Google Urbanism

There seems to be a growing discomfort with the current terms of engagement we, as users, have with the technological platforms that have become enmeshed in our daily lives. While we actively seek out free services that help us effectively (and efficiently) navigate virtual and physical spaces, we are still concerned with our right to privacy and ownership over the data we submit – even as we knowingly relinquish them by accepting the terms of agreement.

In a world where physical borders delineate sovereignty, tech corporations occupy murky waters between the geophysical locations of the business and the user. As they generate often immense revenue from our collective data, governmental bodies scramble to reactively introduce legislation to control data gathering, utilisation – and profits.

It might be that the power tech corporations hold is already beyond our means of control. But what are the alternative narratives? How can we proposition ourselves to best engage with tech platforms, and utilise our collective data to create better cities and promote positive societal change?

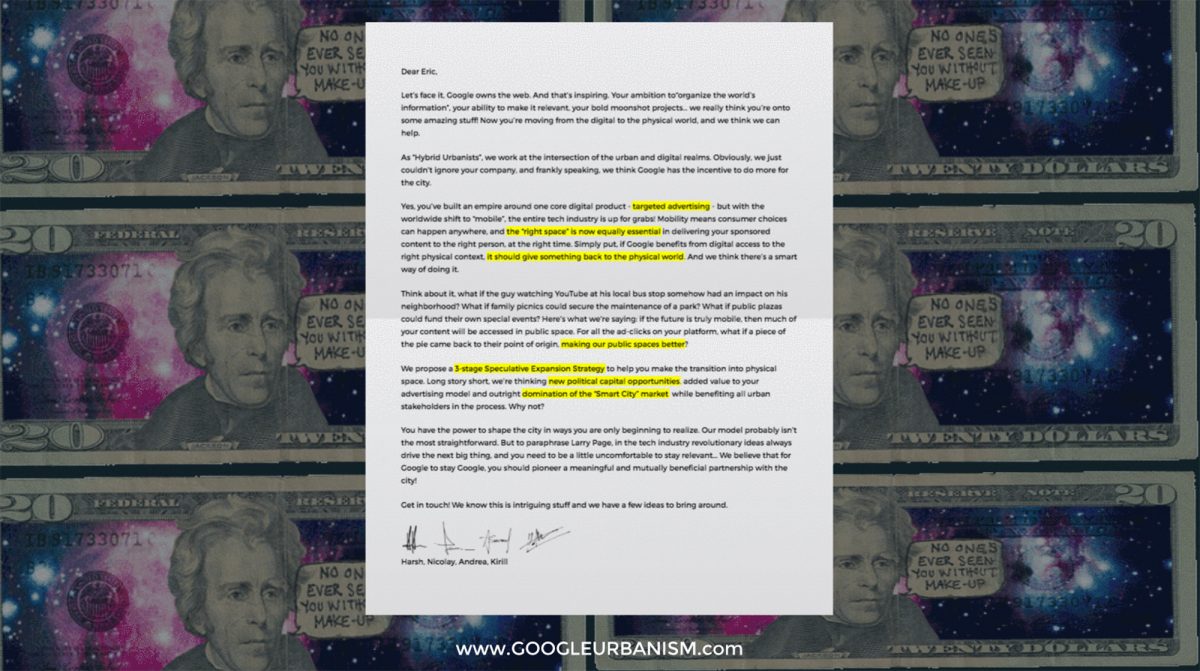

One project that looks to these questions is GoogleUrbanism, conceived at the Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow. GoogleUrbanism is an “unsolicited speculative expansion strategy for Google” developed by Nicolay Boyadjiev, Andréa Savard-Beaudoin, Harshavardhan Bhat and Kirill Rostovsky as part of the Hybrid Urbanism educational programme.

I had a chance to talk with Nicolay Boyadjiev and discuss some of the pretext, propositions and implications of their proposal.

Janie Green

What is GoogleUrbanism?

Nicolay Boyadjiev

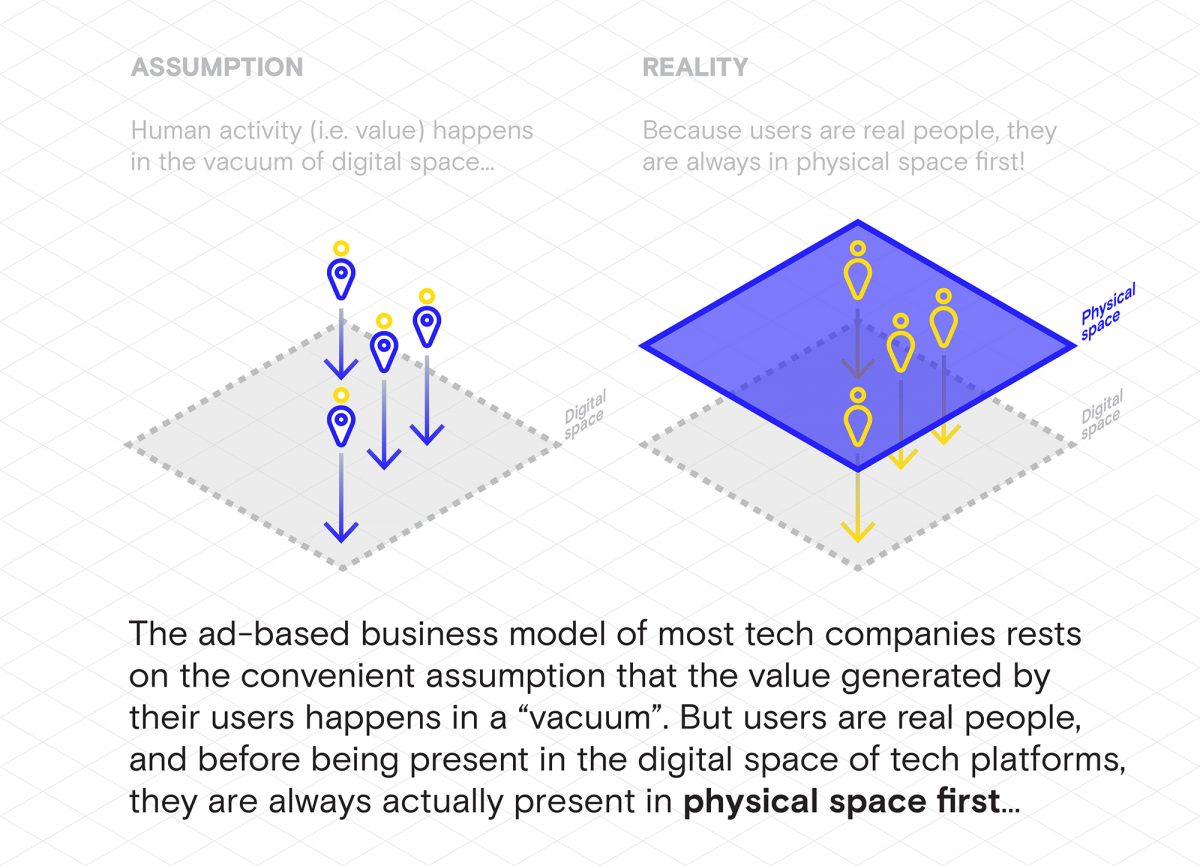

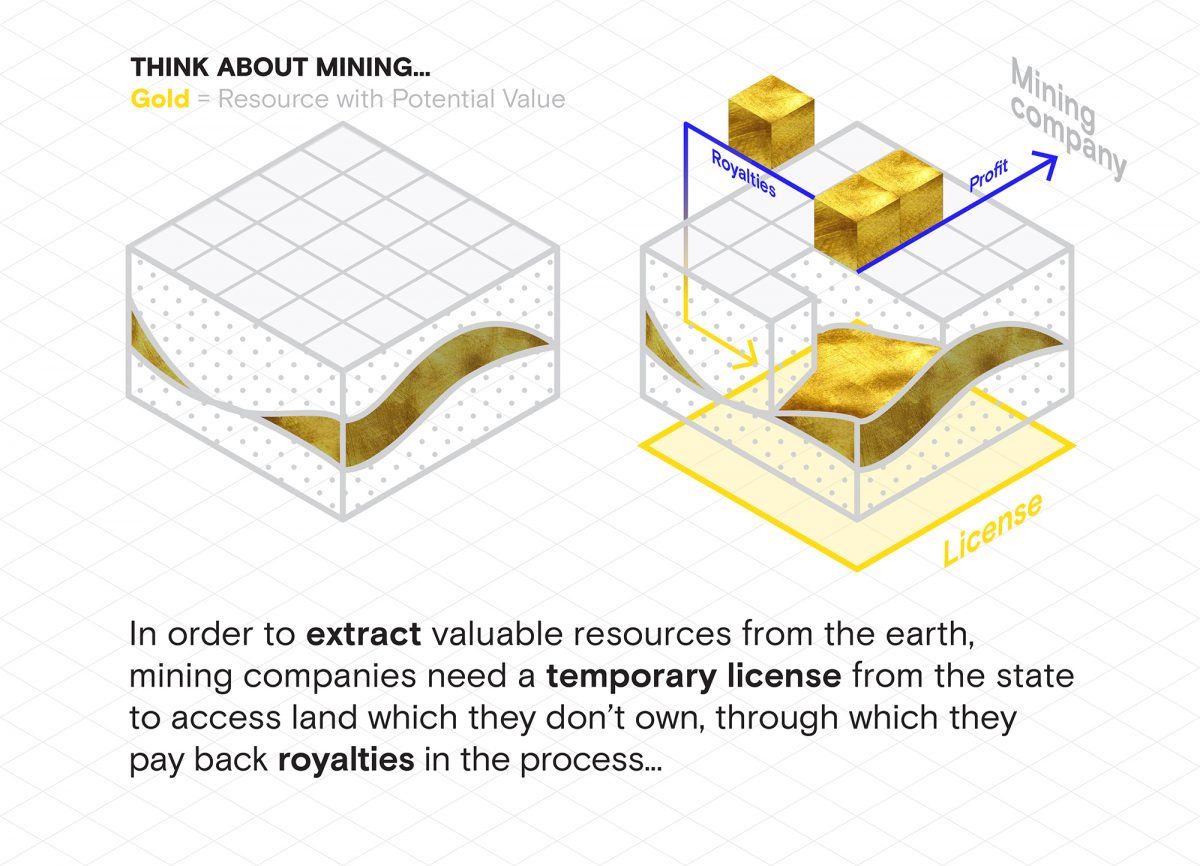

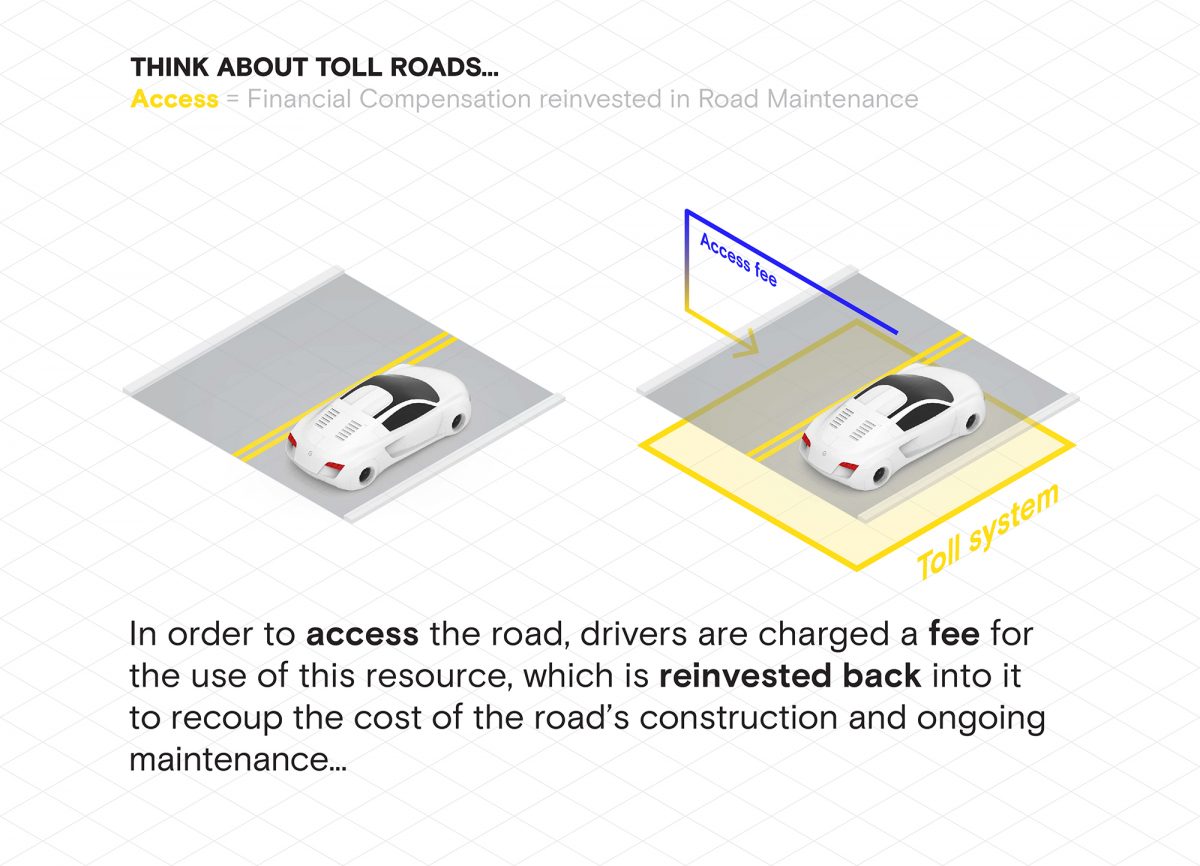

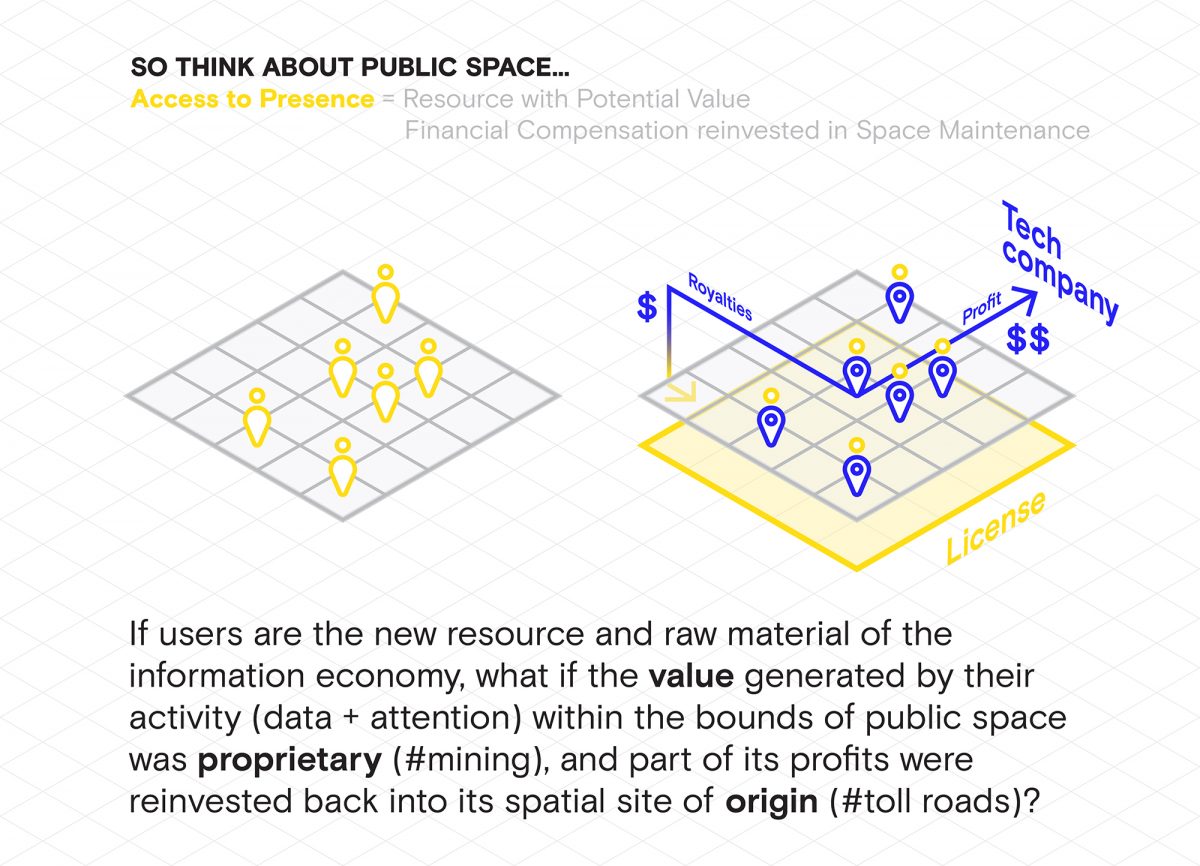

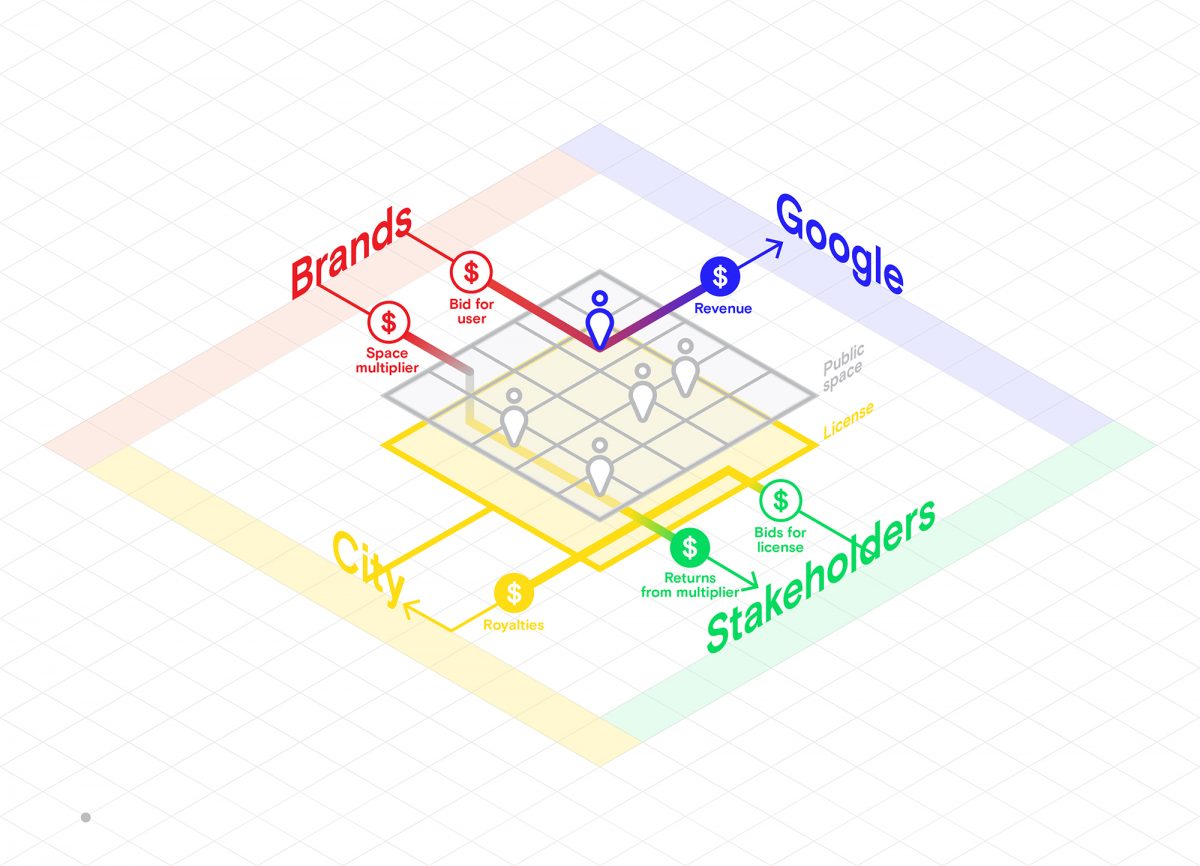

In the most general terms, GoogleUrbanism is an alternative type of ‘architectural’ project: rather than proposing a built intervention or urban masterplan, we put forward a new protocol and systemic logic for mutual cooperation between Google and the city. The project calls for a new type of licensing structure, where the profitable extraction of digital data / attention harvested from Google’s users within the bounds of public space – which we define as ‘presence’ in the project – generates financial ‘royalties’ for the city (similar to mining), which could then be reinvested in their corresponding spaces of origin to account for their maintenance and continuous improvement (similar to the toll road system). Simply put: every time Google digitally make money within the physical bounds of public space, the city takes a cut and reinvests in itself.

In order to achieve this, the project proposes an ‘unsolicited strategic partnership’ with Google and frames the proposal through their P.O.V. as a win-win scenario for both Google and the City. This was controversial by design; implying the involvement and collaboration of creeping corporate tech platforms at the heart of our sacrosanct public institutions makes most people uncomfortable… But the truth is that tech platforms are already vastly capitalizing on the digital data and attention of their users within the bounds of our real, physical world, whether we choose to accept it or not. As such, GoogleUrbanism isn’t a dystopian proposal of some alternative fictional world, as much as the difficult but necessary effort to ‘institutionalize’ this currently unchecked process of extraction, and set new terms to the currently one-sided relationship between tech platforms and the city.

JG How was the project conceived?

NB We originally developed the project at the Strelka Institute in the spring of 2016, although since then the project has been ongoing, and has proven to be unexpectedly useful to reflect on recent platform developments with regards to the city.

Conceptually, GoogleUrbanism emerged through collective conversations around two major ambitions and driving forces of the project. The first was an experiment to work with ‘surveillance’ in the urban realm as a design parameter and objective point of departure rather than as a vilified abstraction to be rejected on the basis of our own personal moral discomfort.

Second, we were interested in framing GoogleUrbanism as the opposite of a manifesto. To initiate a conversation around the topics we wanted to address, it would have been easy to draft a list of self-entitled demands of Google from the (self-appointed) P.O.V. of the city, earnestly making claims about how public space is important, what it is owed, how Google and other tech giants should pay up and so on. The project would have probably been more popular in the design community, but we were interested in moving past ‘critique’ or ‘moral crusade’ mode and challenged ourselves to conceive of the project from the strategic vantage point of Google: “under what circumstances would it be beneficial to give away a fraction of our profits to the city to improve its public spaces, and what should we get in return?”

JG I think the project fairly generously propositions itself to the benefit of Google/Alphabet, and suggests that the relationship between the City and Platform is “under Google’s terms.” Was this a tactical decision, to garner traction or collaboration with Google/Alphabet?

NB Yes this was a tactical decision, but not only in relation to Google/Alphabet. Part of our narrative was to establish that over the last 10 or 20 years, tech platforms have flourished to the extent that they have partly because they have created and conquered vast new territories with no or minimal oversight from official governing structures. Because they emerged and operated within the space of ‘a-legality’ (predating the laws which in effect would have slowed or regulated their ascent) they temporarily benefited from an unprecedented rise of power and capital, as well as, in most cases, from the benefit of the doubt.

In 2017, for many reasons, these days are over. GoogleUrbanism operates on the assumption that sooner or later, outdated taxation laws and citizen indifference / complacency are bound to shift, and it’s in Google’s best interest to anticipate and guide this shift by ‘disrupting itself’ on its own terms in a direction that’s consistent with its current strategic urban focus (as well as with its new corporate slogan of “doing the right thing”) by benefiting the city more directly.

JG How was GoogleUrbanism received by Google/Alphabet?

NB To my knowledge, the project is still under the radar – I suspect it’s less a matter of Alphabet being ‘reluctant’ to respond than being preoccupied with other pressing concerns (like starting to actually build cities…). But this may change, as we are working to re-launch an updated version of the project ahead of Google’s 20th anniversary in September 2018.

JG Proposing this kind of collaboration between governments and tech corporations potentially encourages an increase in governmental surveillance. Is it a necessary and inevitable collaboration to speculate on?

NB Yes this collaboration is potentially damaging, but not necessarily more so than a lack of collaboration. Let’s not kid ourselves about the scope of what we currently call ‘surveillance’: the systematic regime of tracking, monitoring and capturing data is not an unfortunate excess output that we can weed out if we try hard enough, but rather an essential structural component of the current economic order, as described by Shoshanna Zuboff. If you think about all the different scales of urban data capture, from the budding earth observation industry, to the pervasive mapping and other types of datasets soon-to-be collected at street level by driverless cars, to the smartphone miniature billboards / tracking devices we carry in our pockets as we walk around the city, public space is absolutely ‘prime real-estate’ for the expansion of this surveillance regime. This is happening under the nose of architects and designers who are too ‘appalled’ or ethically paralyzed to actually apply their skillset and tackle the issue as a design brief from the mixed perspective of various stakeholders.

So to answer the question: yes I believe this is a necessary, inevitable, timely and absolutely crucial project for designers to undertake.

JG The ‘Smart City’ narrative, especially in Australia, continues to revolve around the digitization of physical infrastructure. Is there a need to focus our attention towards investigating the ways in which people behave in the city, and social and cultural exchanges? And the implications of data on those behaviours?

NB I think that the global ‘Smart City’ narrative is often greatly oversimplified, which accounts perhaps for the predictable ways in which designers think about and formulate its perceived virtues. While the “digitization of physical infrastructure” seems like a genuinely new phenomenon, I think that much of the spirit and motivation guiding this process is actually inherited from the lingering tenacity of old modernist ideas: ‘efficiency’, resilience and the desire to provide a ‘better’ urban experience. There’s nothing wrong with that, but it’s a limited perspective. In the Smart City, intangible assets such as contextual interactions and relationships between people, things, events and space are much more important than sensors and smart trash bins. This is part of why we chose to focus primarily on people and behavior, and why we expanded our focus from data to include the loose concept of ‘attention’. This is also why we picked Google as a preferred partner in our project, rather than traditional Smart City players such as Cisco, IBM or Siemens.

The value of ‘context’ as an intangible asset and main protagonist in the city is at the core of GoogleUrbanism. For example, a controversial aspect of the project has always been how we defined people as a ‘raw material’ of space, rather than keeping in line with the much more humanist and politically correct notion of ‘human-centered design’. Rather than people gaining the profits from their data/attention, we claim it should be their respective sites of origin where value was extracted. This allows to assign ownership to a previously intangible and siteless asset: presence is contextual, and context is always partly spatial.

It also opens up the possibility to assign ownership to other types of relational transactions, beyond the human user. Take for example the emerging debate around the ownership of data produced by autonomous vehicles; is it held by the carmaker, the supplier of the sensors, the temporary passengers, the car itself? Why not the site-specific street on which it was harvested, as a flag-bearer of the commons? The conceptual formulation of the ‘space’ as the wallet holder of its own value was an important concept we wanted to introduce.

JG Is there plans to continue this line of research and enact models that generate real time data and revenue for a specific location?

NB This is the next logical step, and we are definitely open for collaboration in this area.

JG GoogleUrbanism was launched in mid-2016 and you have since presented the project at numerous institutions, conferences and events. What have been the most interesting responses so far?

NB The most interesting and surprising result has been the range of different reactions to the proposal. Early in the process, we made the tactical decision to prioritize simplicity and clarity of the message rather than trying to critically knit a tight-proof argument no one could refute. GoogleUrbanism was about communicating a radical story in simple terms.

As such, it’s interesting that most of the time, general audiences quickly grasp the main idea, and even when they disagree with the proposed solution, there is a kind of a commonsense acknowledgment of the main premise: “Before we’re inside the ‘digital world’ making tons of money for tech platforms, we are always somewhere in the real world first because we’re physical beings, therefore perhaps the physical space which hosts us should get something back…” By design, that’s not a very scientific claim, but we were going for an intuitive and emotional response.

Therefore, I was genuinely surprise with the variety of people from different professional communities who understand the project right away and start brainstorming and improving on the idea despite having no prior interest in these issues. I was even happy to see NYC’s parks commissioner Mitchell J. Silver tweet about the proposal, even if I don’t exactly know where and how he came across the project.

It was also interesting how our mild ‘trolling’ of conventional design wisdom sometimes had an inverse, negative reaction. Acclaimed digital technology researcher Evgeny Morozov fell for our purposefully clickbait title and used the project as a springboard to write a long article in The Guardian about how “GoogleUrbanism is a nice way of camouflage the truth” about the takeover of our cities by corporate tech interests. To be honest, I’m equally happy with this reaction, as it’s triggering the right conversation, which is also a testament to the success of the project. When you’re not entirely sure whether something is a great idea or the worst possible thing that could ever happen, I think you’re asking the right questions.

Nicolay Boyadjiev is an architect and design strategist based in Montreal and Moscow. He is currently the Design & Education tutor of the forthcoming 2017/18 The New Normal interdisciplinary design programme run at the Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow.

Strelka Institute is a non-profit promoting positive change and new ideas / values through its various education and public-facing activities. The aim of the institute is to push the boundaries of traditional design education, with an expanded definition of the “city” at the center of its research focus.