A human being is the whole world, according to Mierle Laderman Ukeles

You may not know it, but maintenance art keeps you alive, everyday. From your mother’s unpaid labour of love to the workers who wheel away your weekly rubbish or sew your clothes in far-off factories, you are plugged into a system of human endeavour that enables you – on a bodily, municipal and ecological level.

In some cities, say Copenhagen as compared to Caracas, that cycle runs smoother than others. But the fact is that every discarded wrapper or glass bottle must end up somewhere. And whether it’s landfill or a treatment plant, your rubbish is guided there by human hands that you have probably never thought to stop and shake. That is, until Mierle Laderman Ukeles came along – the artist who made a movement out of maintenance.

In 1979–80, Ukeles shook the hands of 8,500 sanitation workers or ‘san-men’ across the five boroughs of New York for her landmark ‘Touch Sanitation’ performance, thanking them face-to-face with an old-fashioned pump of the hand for “keeping New York City alive”. Over eleven months, Ukeles spent several mornings, afternoons and nights each week doing systematic ‘sweeps’ of the city’s 59 municipal departments to make her incredible two-part work (including the aforementioned Handshake Ritual and Follow in Your Footsteps, which saw Ukeles shadow and learn the movements of the san-men). She fronted up to 6am rollcalls and went out on collection rounds, observing the san-men’s resilience on the mean streets of late ’70s New York in the midst of a crippling fiscal crisis. The sanitation system maps and maintains the city and Ukeles mapped it – no mean feat for an independent artist in the pre-GPS, pre-internet age. Ukeles has said: “I liked the idea that sanitation goes everywhere, and they never, ever stop. That’s a great model for art. Art should go everywhere all the time. There’s no special place, no special time.” For Ukeles, Touch Sanitation was a portrait of New York as a living thing – a city kept alive by and for its people. Ukeles thinks of sanitation as “supranational” and “omnipresent”, fundamental to human survival across borders and cultures. The work of sanitation and maintenance is where a society both begins and ends.

It took a female artist to honour these (mostly all) men who were unseen by society while doing its essential work – nonetheless derided as ‘woman’s work’. “They felt they were considered part of the waste itself,” says Ukeles over the phone when I call her in New York from ‘the future’, 14-hours ahead in Melbourne. Touch Sanitation was Ukeles’s first work as the official unsalaried artist-in-residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation (DSNY), a self-initiated role that has defined her place within that city and society at large, for over 40 years. Ukeles calls her workplace “the major leagues of the maintenance world”, a huge conceptual and real-world platform from which to actualise projects that deal with the intersection between humanity, the city and ecology.

Crucially, Ukeles made a connection between the work and social status of the san-men and her own experience as a mother. Post-partum, she found herself “invisible” to curators and art-world people who saw children as signifiers of retirement from art practice (a judgment reserved for mothers, not fathers, and sadly still widespread). “At that point there was such little language and visibility [for motherhood and domestic labour]… it just made me furious. Actually, the anger became a touchstone for me. I would see other workers who felt like, Why don’t they see my personhood? They were very angry and I knew that; I ‘got it’. It wasn’t an intellectual understanding. I felt it in my soul,” Ukeles recalls when I ask about that formative time.

When we speak, Ukeles is back at DSNY’s offices in Lower Manhattan (she has moved from the city in recent years to be closer to her children and grandkids, but retains her office with sanitation, which she frequents regularly), sorting her heaving archive of papers and ephemera. She is figuring out what to donate – to the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art, her gallery Ronald Feldman or to friends – or turf: “What’s paper and what’s art? In my case, sometimes paper is art. It gets a little complicated!” Indeed, Ukeles’s groundbreaking Manifesto for Maintenance Art 1969!, then as now a rallying cry for artists, feminists and workers, was typed in a fit of fury onto paper in one sitting. At home with a young baby, Ukeles found herself “divided in two”: the Artist and the Mother. It dawned on her that her avant-garde heroes Jackson Pollock, Marcel Duchamp and Mark Rothko had never suffered a similar identity crisis or changed a nappy in their lives of “pure creativity”. In an interview with Tom Finkelpearl, she describes artists like Pollock as not “living in a planet that has finite resources, where we need to stay alive, in connection with other people… It had an evil underside of autonomy, only the ‘I’; not acknowledging who holds you up, and who supports you, and who’s providing the food, and the raw materials, and who are the people who are taking them out of the earth, and what are their working conditions, and what are the pollution costs of moving materials all around the world, who’s paying for what, and any fact of human life.”

I ask Ukeles about the connection between her situation and that of the city, which was immortalised in Manifesto. “From the very beginning, it wasn’t me bitching about society telling me what to do but about the inter-relationship between personal maintenance, about maintaining society which was actually focused on the city within the urban context, and about maintaining the planet.” In fact, Manifesto’s key terms of ‘maintenance’ and ‘development’ are inspired by those used in the New York Comprehensive Plan (Ukeles’s husband Jack was then a city planner for New York). To Ukeles, ‘development’ stands for progress, newness and pure creation in the Pollock vein, while ‘maintenance’ is care, sustenance and survival. The former cannot exist without the latter: creation is often easy; it’s the maintenance and follow-through that is hard. Ukeles reimagines the social order by uniting her lived experience as a feminist, artist and mother with that of the ‘majority’ of humanity – the maintenance worker across genders and nationalities. “The underlying image in my work is always a sort of big-system image, and I don’t know if it’s generally understood. I get marginalised as a happy houseworker… but my interest, along with the worker, is the city. How does the city work? And sanitation is such a great way to learn about the city because they are experts in this incredible scale of coordination,” she said to Finkelpearl. One can see a shared spirit with Jane Jacobs, another woman who saw the entirety of New York as her public, shaping history for collective good, against the odds.

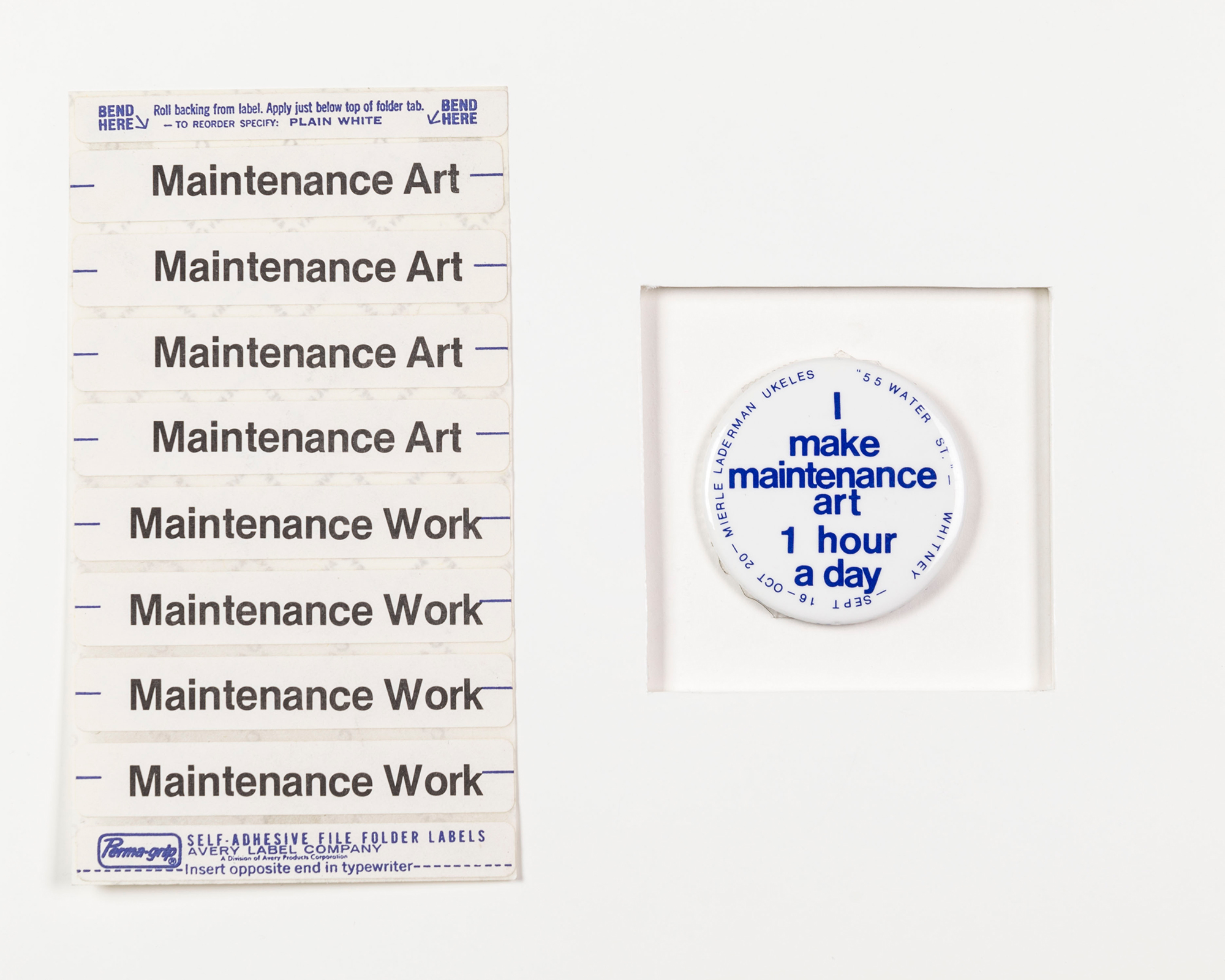

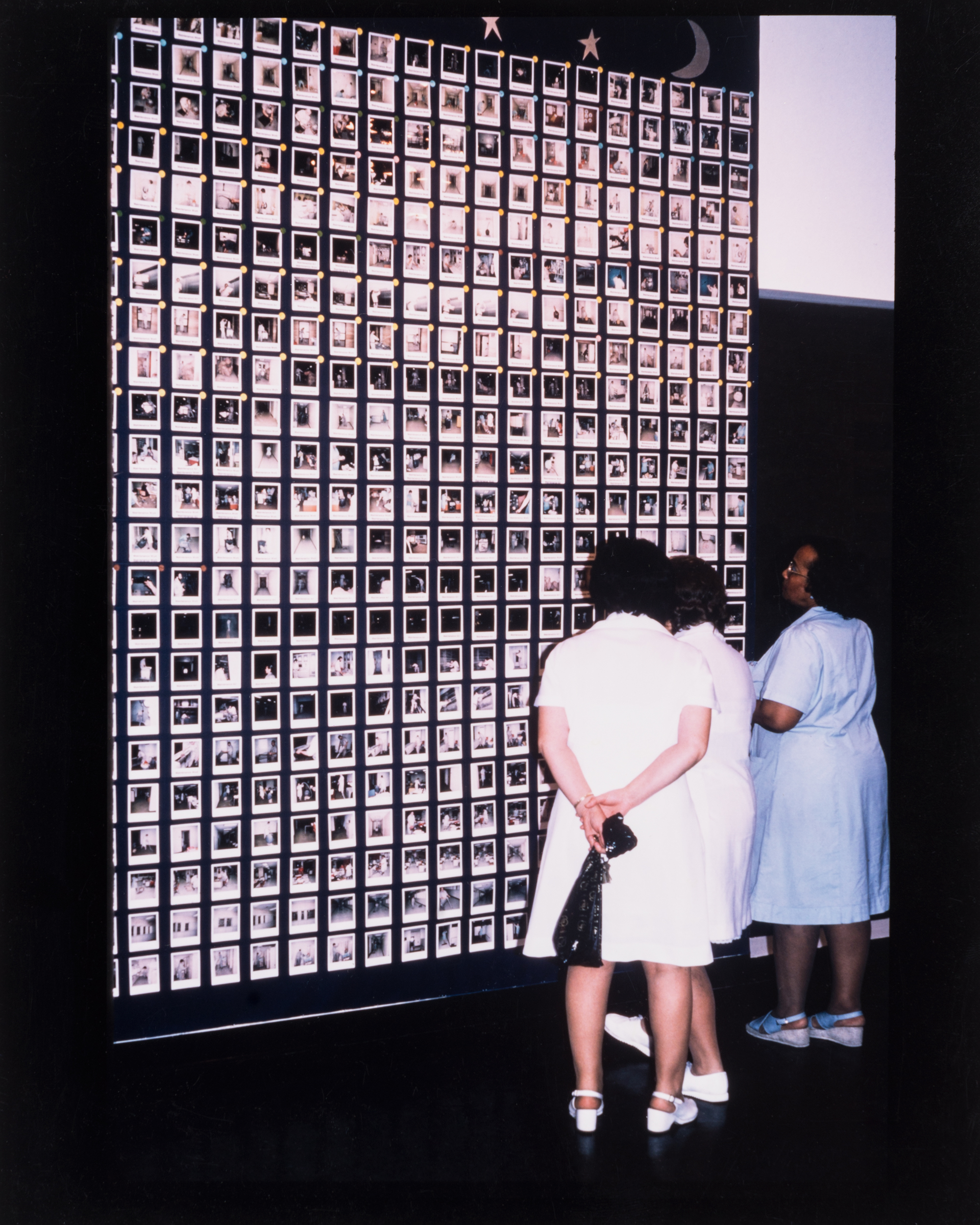

I Make Maintenance Art for One Hour Every Day (1976) was an important prototype for Ukeles’s collaborations with DSNY. For ART < > WORLD, an exhibition in the Whitney Museum’s downtown branch, exploring the connection between living systems and art, Ukeles spent the course of the five-week exhibition inhabiting the whole building: observing, talking with and photographing its 300 maintenance workers. Ukeles says she was obsessed with the building, a fancy Richard Meier–designed skyscraper in Lower Manhattan. She recalls its “Apollonian order”: management forced maintenance workers to wear buttoned-up shirts and bow ties while they dusted, mopped and cleaned so they might “disappear” into the moneyed context. Ukeles worked around the clock to capture over 700 polaroids of the workers. She asked them to name the moment when they were photographed as either ‘maintenance art’ or ‘maintenance work’. As the weeks went on, Ukeles’s grid of photographs began to accumulate in a collaborative portrait of the building’s otherwise unseen workforce. The workers – people who had not previously felt welcome at the gallery – began frequenting the space to see themselves and their co-workers on view. Ukeles says this blind faith and transference is critical: “When you’re an artist, you kind of don’t know what you’re doing, but you have this force in you that’s pushing you and you go with it. I realised later that what I’m doing is transferring the power of decision-making from me, who’s making the artwork, to the worker. That’s the basis of all of my works.”

Ukeles’s belief that maintenance art is universal has seen her make several large-scale collaborative ‘work ballets’ with workers, communities, trucks, barges, hundreds of tonnes of recyclables, glass and steel across the world, from the US to Europe and Japan. Although Ukeles has had major museum shows of late (a retrospective at the Queens Museum in 2016–17 and an international touring exhibition initiated by Grazer Kunstverein, Austria, 2013–14), her work almost always takes place in public, co-created (before co-creation was a ‘thing’, Ukeles points out) with its worker constituents, never with a predetermined score or script. Each work ballet is based on months of research, discussion and choreography, drawn from the skills and desires of the workers themselves (Ukeles: “What have you always wanted to do?” Tug-boat captain: “Make a figure eight across the river!” Ukeles: “‘OK!”). For the Echigo‑Tsumari Art Triennial in 2003 and 2012, Ukeles and the local snow-removal division conveyed the romance of Romeo and Juliet to an adoring local and international audience. These intricate and poetic works imbue hard machines – snow ploughs and garbage trucks – with real human emotion, inspired by the revolutionary spirit of the Ballet Mécanique and the Constructivist legacy of the worker as culture-maker.

Ukeles’s current project is Landing, a permanent public artwork sited at Staten Island’s Freshkills Park, a former landfill (“the size of three Central Parks”) that is undergoing a slow transformation into a public park. Landfills have long fascinated Ukeles as the ultimate ‘social sculpture’. She loves the earthworks of Robert Smithson, Michael Heizer and Nancy Holt; but where these works are in remote, privately owned landscapes only accessible to the privileged few, Ukeles is interested in landfills as public land art within city limits, to expose society’s cycle of consumption to itself. While Freshkills Park will not open to the public for another 30 years – (“I’m 77 now, so you do the math!”) – Ukeles is hopeful Landing will be viewable to small groups by 2019. She sees Freshkills Park as a “fraught and fragile ecosystem [symbolic of] what it means to dwell within this messy vitality, remarkable diversity and extraordinary complexity of the world”. This is the uneasy but fertile ground where Mierle Laderman Ukeles lives, works and thrives: a space of interdependency between nature and culture, worker and society, the artificial and the real.

This article originally appeared in Issue 8 of Assemble Papers, ‘Metropolis.’. A very warm thanks to Mierle Laderman Ukeles for being so generous with her time for this interview. We look forward to finding out more about your new Staten Island work (and hopefully dropping by New York to see it!) in the coming future.