AP x Liquid Architecture: Eavesdropping

From Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England (1769): ‘Eavesdroppers, or such as listen under walls or windows, or the eaves of a house, to harken after discourse, and thereupon to frame slanderous and mischievous tales, are a common nuisance and presentable at the court-leet’.

When the old common law offence of eavesdropping was first codified in ‘The Commentaries on the Laws of England’ by William Blackstone, it was concerned with public order, stopping people from spreading gossip by listening through the thin walls of village houses. Today, the word is associated with big data, surveillance and privacy concerns. Eavesdropping is a collaborative investigation by Liquid Architecture, Melbourne Law School and the Ian Potter Museum of Art into the contemporary conditions both of listening and being listened to: who is listening, to whom, why and with what effects? Artists such as Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Susan Schuppli will present works alongside artists who are incarcerated on Manus Island.

The winter EARS mix has been created by Sam Kidel, a sonic artist and researcher from Bristol who is concerned with the politics of sound and listening.

According to Kidel, the framing of ‘voice’ in ‘voice recognition’ can tell us something about the way that persons are conceptualised and captured in auditory surveillance. “Fred Moten said in an interview that he always thought that ‘the voice’ was meant to indicate a kind of genuine, authentic, absolute individuation, which struck him as (a) undesirable and (b) impossible”, Kidel recalls. “Similarly, Robin James tweeted some reflections on voice recognition technology, and the way the design of these technologies highlights how ‘liberalism uses voice as a metaphor for personhood, which it always has constructed as a power relation over non-persons’. Both Moten and James indicate alternative possibilities for framing that which we refer to as ‘voice’.”

In this mix, ‘Unsettled Voices’, Kidel tries to follow Moten and James in orienting our ears away from the coupling of voice and personhood. “I focus on what’s unsettled when voices are heard as sound, when voices sound like machines, when voices are heard from those framed as non-persons, or when voices are untethered from personhood entirely,” he says. “I created the mix as a tool for feeling into unsettled experiences of voice.”

EARS #33: Unsettled Voices, tracklisting:

Trevor Wishart – Globalalia (00:00)

Neural Network generated “English” Voice using RNN/LSTM (4:04)

WaveNet speech generation trained without text (4:43)

Hecker – A Script for Machine Synthesis (5:38)

Kepla and DeForrest Brown Jr – Crowding and Bubbling Landscapes of Deposited Bodies Suite I (12:20)

Kepla and DeForrest Brown Jr featuring Embaci – Lost My Head (14:32)

Holly Herndon – Dilato (15:30)

Laurel Halo & Hatsune Miku – Until I Make U Smile (21:52)

Lotic – Banished (27:45)

Maja Ratkje – Breathe (30:28)

David Dunn – Mimus Polyglottos (35:37)

AP: What does eavesdropping mean in the context of this series?

Joel Stern: The animating question for us was ‘can we develop a working definition that captures some essential qualities of eavesdropping?’ A definition that can move across disciplinary boundaries [law, art, political contexts] and be expanded to include things that might not immediately come to mind.

James Parker: As a legal academic, I’m really interested in the social and legal histories of the eavesdropping offence described by Blackstone. To me, it’s really important to maintain a certain scholarly fidelity in this project: to think seriously about what it meant for eavesdropping to be a real social problem and in that very specific way in, say, 14th or 15th century England. As a (first time) curator, I also wanted to be unfaithful though, and look at eavesdropping as more than just a legal term, a concept with a life of its own, that could be appropriated or expanded somehow. Rather than eavesdropping always being a malicious listening, for instance – being eavesdropped on by the state or the corporation – what if we were to listen-back? Eavesdrop on the state, say, as an activist listening practice? Or what happens if you accept eavesdropping as inevitable in a certain sense: as essential features of sound and listening themselves?

AP: How is listening framed differently here, compared to other Liquid Architecture events?

JS: Traditionally, Liquid Architecture is interested in the problem of how to define sonic art and speculating where it might be headed. There have been a lot of opportunities for artists who meticulously produce sound to have their works heard in galleries and museums. This is a shift from focusing on the production of sound to focusing on the politics, circumstances and context of listening. The challenge was in bringing together a suite of works that articulates a politics of listening.

JP: Lawrence Abu Hamdan and Susan Schuppli from Forensic Architecture are two artists who have been central to our thinking about the show. Lawrence and Susan are both interested in sound and law together – a very politicized understanding of law, not simply law as the decider of what’s legal or illegal, but as a forum in which political questions are litigated. All their artworks intervene in legal debates in some way. For example, Lawrence has developed an idea of ‘forensic listening’. He makes artworks where the central methodology is grounded in forensic techniques from the law, particular ways of engaging with evidence. For example, one of the works in the show is about Saydnaya prison in Syria, where around 15,000 people have been killed. It’s a silent prison, where to speak or even whisper is literally a matter of life and death, and he has interviewed survivors and asked them to describe their sonic experiences. The earwitness testimony presented in the work focuses on the role of sound and silence at Saydnaya both as evidence of the violence enacted there and, as Abu Hamdan puts it, ‘a form of torture in and of itself’.

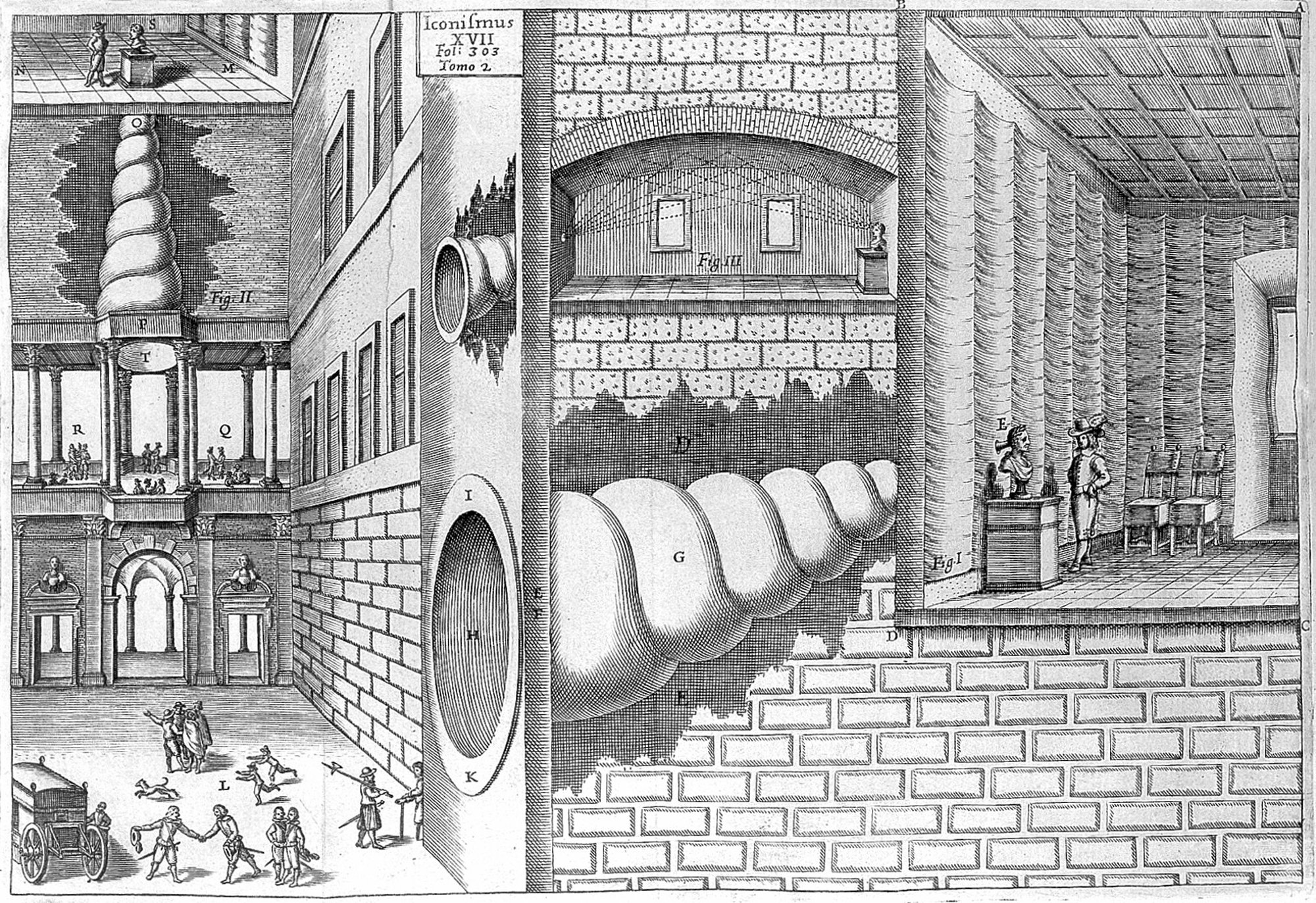

AP: Can you take us through the Blackstone’s definition of eavesdropping?

JP: There are a few interesting things about the definition that seem odd from a contemporary perspective. First, eavesdropping there is architectural – whereas now we think of it as more technological. In the offence described by Blackstone there is always a distance between the eavesdropper and the person being listened to. There’s already a sense of walls and windows, a visibility that is there from the start. Originally, eavesdropping was a public order offence; it was about disrupting social order, not privacy, which is a much more recent concept. The focus on gossip is particularly interesting in this respect. It almost makes me think of ‘fake news’.

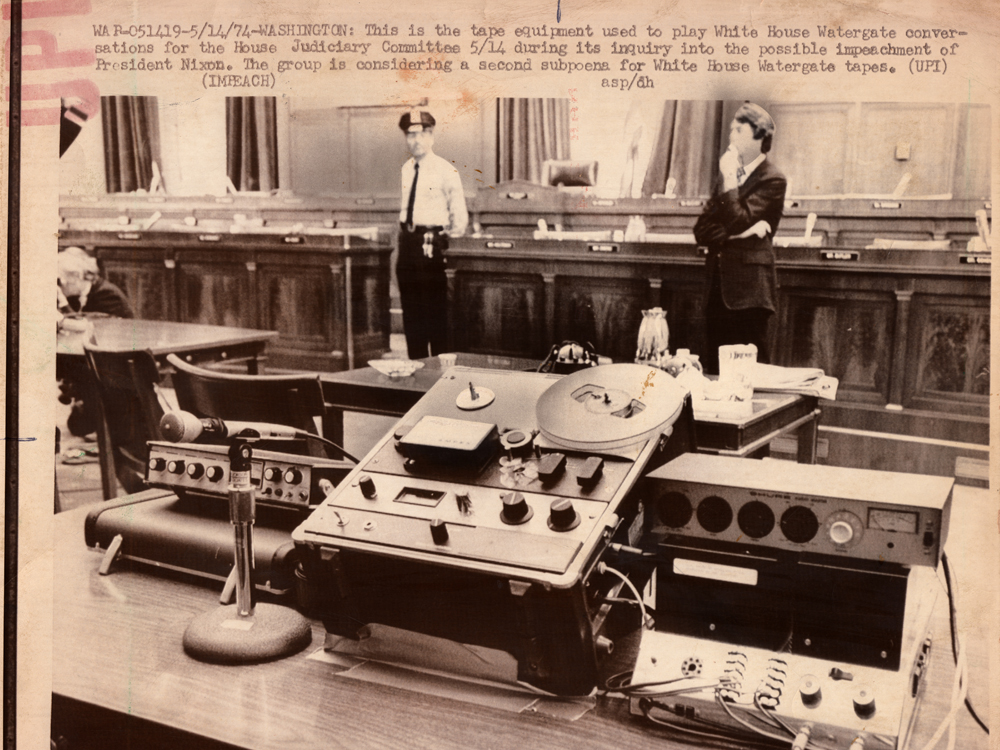

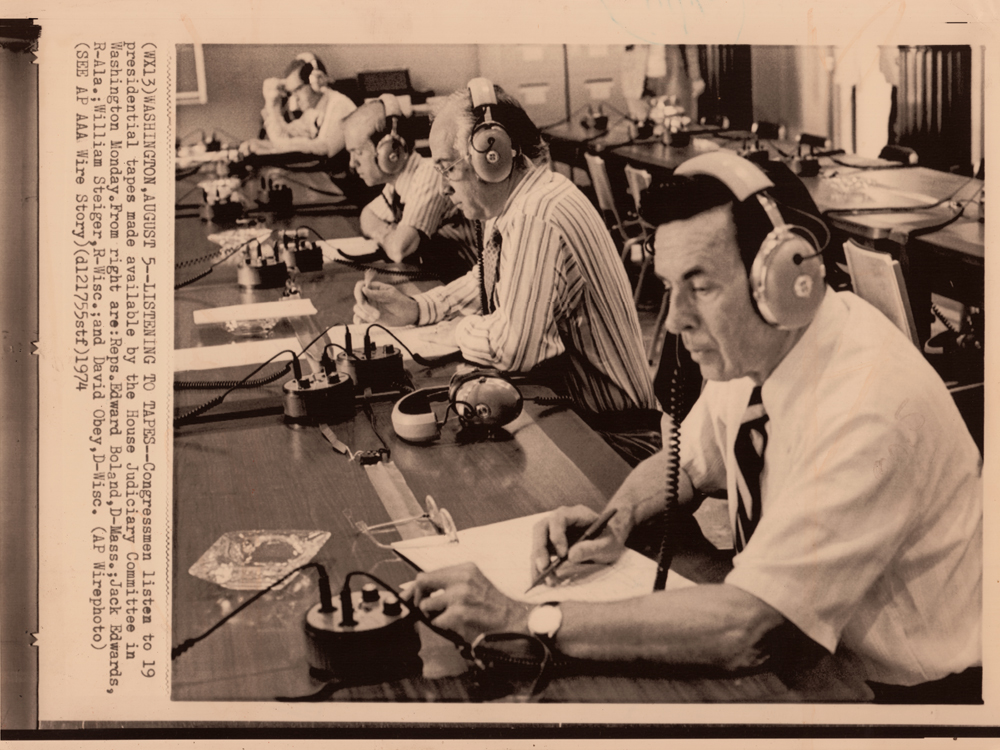

AP: Now eavesdropping transcends physical space. What was the impact when eavesdropping became about recording, as opposed to listening out for voices under an eave?

JS: As the artists and academics came on board this project, one of the things that emerged was how certain technologies become paradigmatic in the shifts of meaning of the term. Probably none more so than the telephone; and the telephone is just a microphone embedded in a transmission device. Listening became networked in a way that it wasn’t with telegraph wires.

JP: Many artists deal with telephones – not just smartphones – in one way or another. The transition of the main object of eavesdropping from a wall to a telephone begins at the end of the nineteenth century, when the telephone was invented. There was some wiretapping of telegraphs, but it became a huge issue with the tapping of phones. Although – for a long time, it was presumed your phone calls were being listened into because the phone networks were very local. And the operator was not hidden. You called an operator who patched you through to the person you wanted to call.

AP: Our attention is so divided now. Has the fragmented way we move through our environment informed how you’ve gone about putting this program together?

JP: In terms of gallery attendance, yes, I think so. There’s something a bit authoritarian about the way we’re going to organise the show: ‘if you want to listen, you must listen this way’.

JS: We’re invoking a few different forms of listening modalities or listening movements, which are supposed to draw attention to how you, as a listening subject, are structurally implicated with what you hear. We outlined some of those movements as clusters under which to group certain works: Overhear, Listen Back and Earwitness. With each of those movements we’ve tried to emphasize a different condition of listening and ask the listener to deal with, or listen, through the prism of a certain kind of question. They’re deliberately slippery terms. With Overhear, we are talking about what you hear unintentionally by virtue of having ears and a lack of control over the sounds that reach you. But we also think with Overhear as an excessive sort of hearing, too much hearing.

JP: Listen Back is meant to be a kind of activist listening or reversing the directionality of the eavesdropping. For example, the act of listening to somebody whose voice may not ordinarily be audible: listening to the guys on Manus, or listening through history.

JS: Yes, listening back can definitely be understood in an archival sense, as a re-listening to earlier artifacts. In re-listening to them, we might have a radically different understanding of what they are. Finally, the Earwitness idea has been a really productive one for us: a listener who bears witness. There are certain responsibilities that come with that – to question truth, or question evidence etc. What are the responsibilities of the earwitness, as opposed to someone who is simply listening for entertainment, or for stimulation, or pleasure?

JP: This show is definitely not about beauty in the traditional sense. The sonic works that we’re interested in are troubling. There’s a heavy conceptual and political-legal dimension; they all gesture at something which is not sound. They all put sound and listening in social worlds. One of the works is about the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence, the relation of human to non-human. This is not just about aesthetics. Or, you might say, it’s about how the aesthetic always has to do with the social, political, and even the legal too.

A big thank you to Joel and James for being so generous with their time on this interview, and to Sam Kidel for the mixtape. The ‘Eavesdropping’ exhibition will run from 24 July through to 20 October at Ian Potter Museum of Art, with events at MADA, Howler, Sydney Opera House, UNSW Galleries, and Institute of Modern Art in Brisbane. All details here.

Tuesday 24 July 2018 – Sunday 28 Oct 2018