ZK/U: Workable Utopias

In 2006, independent artists Matthias Einhoff, Philip Horst, Markus Lohmann, Harry Sachs and Daniel Seiple opened a tongue-in-cheek sculpture museum on the vast overgrown field (5 hectares!) in the very centre of Berlin. The perplexingly large patch of urban wilderness, situated a mere stone’s throw from Alexanderplatz and completely out of place among government buildings and ordinary residential streets, was a former ‘no-man’s-land’ surrounding the now-demolished Berlin Wall.

Seventeen years after the city reunited, Skulpturenpark Berlin_Zentrum proposed an alternative type of historical monument: a living sculpture, public art as a process of revealing and critiquing the social, historical and cultural layers of the site. Between 2006 and 2009, more than thirty artists exhibited on the site, with installations, architectural works, video art, performances, until in 2008 it featured as one of the five main venues for the 5th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art. Artworks exhumed and examined the social forces that turned this vast landscape from central city to urban wasteland, and then subjected it to intense real estate speculation after unification. For Matthias [Matze], Philip and Harry, this long and layered engagement with a single site provided the space to imagine a different kind of public art practice – a socially conscious art embedded in a neighbourhood. On its wings, the three formed a not-for-profit artist collective, KUNSTrePUBLIK.

“The project came from the fact that we were sharing studios right next to this urban wasteland,” says Matthias Einhoff. “From our studios, we could see over the entire lot.” The initially ‘egoistic’ idea of claiming the space with other artists once they had to move out of their studios, gave way to a nuanced curatorial approach. “We realised that, since it was too much space for us, we would have to develop a curatorial concept beyond our own work. That was our starting point. And then, working with artists in Skulpturenpark expanded our international network. We found it very fruitful and enriching to work with other people. We thought it would be interesting to continue.”

But, says Einhoff, “we also realised that artists have quite a limited view on urban design – often fed by conspiracy theories and simplifications.” Wanting to delve deeper into questions of urban space resulted in two desires: to create long-term, spatially situated projects, and to include researchers into their work. Out of these twin desires, ZK/U was born.

In 2012, KUNSTrePUBLIK managed to sign a 40-year lease on a former railway depot in Moabit, in the northern suburbs of Berlin. In this partially derelict building, far from the established centres of power in Berlin’s art world, Zentrum fur Kunst und Urbanistik was born: Centre for Art and Urbanism, or ZK/U for short. Created to be part residence program for artists, part research hub, part community space for the local neighbourhood, and part agitator for change within the city, ZK/U has continued the detailed, grounded examination of urban context through art.

Right from the start, ZK/U resisted the conventions of both the art world and academic research, speaking of merging the two in a ‘third space’. “The art discourse is global, quite uniform regardless of whether the artist is from Australia, Europe, or Africa,” says Einhoff. “Their discourse is shared, but the art is very different, and the artists themselves are living completely different lives, very detached from the theory they use.” In this situation, he points out, it becomes difficult to attach art to a real physical space – meaning not just a space for free thinking, but a space where an artistic intervention can collide with local reality, “and productively evolve into something new, more down-to-earth,” says Einhoff.

“Such spaces are rare in urban life – commercial spaces can’t do it, and even community spaces are often more socially oriented than accepting of ideas. This is what we have in mind for ZK/U: going deeper into political and social discourses, not only theoretically, but in a physical and practical way, bringing ideas into the local reality. This is our main research question: how can we bring global discourse right down to the level of the neighbourhood?”

Over the last five years, ZK/U residents (around 50 each year) have developed a variety of answers to this question (under the guidance of KUNSTrePUBLIK, who have continued to create their own projects). There was Hacking Urban Furniture, for example, which looked not only at Berlin’s actual benches, bus stop shelters, and info points, but at the economic model of their procurement. “The city has a deal with WallDecaux, a company which provides urban furniture in exchange for advertising rights on them. The city gets public space furnished free of charge, but it is still very undemocratic decision-making. The citizens were never asked if they wanted their public space used for advertising, in exchange for a bench which they may not need.” ZK/U invited artists to think about this, work on alternative designs, and commissioned research essays. Not stopping at critique, they are now developing design prototypes to propose new ways forward. “This is where things come together,” says Einhoff. “The local reality, because we involve the neighbours directly, and the global advertising market, because WallDecaux is one of the biggest global players in this realm.”

Another project Einhoff singles out is VVest Life, which took place at the height of the so-called refugee crisis, when refugees from Syria poured into Germany and other Western European countries in 2015. German Chancellor Angela Merkel had publicly announced that no refugee from Syria would be turned away from Germany, leading to a million of arrivals in one year alone.

KUNSTrePUBLIK were invited to The Netherlands, which at that point was refusing to take any refugees at all. They built a tent-like Parliament out of safety vests from the Greek island of Lesbos. “We imported a shipping container of safety vests from Lesbos, where many refugees had been washed up after life-threatening journeys to cross from Turkey. So, Lesbos was, of course, full of these vests. We wanted to create some kind of sculpture with them in The Netherlands.”

Since it was also the time of the European Football Championship, the tent parliament included the recordings of voices of football fans chanting welcome songs to refugees. Public life, socially and politically charged spaces, and mass passions, all collided in a striking installation that highlighted how the very essence of community and human decency was at stake. “This is a project I have a very personal attachment to,” says Einhoff. “it is about standing up for something, being accountable.”

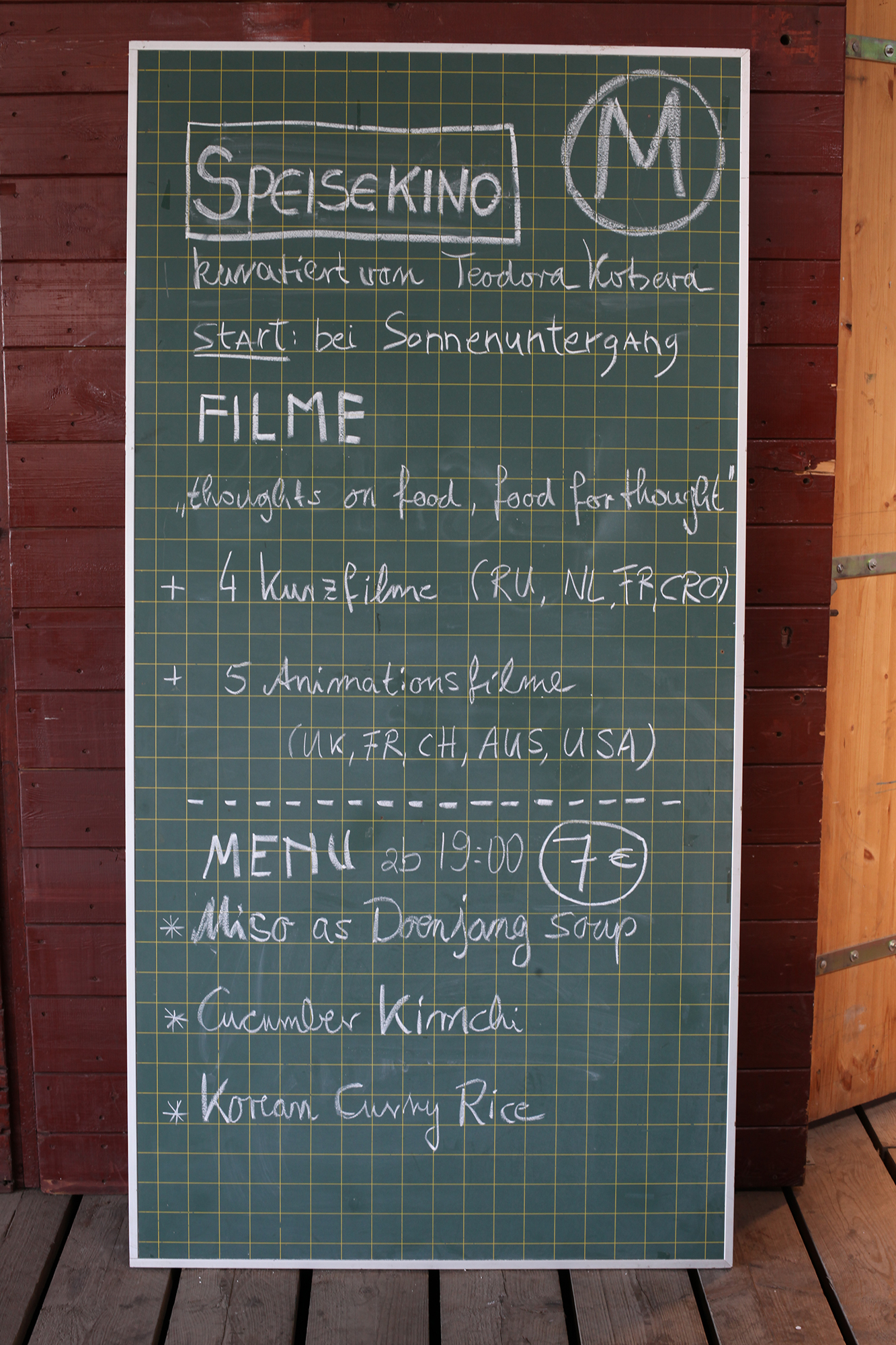

But the unlikely favourite among ZK/U initiatives is Speisekino, a dinner-and-cinema program, sometimes combined with lectures. Held in the vast and shabby Moabit railway depot, Speisekino attracts a diverse crowd of ZK/U’s international residents, Berlin artists, and local neighbours from one of the most socially underprivileged areas of Berlin. Over the years, Speisekino has grown from a one-off project funded by the local Quartiersmanagement (support funding for community-oriented activities in low-socioeconomic neighbourhoods) to become the mainstay of ZK/U’s program, now attracting around a hundred people a night. “Speisekino is very easy for people to understand and participate in,” says Einhoff. The format has become more educational over time, but still fundamentally consists of a free film projection and an affordable two-course meal.

The success of Speisekino has served as a model for developing ideas. These days, ZK/U will experiment with a project for a few years and then, if it proves a success, let it stabilise into a ‘format’ which can be exported into other contexts. Only a few weeks prior to our conversation, they launched a website, City Toolbox, documenting some of their best-working one-off projects and more durable formats, as well as those of similar groups working at the interface of creativity and local actions. “City Toolbox is an archive as much as it is a menu of formats developed to bring art and urbanism together. Some are educational formats, others are practical, but all try to translate discourse into local action. If you felt you had a methodology you wanted to share, this is a platform where you can do it.”

With five years under their belt, and another 35 to go, ZK/U is increasingly becoming more financially sustainable. There are plans for expanding the Moabit space – which started off as a draughty, empty depot, and the early years of ZK/U involved artistic curation as much as they involved plastering and DIY construction work – to add a publicly accessible terrace that can be seen from the adjacent S-Bahn trains, as a kind of urban stage. “If we can do it well, it will change our visibility in the city,” says Einhoff, noting that ZK/U’s international visibility is huge compared to their somewhat fringe position in the highly competitive Berlin art scene – exacerbated by their Moabit location.

Politics is another stage they seek to access. “We are invited to conferences and symposia a lot, to give a different perspective – but in the end decision-makers just do what they always do. Because our work is a mixture of art and urbanism, people don’t take us seriously. It’s become important for us to create impact – not just in changing conditions in the city, but impact in terms of political influence.”

Two years ago, ZK/U started an initiative to revitalise Haus der Statistik, a former East German public building on Alexanderplatz, unused since 2008: “The federal government was planning to let the building rot and then just sell the land.” The initiative started with in cooperation with another three-four citizen groups, then turned into a huge movement, eventually pressuring the municipal government to buy the 55,000 sqm building and commit 75 million Euros to its restoration. The revitalisation proposal includes social housing and co-housing, as well as public and creative uses, and new ground-floor passages to increase the permeability of the block. ZK/U might be one of the new residents, though there are no plans to abandon Moabit prematurely. “I think this illustrates that we can have an impact – we can pressure administration and politicians towards a more socially-oriented city development. This project is a good blueprint – if we succeed. But I am optimistic.”

Moving into Haus der Statistik would bring Matze, Philip and Harry back to the same neighbourhood where they started Skultpurenpark in 2006 – then the centreless centre of a capital in political and planning limbo, now the focal point of a gentrifying metropolis. Einhoff tells me that the former urban wilderness has now been fully developed, mostly by private developers. It took Berlin 30 years to clarify land ownership since reunification, since much of the property owned by the now-defunct East German state could be claimed by the pre-WWII owners, a long and painful process exacerbated by the fact that many previous owners were Jewish families that had long left Germany. Clarifying land ownership, which is only coming to completion now, has really sped up the real estate market, says Einhoff, and is compounded by the consequences of the financial crisis of 2008, such as extremely low interest rates that have encouraged Europeans to invest their savings: “Over the last five years, this has created enormous pressure on the market, speeding up [redevelopment] in a very physical, tangible way. We have been seeing change for a decade, but it has become visible now. Berlin has changed quite a lot.”

For almost 30 years, Berlin has been a no-man’s-land of urban planning, a finance-poor but land-rich city attracting creatives and political progressives both for its abundant housing and for its radical history. Some of the most interesting experimental architecture, art and building collectives today come from Berlin, perhaps because it is easier to operate in a speculative-creative space when rental insecurity and mortgage repayments are not an issue. Einhoff agrees, citing insights from ZK/U’s residence program: “We can see the difference with the artists coming from the US, who are much more focused on producing sellable work.” Germany has been able to maintain a certain level of public funding for art, he notes, which has allowed artists to remain more socially-minded, more politically radical, but also better able to engage in the realpolitik of the city.

Seeing a thread of connection between KUNSTrePUBLIK and groups such as Raumlabor, Einhoff describes his generation as, on the whole, less interested in utopian ideas than practicable utopian realities, “which means having to compromise with what’s already here.” Many people are actively pushing for a paradigm shift in the political system, be it through creative protest, political engagement, or involvement in neighbourhood politics. “We want to dedicate our time to developing things that might change in our lifetime, rather than to utopian ideals that won’t.”

“I think people are politicised for historical reasons – seeing the transformation from a city that used to be super-accessible, to now becoming like every other city…”

What are the responsibilities that come with that?

“Everyone has a responsibility as a citizen,” Einhoff quips.

Yes, I say, but not everyone has a train depot.

“We feel it’s ethically right to fight development based purely on neo-liberalism, to fight for a more heterogeneous approach to city development with a stronger social angle. Since ZK/U has to work economically, we’re aware of the importance of finance, but it isn’t necessary to treat the city and buildings solely as an asset – an asset for investors who don’t even live there. We have a responsibility as citizens, and more power to voice that responsibility because we have a building, and a public profile.

“And yes, it’s a real privilege to have this building,” Einhoff adds seriously, “it’s not, like – a normal thing! We’re fully aware of this, and therefore we have to give something back.”

Is there a danger that we will look back on this time in Berlin and see artists as causing the gentrification of Berlin? On this, Einhoff stands firm: “Every art institution and every artist add to the quality of cultural life, and this can easily be instrumentalised for the value of real estate. This is, without a doubt, a fact. But, as much as the artists talk about how we are the ones causing gentrification… no, it’s the real estate business. Making your neighbourhood more liveable with art is nothing bad. It’s the lack of political and legal instruments to stop the rents from rising.”

It’s so simple, he says: if there is rent control, it doesn’t matter what and how much the artists do. If the city were a little wiser, a little more realistic about developing affordable housing to take the pressure off the market, we would not be at the mercy of neo-liberalism. He would like artists to stop feeling guilty: “Create pressure on politics, create pressure on your legal decision-makers, and then you can make as much art as you want.”

Thank you, Matze, for taking the time to chat. All photos are courtesy of KNUSTrePUBLIK, except where otherwise noted. ZK/U is celebrating its fifth birthday with a party on 16 December: check their website for more details.