Chikazumi contacted the builder who had originally built the structure 80 years before. Toda-gumi had become Toda Corporation, and gone from making wooden temples to steel skyscrapers and huge infrastructure projects. Nonetheless, they agreed to complete the renovation. However, with all the damage, it was an expensive proposal. The Japanese government was not able to fund much of the cost, even though the building received heritage status – the number of heritage-listed buildings in Japan far exceeds the government’s ability to fund their upkeep and repair. Private money would be needed to pay for the restoration of this unusual building which in so many ways encapsulated Japan in the Taishō era.

But Chikazumi saw an opportunity in the disused student dormitories, which had been vacant for years. The last tenants must have been getting rather cheap rent, living in a decades-old dormitory behind the slowly collapsing husk of the hall – but the building itself was sound, and for unknown reasons, Takeda Goichi had copied the floor-to-floor dimensions from the Western concrete buildings he had seen, so the dormitory had very high ceilings which could be renovated nicely. The corridor was also quite wide and, by combining several dorm rooms together as well as their corridor, Chikazumi was able to design some very attractive apartments. In addition to the design and construction management, Chikazumi arranged leasing agreements with tenants, which would pay for the annual costs of upkeep as well as help fund the construction.

“This was about preventing the loss of old Tokyo’s atmosphere as much as preserving a historical building,” says Chikazumi, with a protective look out the window. By turning some of the property over to private apartments, and preserving the hall and the grounds, an exceptionally rare set of residences was made. For the people lucky enough to live there the Kyudōkaikan apartments are spacious, high-ceilinged, customizable, and well located in a green and spacious block of the city.

Meanwhile, an important part of Japan’s cultural heritage has been preserved through private action, and for Chikazumi this may be the most important legacy of the project. “The people in charge of historical preservation in Japan need to think more creatively and look for new models,” he said. “It’s my hope that this project proves to them that it’s possible to pay for preservation even when there is not enough government funding.”

In a country with so much history and yet so relentlessly modernized, this is an acute question. In the rush to develop economically, much of the architectural heritage of Japan was lost in the unprecedented growth of the 20th century. While many temples and shrines have continued to operate viably, and remain a center of community festivals and rituals, many older buildings and pieces of infrastructure have been lost. Unless a new business model can be found, or the government decides to radically increase funding, the country will continue to lose more of the physical remains of its past. What the Kyudōkaikan represents is another way forward, in which passionate individuals can make new business models for old places, and in doing so make sure they find a place in the modern world.

Thank you, Chikazumi-san, for taking the time to tell us about the restoration of your family’s temple. Many thanks also to Toda Corporation for sharing their notes about the reconstruction. Arigatō gozaimasu!