Paola Balla on curating a Blak matriarchy

When Max Delany, artistic director of Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), invited Paola Balla to curate an exhibition of Aboriginal art in 2016, it was the first such undertaking for ACCA in more than twenty years – and a resounding success.

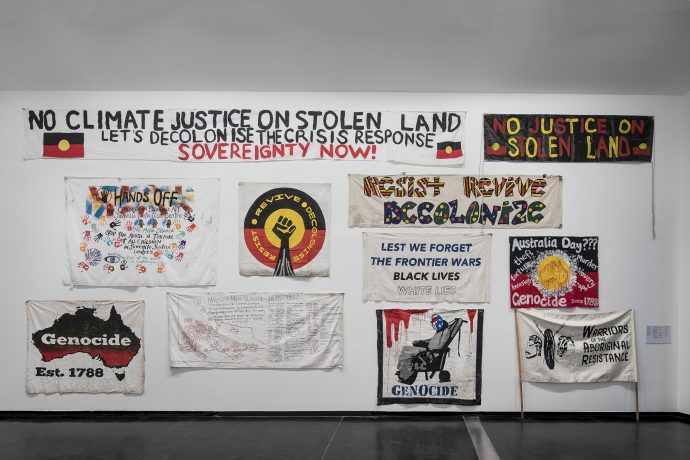

Effortlessly bringing together vernacular and collectable art, drawing connections between historical artefacts and contemporary hip-hop from Shepparton, and making an expansive point about the continuity of Aboriginal life in Australia, Sovereignty captured the zeitgeist of a woke year.

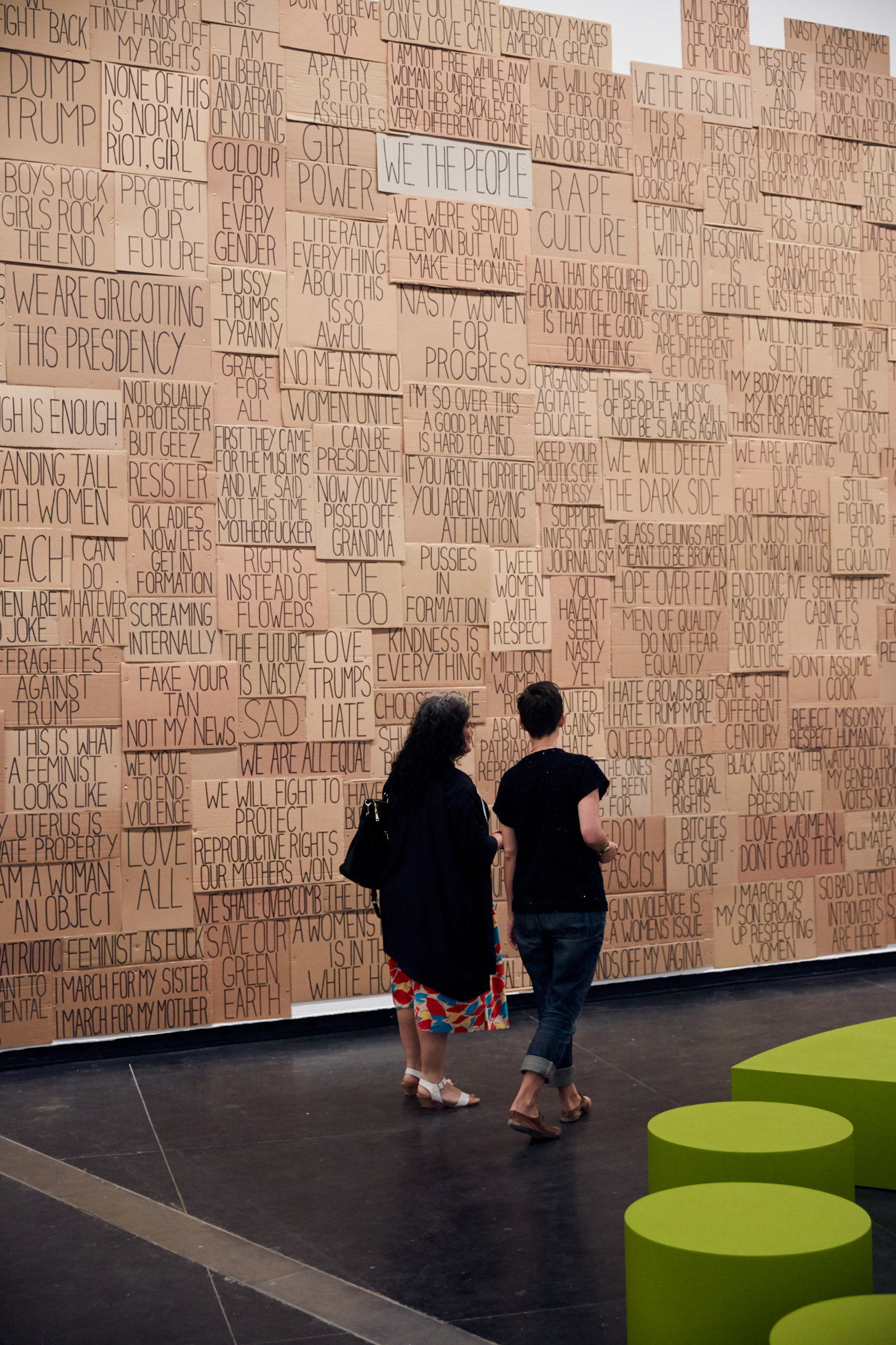

Paola Balla, a Wemba Wemba and Gunditjmara artist, curator and researcher with strong links to the local arts community (she founded the Indigenous Arts and Cultural Program at Footscray Community Arts Centre), emerged as a voice of contemporary Aboriginal feminism – or matriarchy, as she prefers. Hers is a voice grounded in lived community history, but informed by an expansive dialogue with global First Nations scholarship. One year later, Balla returned to ACCA to co-curate Unfinished Business: Perspectives on art and feminism (15 December 2017 – 25 March 2018), a survey of Australian feminist art. Her contribution remains as simple as it is profound: to remind us that Aboriginal families’ experiences cannot be understood outside of the historical loss of sovereignty, and that this trauma has all too often been carried by Aboriginal women. “Don’t let your racism drive your feminism,” she often says, quoting Arika Wauulu from Real Blak Tingz Collective, one of the founders of Warriors of Aboriginal Resistance.

Jana Perković

For many years, I did an exercise with my students at the Victorian College of the Arts where I would say, “Who here identifies as white? Hands up!” And then I’d ask, “Now make your case: what makes you white?” They were put on the spot. They would say, for example, “My family is Italian. My parents are not white, but I am, because unlike them I didn’t get bullied at school.” They instinctively knew that race was relative, that whiteness is a kind of points system.

Paola Balla

One of the main things my Indigenous colleagues and I have to work on with people is their whiteness. You’re not here to learn about art, to learn Aboriginality, if you don’t understand yourself first, and the invisible privilege of whiteness, which is so normalised in this country. They think ‘Australian’ equals ‘white’.

My husband often pushes his students. They will say, “Oh, I’m just Australian,” and he’ll say, “What does that mean?” They think we’re being offensive. Well, I am proud to say I’m black. I know what blackness means. Tell me what it means to be a white person. They often can’t tell you, they can’t articulate whiteness much beyond a notion of racial superiority, and they really struggle when you push them on it, because the invisibility of white privilege is so entrenched in this country.

I’ve been teaching my kids: when someone asks where you’re from, you ask them, “Who’s asking? Who are you to ask me that?” I think it is an innate sense of superiority to feel you have the right to ask. It’s saying: “Who are you? Do you have a right to be here? I’m going to suss you out until I can place you.”

Asking where you’re from in Aboriginal culture is a different question. It is asking: who are your people, what’s your language group, where’s your family from, who were your grandparents, your parents, which mob, which mission, which community, which Country? That’s a proper question, where you really understand something about a person. You get raised learning how to answer that question. It’s different to when a white person is asking non-white people.

JPWhat led to your involvement in curating Unfinished Business? You have spoken on numerous occasions about your unease with feminism.

PBI was conflicted, reluctant. I don’t necessarily identify with feminism. That’s not to say I disagree with the ideals of feminism and women’s rights; they are really important to me. But I identify more as a blak matriarchal feminist. I advocated for Aboriginal women to have works in the show. There was no resistance from ACCA – it was just a matter of introducing the institution to artists they didn’t know about. When people think about feminist art, they don’t necessarily think about Aboriginal women.

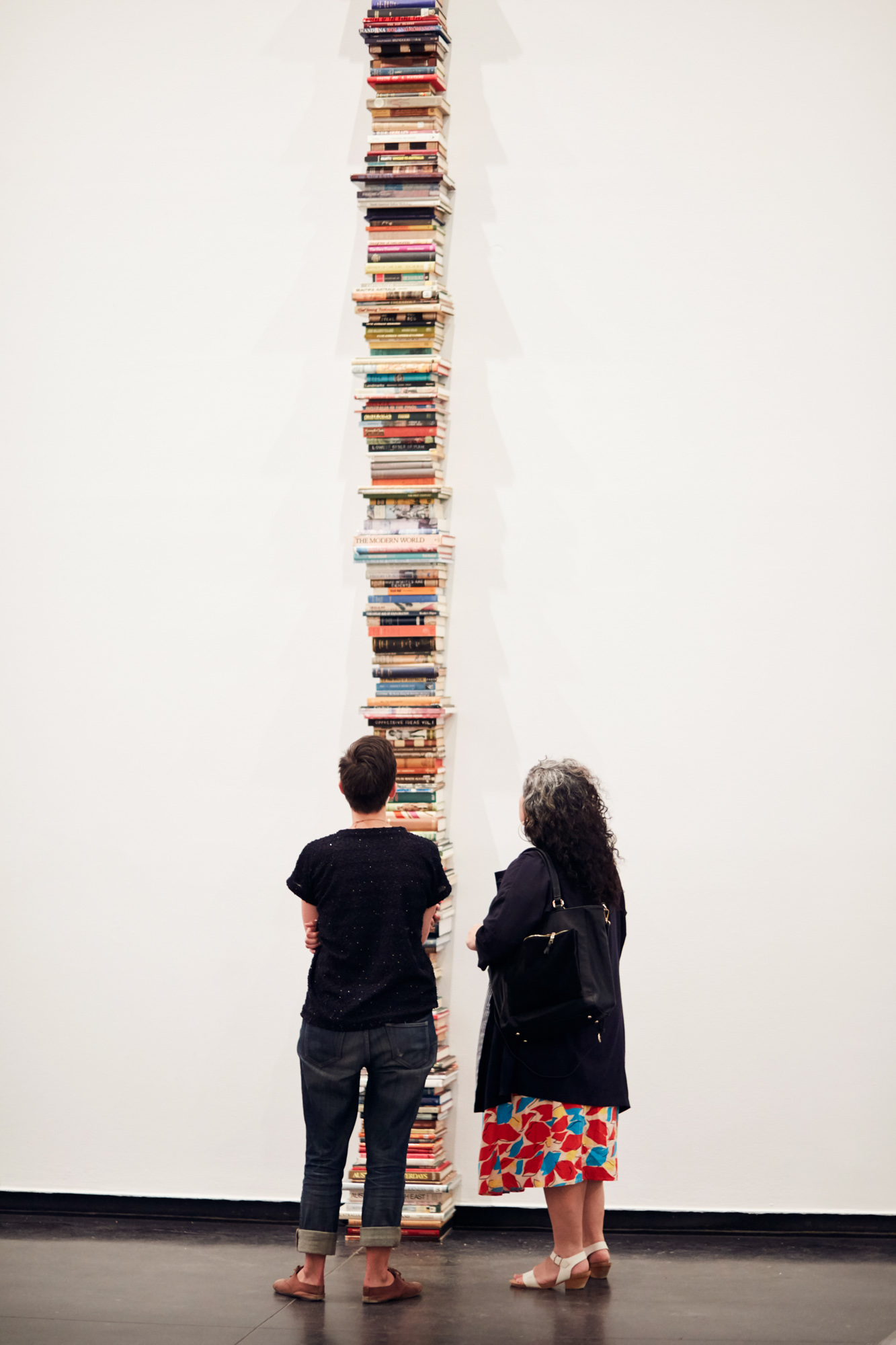

In total, there’s about ten Indigenous women and women of colour in the show. It was very important to me that they be strongly represented. One of my favourites is Racist Texts (2014) by Ali Gumillya Baker, a column of racist Australian books, from picture books to history books, spanning the height of the room. This is the first time Ali has shown in Melbourne: she is part of The Unbound Collective, based in Adelaide, in Kaurna Country – four brilliant Aboriginal women doing their PhDs.

To be invited back into a curatorial role at ACCA was really important and exciting – it was an extension of the work I did curating the Sovereignty exhibition. Often, Aboriginal curators and artists will be invited by an organisation to do an Aboriginal project, and then might never hear from them again. We always advocate for relationship development: we want long-term, sustainable relationships, not one-off projects. I believe I was invited for the knowledge I bring, but the flipside was that I knew I would be the only Indigenous curator at the table. I did think about it long and hard. I do believe in the ideals of feminism, but not white feminism as it has existed. I wanted to make sure that the blak matriarchal stamp was represented.

JPCan you tell me a little bit about the difference?

PBIt’s a bit like the T-shirt I’m wearing today, by Native American activist group RISE, which says ‘No Wave Feminism’. Anne Marsh, a white feminist academic, spoke about the notion of the waves being contested, that perhaps they are an academic construct that doesn’t exist on the ground.

Women’s authority was very respected in Indigenous culture. So many activist movements in Aboriginal culture are led by women. Women are also attacked in colonialism, through rape and removal of their children. Tony Birch, a brilliant Aboriginal author, talks about this; Celeste Liddle and many other Aboriginal feminists talk about this. Aboriginal women are the most vulnerable women in this country.

JPWould you say that white feminism doesn’t recognise that?

PBI don’t think white feminism was designed with us in mind. It was concerned with things that yes, in general, overlapped. But it wasn’t intersectional. Kimberlé Crenshaw in the US coined the term ‘intersectionality’ to talk about the intersections of race, class and gender.

JP…where, by having two problems (such as sexism and racism), you’re having a third problem, which is a lot worse than the sum total of the two.

PBExactly. Just because we might both be women, it doesn’t mean that gender trumps race. It’s not that simple. We can’t advance women when we’re not advancing Aboriginal women. At the moment, we’re the biggest incarcerated group in Australia. Our children are getting taken from their parents at a higher rate now than during the Stolen Generations. There are Aboriginal grandmothers around Australia campaigning to get children out of state care. These are women who own their homes, who have been in careers for decades, and cannot get their children out of the system.

I’ve been out to Dame Phyllis Frost Centre, which is the maximum-security prison for women in this state. I’ve done art projects with Aboriginal women there – twice. The majority of women inside have children, and they are facing arcane laws that say that, if they don’t get a job and a home within 12 months of release, they lose their children permanently. It’s a system set up to fail.

It’s heartbreaking, seeing sisters who are no different from you, [who] have just had different circumstances and choices to make. Many have experienced either sexual abuse or family violence as children, or addiction and alcoholism in the family, and the majority have experienced domestic violence in their own relationship.

We experience violence at 34 times the rate that non-Aboriginal women do and are 11 times more likely to die from that violence. This horrific tragedy is unfolding right now, in this beautiful city with all these fantastic exhibitions that I’m a part of. That’s why I make sure that every public speaking opportunity I get, I talk about these things.

JPLydia Fairhall, whom we both know through her work at Footscray Community Arts Centre, has said, “I am the first woman in my family to keep her children.” It really struck me to hear that: what does it mean on the ground, what does it mean in your community, to have a multi-generational history of children being taken away from parents?

PBIn my family, we grew up with stories. My beautiful Auntie Walda Blow told us stories about running and hiding as a child, so they wouldn’t be taken away by the authorities. There are stories in our family about where, when, how and how often the children would run and hide. Aunties and grandmothers coming down the mission road and saying, “Quick, run.” To live under that level of terrorism causes a mistrust of authorities. It causes you to become anxious about school, about welfare offices. The fear of being monitored never goes away. It is trans-generational trauma.

Only six years ago, my son had a health condition. The school didn’t believe me – they brought in a truancy officer and put us in a monitoring program. People think you have this fantastic career in the arts, you dress up and go to gallery openings, people look up to you and all that – but I am just as vulnerable as any other member in our community to having my son taken away from me, to my fitness as a mother being questioned at school. This is our reality. I am just one of so many of my cousins, friends, Aboriginal women who go through this all the time.

Aboriginal women have been depicted in the media in this country for generations as loose women, existing only for the pleasure of men. We became currency in the colonial project. But our women were also warriors, who fought in the frontier wars.

We still lead marches and protests, but at a great cost. Our women’s health isn’t good, we die at a younger age and suffer stress and heartache. It is tough, but it motivates me to keep doing this work. And that’s why I wanted to try and make sure that the Aboriginal women’s voice comes through clear in an exhibition like Unfinished Business. Because our preoccupation with women’s rights is not to bust any glass ceilings – we’re trying to get off dirt floors and concrete prison cells.

JPWhat should a white person do to learn more about this almost secret, parallel history-telling?

PBWe’re always telling our story. Auntie Margaret Tucker wrote one of the first autobiographies of an Aboriginal person in the world [If Everyone Cared, 1977]. She spoke about her life, how she was taken as a child and forced into slavery through the Cootamundra Girls Home, which was a training centre for Aboriginal girls to become domestic help for white women. I get really angry when white women try to brush over the fact that the colonial project is not just a male one – white women used Aboriginal girls to run their homes and do the hard labour. I have to remind white women not to be complacent and remember that they’re complicit in what happened here.

‘Becky’ is a euphemistic term for a white woman, a very straight, cis-gendered white woman who is self-indulgent, white-privileged – where privilege is invisible to them, where feminism is about them and nobody but them. ‘Becky’ can be very dangerous to us, for example when you see celebrities appropriating elements of black culture.

The #MeToo movement was started by a black woman, but she was left off the cover of TIME magazine that recognised the movement as the Person of the Year… and Taylor Swift was in the middle. It is important to keep calling out ‘Becky feminism’, and acknowledge sovereign warrior women. That’s what I’m interested in.

JPWhen you talk about Aboriginal matriarchy – which you often do – what exactly are you referring to? Is it a living concept?

PBWe are often told that, if we don’t subscribe to feminism, we are being anti-women. But gender cannot trump race. Aboriginality is who we are and, for me, it comes first. My genealogy, my family stories, the fact that I’m a Wemba Wemba woman is everything to me, is central to who I am. As matriarchal people on my Wemba Wemba side, we follow all the stories and the lines of our women – my mother, my grandmother, great grandmother, etc… This is thousands of generations.

Our stories and our sense of self, how to live as an Aboriginal woman, come from that. It teaches you about how to be in the world. It teaches you about protocol, respect, how to treat other people, to be kind and generous, to share, practice reciprocity, to be dignified, to adorn yourself beautifully, to have pride when you go out, to represent your family and culture to the outside world and to our cultural gatherings.

We’ve always adorned ourselves, and part of that matriarchy for me is celebrating our beauty. We are depicted as ugly and undesirable by white Australia, we’re never written about as beautiful. So we’ve always adorned ourselves, always been proud of who we are. That’s what it is for me. It is old, it precedes feminism.

The damages of patriarchy came together with the damages of colonialism. We have to deal with violent tendencies in our own families and communities. Our trans, queer, non-binary, gay mobs go through a lot of homophobia in our own communities – much of it directly because of the influence of Christianity. The Aboriginal culture celebrated what other people called ‘two-spiritedness’. To be queer and both genders was revered, not something to be ashamed of. I think, the more matriarchal blak, the more people of colour, the more women, queer, trans, and non-binary people in the future, the better. It will be safer for everybody.

JPWe preceded this interview by commenting on how white people live fantasies of colonial conquest through travel – it’s always about finding that pristine beach. To finish, I want to propose another concept of travel, an older one, that predominated in Europe before the colonial era, when travelling happened on land, more slowly, and was predominantly centred between Europe, Africa and Asia. It was travel understood as primarily engaging not vision, but hearing; based not on witnessing, but conversing; not conquest, but building relationships. The traveller’s role was to go to another place, and speak to the learned men, and listen. I really like that – and thank you for this opportunity to listen.

PB That was exactly what I was doing in New York over the past fortnight. We had a First Nations Dialogues with other First Nations people from the US, Canada, Hawaii and Australia. In her book Decolonising Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, Linda Tuhawi Smith talks about networking as a project. She talks about how networking for Indigenous people is a form of resistance: a way of sharing information, sharing knowledge, being in communication, supporting each other. Networking is resistance, and we’ve always done it – across mobs, languages, and [now] continuing across the world, with other First Nations people. That’s what excites me the most about Aboriginal and First Nations activism: that it’s not a new thing. We’re just generationally passing it on.

A huge thank you to Paola for the time she took to speak with us, and to Tom Ross and ACCA for the photography. You can find out more about the Unfinished Business exhibition on the ACCA website.