Remembering Enmore’s urban landscape in Mirror Sydney

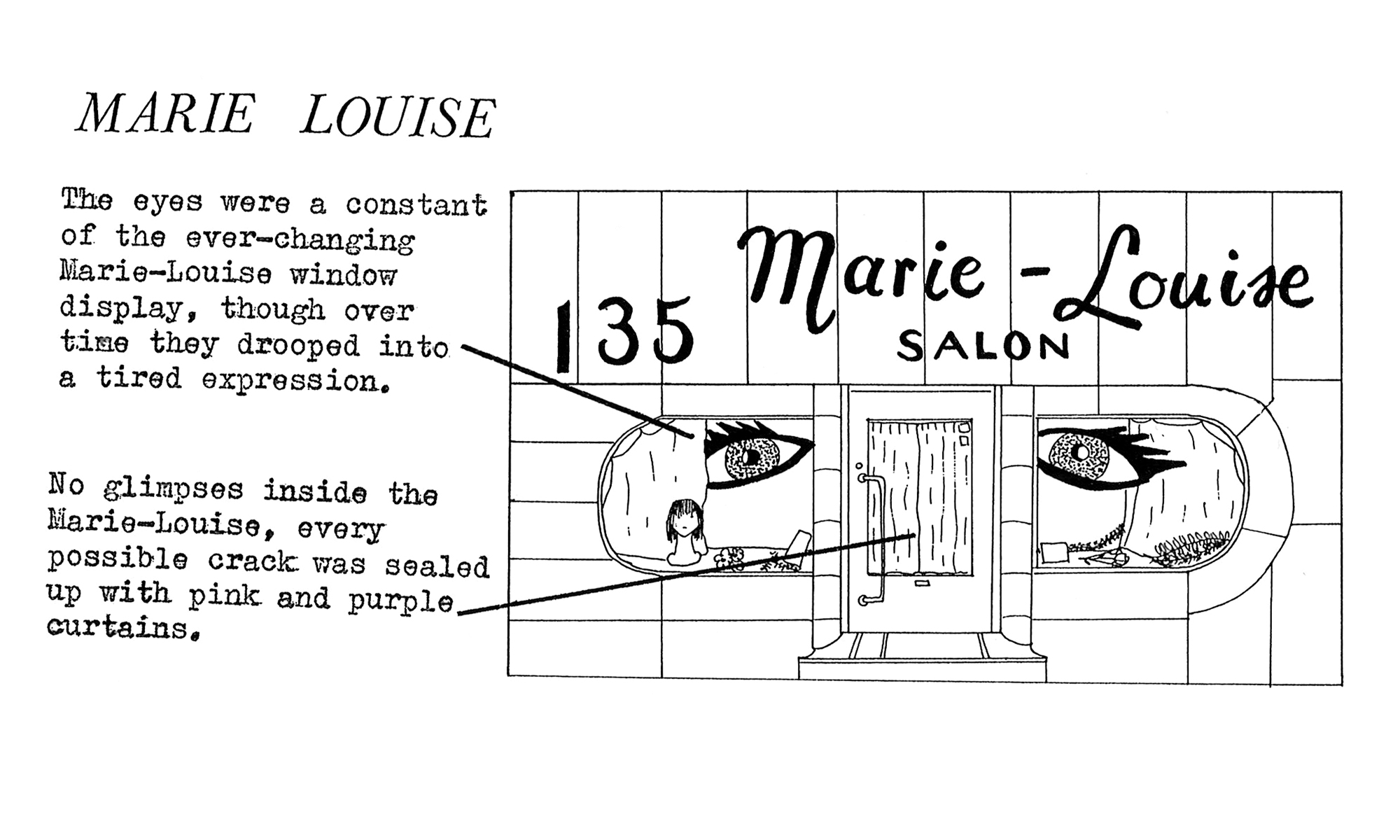

The pink-and-mauve facade of Marie-Louise Salon is a surprising sight among the shops on the main street of Enmore. Its curved windows are like two jewelled eyes; indeed, for a long time a large cardboard eye with spiky black eyelashes hung in each window. Then the eyes were gone and the windows redecorated with a collection of soft toys, pink and purple artificial flowers and Christmas baubles. Among the flowers was a framed photograph of a man in a police uniform, standing guard over the display.

Marie-Louise ceased to operate as a hairdressing salon many years before this window display of toys and flowers, but it didn’t have the derelict feeling of an empty shop. The display changed now and again and the mail was regularly cleared out from under the door. It attracted a lot of attention, people stopping to photograph its pink exterior and to peek through the windows, although their curiosity was thwarted by the curtains which prevented any glimpse of the interior.

The Marie-Louise Salon was run by two siblings, Nola and George Mezher. Both were hairdressers and became public figures when they won the first-division prize in Lotto in 1982. Their winning Lotto numbers, they explained, were derived from saints’ birthdays. Most Lotto winners choose anonymity, but the Mezhers were happy to appear in the media as they used their prize money to set up a charity. They established the Our Lady of Snows soup kitchen on the corner of Pitt Street and Eddy Avenue, in one of the archways of the viaduct below Central Station. The unusual name, Our Lady of Snows, harks back to a church in Rome, itself named for a divine miracle of the fourth century when snow fell in the middle of summer.

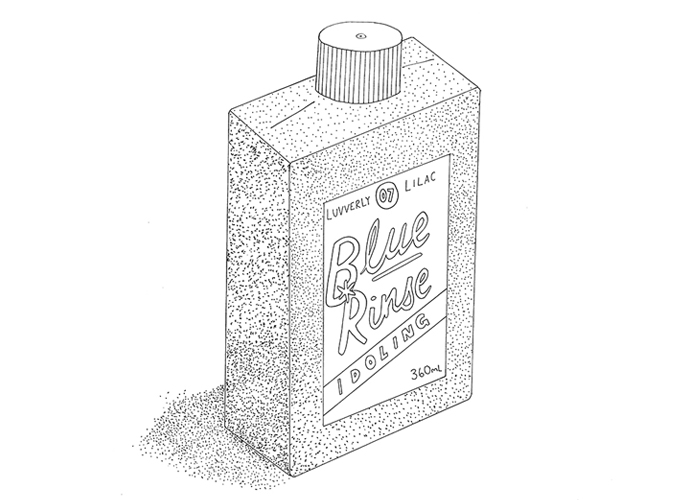

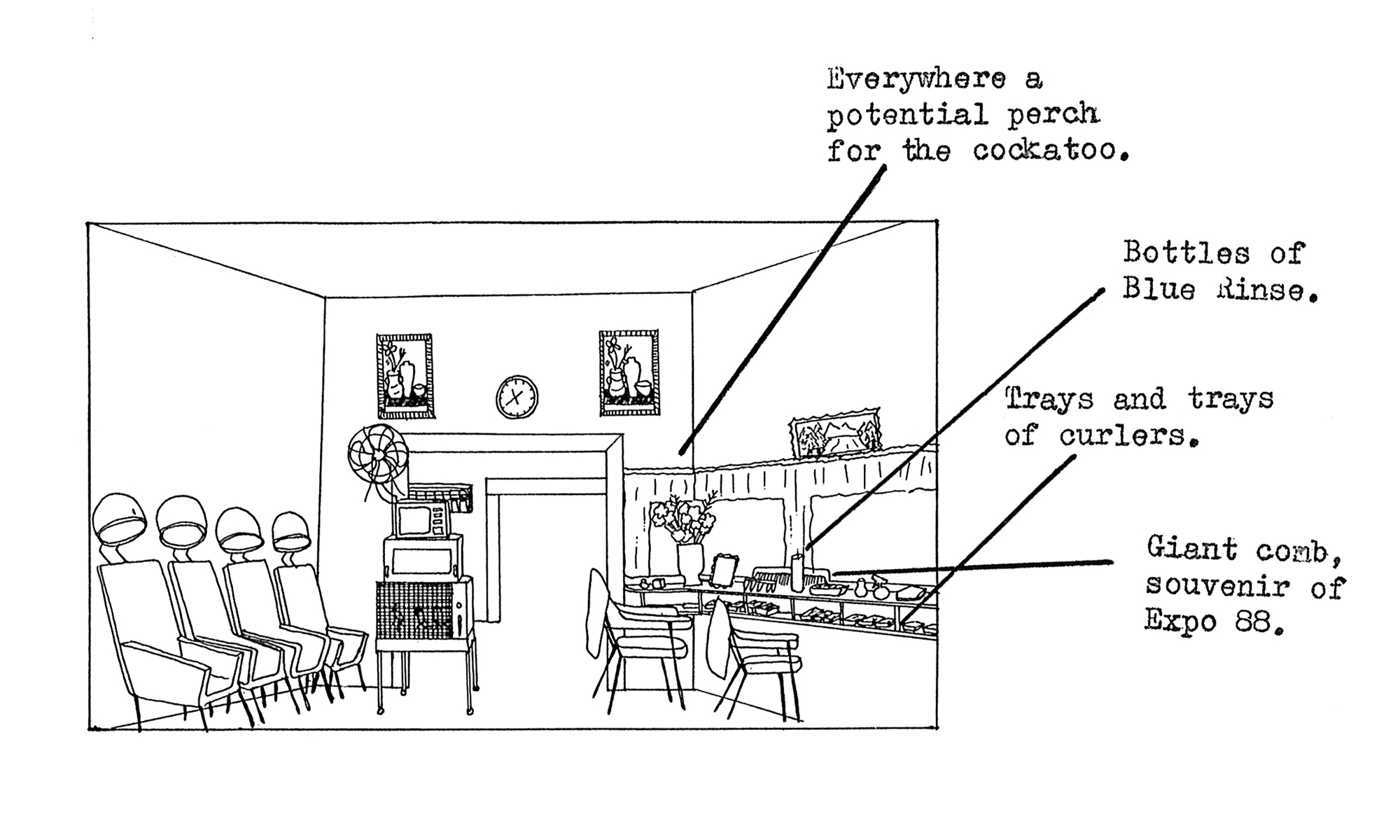

I would sometimes see Nola in the Our Lady of Snows van, holding up traffic while reverse parking on Enmore Road. If the salon door was open I’d go into Marie-Louise for a trim. I’d sit in a vinyl chair with a towel pinned around my neck, eyes wandering over the photographs and decorations surrounding the mirrors. Photos of Nola and George, pictures cut out from magazines, artificial flowers, jumbo-size novelty combs. Trays of curlers and bottles of blue rinse, swatches of different hair tints: there was always more to observe from my position in front of the mirror. Behind me was a row of hair dryers on pedestals, their domed heads like giant snowdrops. As Nola worked on my hair a cockatoo hopped over the backs of the chairs, chattering. When it got too close to where she was working Nola would command, ‘Go to bed,’ and the bird would hop back on its perch and tuck its head under its wing.

After Nola died in 2009 the Marie-Louise, with its commemorative display of pink and mauve objects, became one of Sydney’s memorial stores. Memorial stores are shops no longer open for business that act as unofficial museums, in memory of people and times that have gone. George continued to maintain and modify the window display, visiting Enmore Road often to check on the salon and visit the St Luke’s op shop next door. St Luke’s also has a window display of cheerfully miscellaneous objects in haphazard arrangement: a bottle of Avon aftershave shaped like an alarm clock beside a Venus de Milo candle and an embroidery kit and a souvenir plate from Crete – a shifting spectacle of goods in limbo.

Enmore has been slower to gentrify than neighbouring Newtown. The rows of shops along Enmore Road are a timeline of sorts, moving unevenly between past and present. A stern statue of Queen Victoria, sceptre in hand, presides over the road from above the Queens Hotel. Elements of the 1980s and 1990s alternative culture that centred around Newtown and Enmore remain on Enmore Road, the Gallery Serpentine goth boutique selling corsets and gowns, the Polymorph body piercing studio, the Alfalfa House food co-op with its share-house notices in the window. The road itself holds a deeper history, as an Aboriginal walking track, leading through the Gadigal and Wangal country that is the inner west West of Sydney.

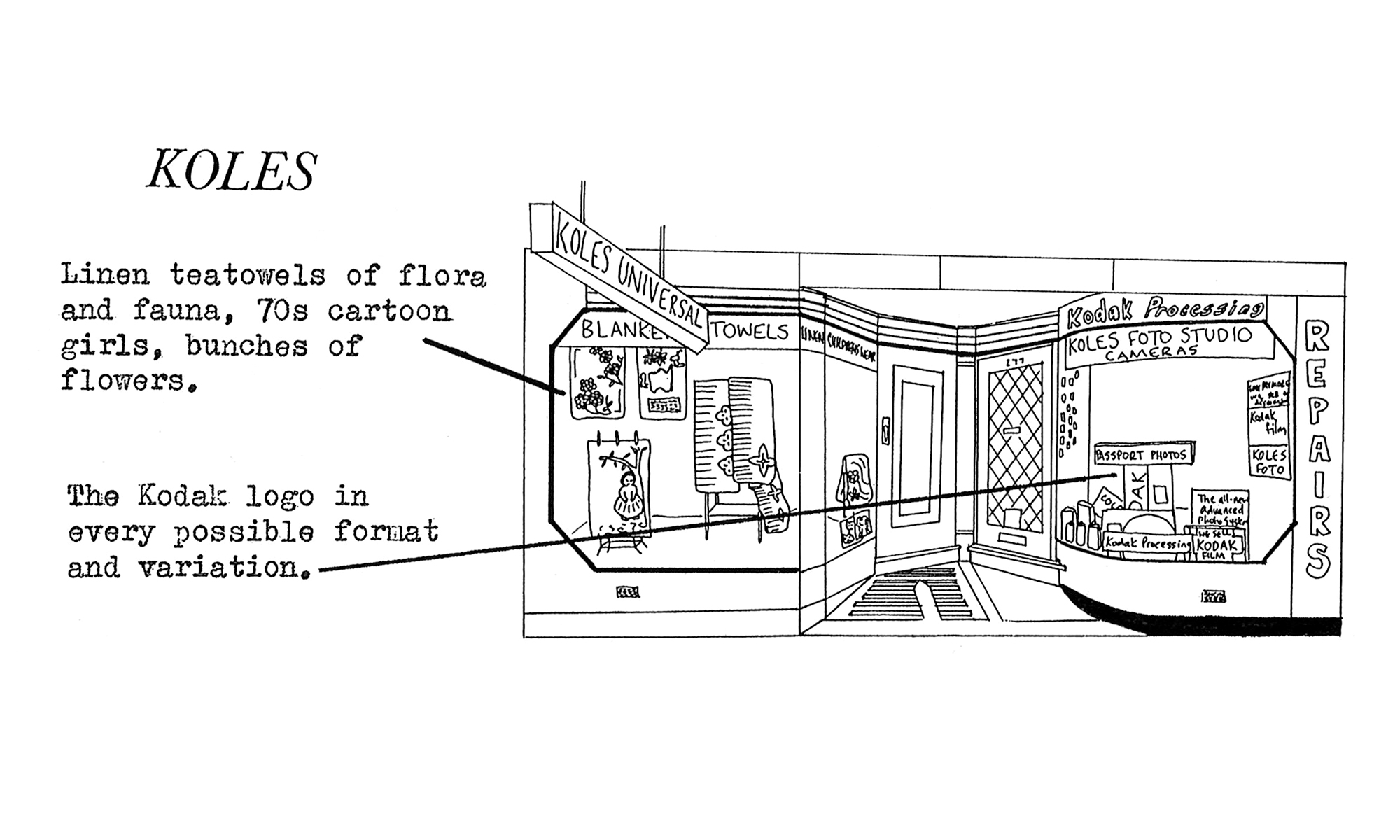

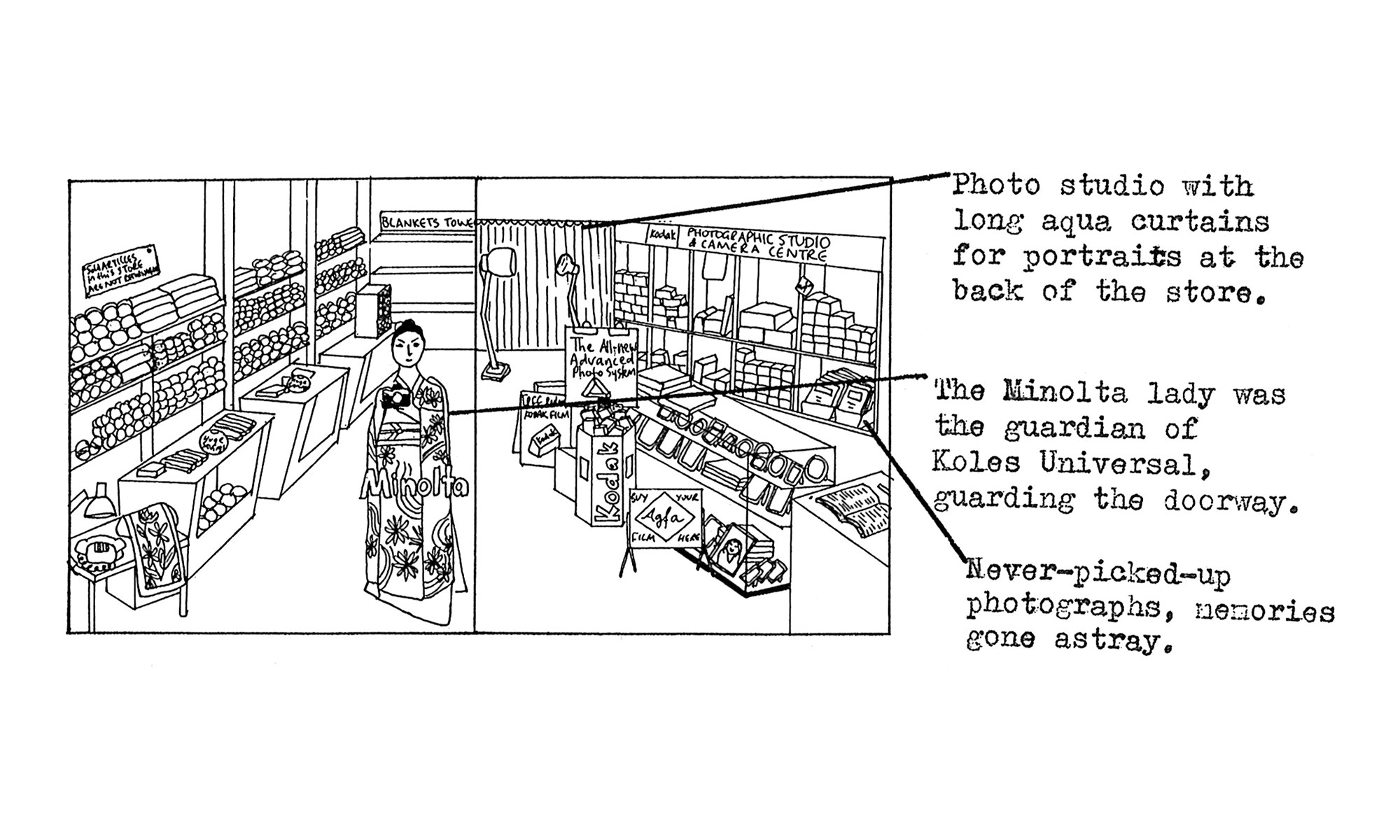

At the same time that the Marie-Louise window display memorialised Nola, another memorial store existed on Liverpool Road in Ashfield. Like Marie-Louise it had two big, curved windows, this time painted yellow and red: Kodak colours. On one side was Koles Foto with a display of photographic paraphernalia, on the other Koles Universal, with an arrangement of 1970s linen tea towels in the window. The stores were run by a couple, Mrs Koles with the manchester store, Mr Koles the photographic store.

The photo store opened irregularly. Once when I saw Mr Koles was inside I went in nervously to say hello. It wasn’t that the thought of meeting him made me nervous; it was more that the store seemed an apparition. I looked in through the windows so often that it was strange to go inside, as if I was walking into a photograph. Inside, a tall, elderly man with black hair and big yellow-tinted glasses greeted me from behind the counter. I bought some film, explaining that I still liked to use it, and this was enough to start us talking. He told me he had wanted to be a photographer since he was ten years old. His first camera was made out of wood, he explained, stretching his hands out to indicate the size and shape of this invisible antique.

I stood at the counter as he told me stories from his life. Many of them were about his wife, and as he spoke of her he looked towards the window of her store with its colourful tea towels. They had been married for fifty-nine years, he said and then told me, exactly to the day, how long it had been since she died. They were both Russians from Harbin, in cold, remote northeast China, and had emigrated to Australia after the Second World War. To make their surname easier for Australians to pronounce they had shortened it from four syllables to one. On the shops’ signs the name Koles is equally as prominent as another fabricated name, Kodak, which was chosen by company founder George Eastman because he liked the assertive sound of the letter K.

I listened to stories from Mr Koles’ life, about love and grief, risk and change. He spoke with zest, as if by telling them he was able to bring the times and the people back: playing in an orchestra by the river one Shanghai summer, the intense cold of Harbin in winter, coming to Australia with his wife. After her death Mr Koles continued to arrange the window display in her store with floral towels and patterned dishcloths neatly pegged to stands. Inside her store the shelves were stacked with balls of wool, and from behind the door a cardboard cut-out of a geisha holding a Minolta camera smiled out into the street.

I’d hoped to visit Mr Koles again, but his store was closed every subsequent time I passed by. I would always stop to peer in through the glass at the cabinets of photographic equipment decorated by Kodak promotional signs from different eras. The shop counter was a still life, a mid-action scene of an open phone book, the page-to-a-day calendar open on 17 January, a Yashica-branded ashtray filled with odds and ends. Behind it the wall was hung with packets of Polaroid film and Instamatic disposable cameras, and on a shelf were drawers with packets of photographs indexed by surname, still waiting for people to come and collect them. The very back of the store was a studio set up for portraits, with a long green curtain and spotlights. All this rested in a static arrangement, and I could stand at the window and skim my eyes over it, noticing something different each time. It was a museum to memory with its stacks of expired films and outmoded cameras.

To look away from the Koles window was to re-enter the present-day world. The Ashfield streets, busy as usual, with people queuing outside the New Shanghai restaurant, the most popular of the Liverpool Road Shanghai stretch that also includes Shanghai Night, Shanghai Food House and Taste of Shanghai. As with the twin Koles shops, many of Ashfield’s stores come in multiples. Janny’s Cakes and Maria’s Cakes side by side, both selling birthday cakes and red bean buns. The two independent fruit and vegetable stores both advertised their excellence: a choice between the paradise of Fruitopia, and Ashfield Fruit Market, where people shopped underneath a banner in cut-out wooden letters: You’ve tried the rest / Now here is the best. Both went on to be demolished to make way for new developments. All along Liverpool Street, such pairings continue.

To visit the Sydney epicentre of anachronistic shops, I need only return to Parramatta Road. The Olympia Milk Bar, unchanged since the 1950s, is Sydney’s best-known example, enduring for so long that it has come into notoriety. Now the dimly lit, cavernous milk bar has a Facebook fan club with thousands of members. Reports of fans’ visits accumulate on the page, with descriptions of the milkshakes and cheese and tomato sandwiches consumed and accounts of conversations with the sometimes reticent owner, an elderly man whose background is the subject of much speculation. These reports often come to the same point of agreement: that the Olympia’s consistent presence is a welcome counterbalance to the surge of change everywhere else.

There are a number of time-capsule stores along Parramatta Road. There is the never open but fully stocked Ligne Noire perfumerie, like a corner-store version of the Mary-Celeste, the ship discovered in the Atlantic Ocean abandoned with everything onboard intact. Nearby, Nelly’s International Hair Salon is clad in particoloured brown tiles and has a red-and-silver sign with a silhouette of a woman with an afro and hoop earrings. Nelly cuts your hair while her Pomeranian runs in circles at your feet and the TV chatters in the corner.

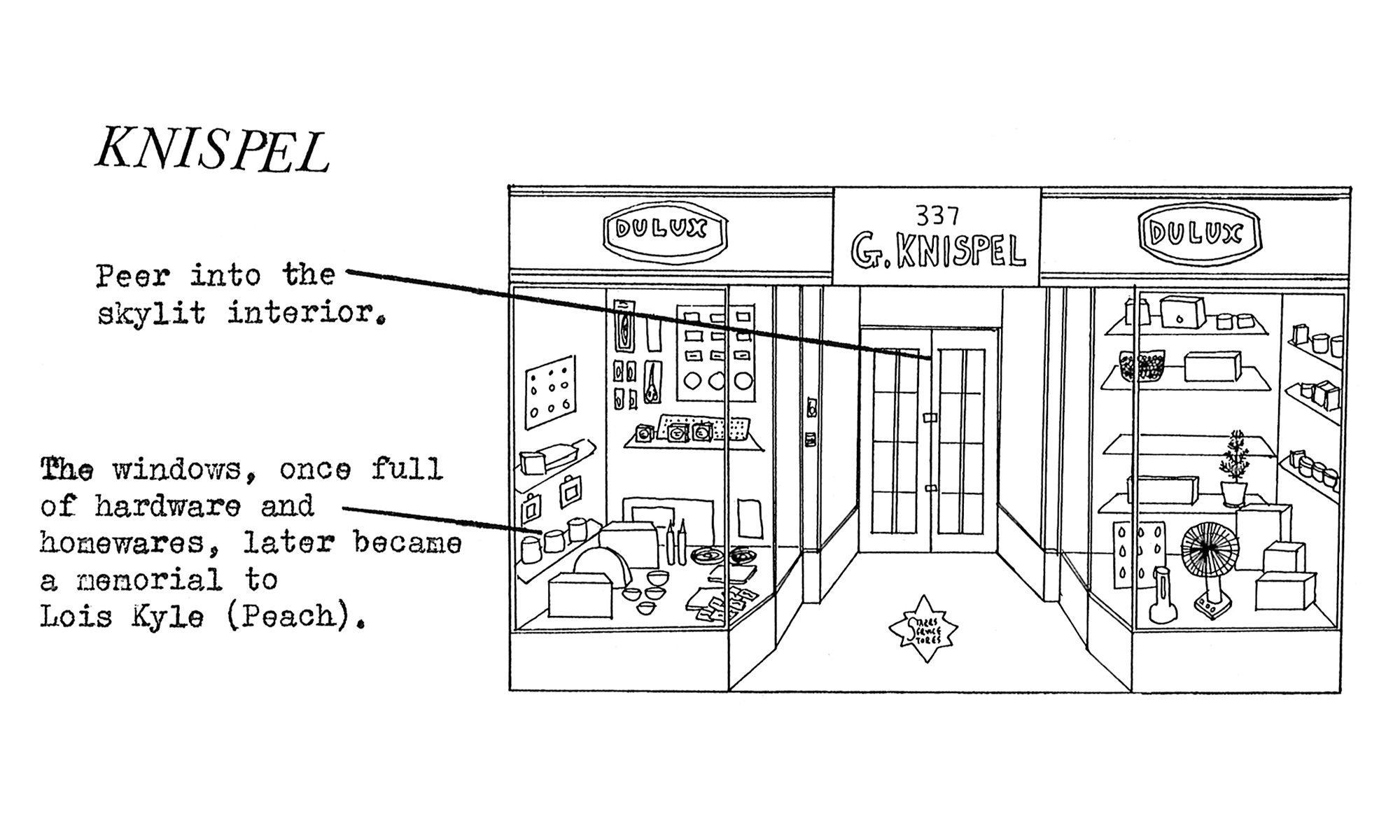

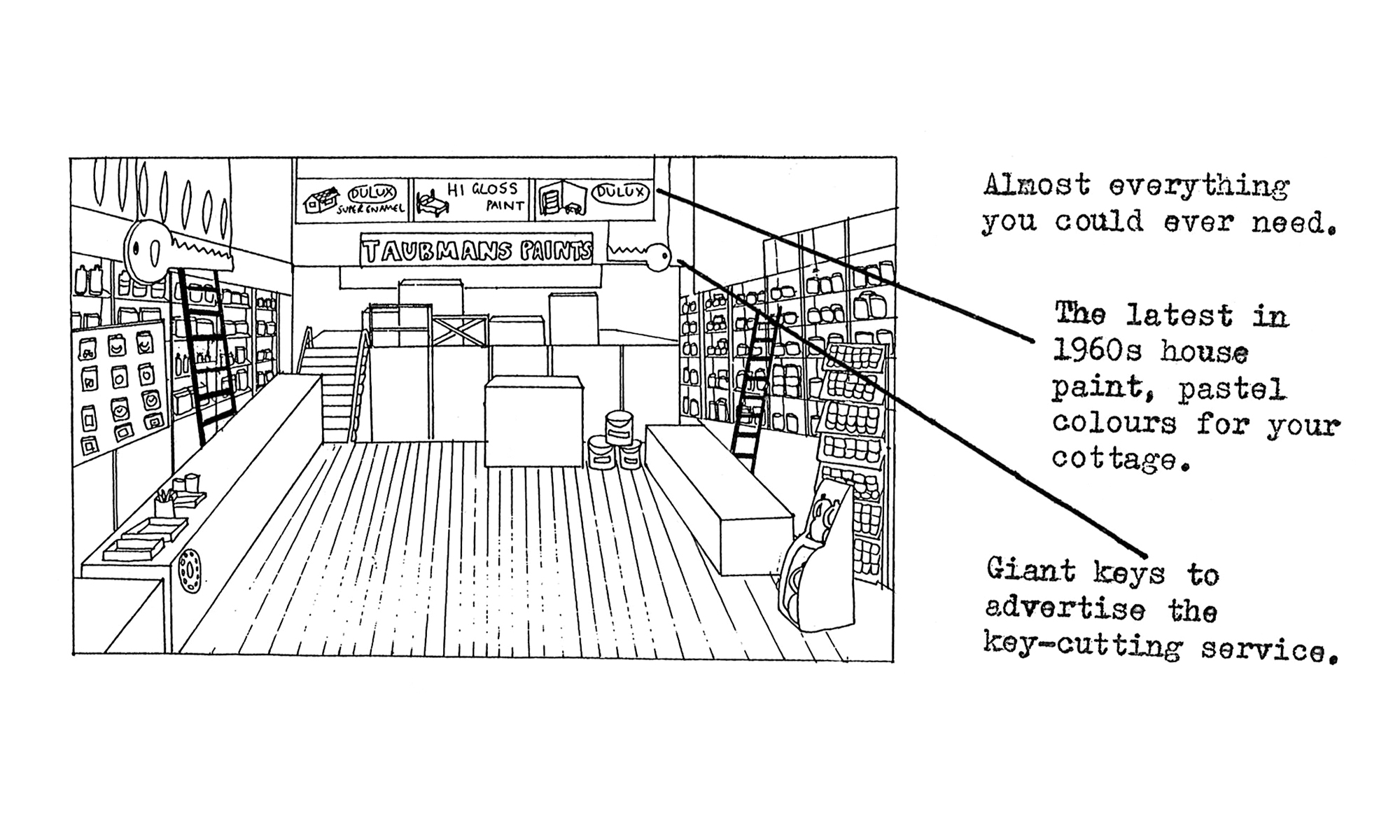

These stores exist within their own bubble of time but they aren’t memorials. Parramatta Road’s most recent memorial store was Knispel Hardware, located among a run-down row of shops in Leichhardt. Like Ligne Noire, for a long time the shop was perpetually closed with all the stock remaining inside. The products were still on the shelves and the 1950s signs advertising Taubman’s paints hung from the ceiling. The two front windows were arranged with a collection of hardware, artificial plants, tool catalogues and an oversized light bulb with the legend KEYS CUT painted on it. I’d had a key cut at Knispel years ago. With its origins in mind it became a lucky charm which I keep on my key ring, even though it is to a house I moved out of many years ago.

Then all the contents of Knispel Hardware were cleared out, the signs taken down from the ceiling and stacked against the walls, and the floorboards swept. The windows were emptied and only a few objects were left there, some artificial flowers and a red Eveready CLOSED sign leaning up against a wooden box. The windows became a memorial to Lois, the shop owner, who died in 2009. Taped to the inside of the glass were a series of photographs – Lois behind the counter, as a bride, with her family, heading out the door of the shop one day in her later years – and a piece of paper printed with the words Lois Kyle (Peach), sadly missed, and the details of her funeral service.

Most of the photographs were taken down soon after the funeral but the artificial flowers remained, and a dusty plastic Santa holding a bunch of balloons that would once have lit up when a power cord was connected. One black-and-white photograph was left, pinned to the back wall of the display window, of Lois in the store leaning against the counter. In it sun streams through the skylights and a wooden ladder is propped up against shelves that reach to the ceiling. Lois leans back on the counter with an air of self-assurance, at the centre of her domain, ready to dispense brooms and scissors and life advice to her customers.

When I was looking in through the door of Knispel the light from the skylight gave the room an eerie beauty, a sense of suspended animation. Shafts of sunlight illuminated the bare floorboards and the few items of furniture left inside. This was in contrast to the deteriorating exterior, the windows covered in graffiti scrawls and boarded up where they had been smashed, the doorway with piles of trash blown in from the street. All was coated with fine black diesel soot from the Parramatta Road traffic, a dust that quickly ages everything it covers.

These three memorial stores lasted for many years but eventually they changed. At Marie-Louise and Koles FOR SALE signs appeared, new and final window displays. Marie-Louise was the first. It was a shock to see that it was not exempt from change. There had been something eternal about Marie-Louise, as though it were a jewel fixed so tightly into Enmore Road that it would always be there. In Ashfield, a tarpaulin was hung up in the window of Koles’ photography store and, peeking in through the gaps, I saw that the cabinets were empty of their cameras and expired film. Mrs Koles’ store also had bare shelves, apart from a sign wishing Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year from a festive season long passed, and a white cash register marooned in the centre of the counter.

Then boards went up to cover the windows of Knispel, soon to be plastered in posters advertising beer and upcoming concerts. In Ashfield, Koles too was boarded up, although in a more eccentric fashion, with two domestic wooden doors with round metal doorknobs in the centre of the hoarding. Then these disappeared and new shops were revealed, two grey boxes. The SOLD signs came down from Marie-Louise and were replaced by new ones, written on pink cardboard. Marie-Louise Memorabilia Sale. Grab Your Piece of Inner West History. Sticky Beaks Welcome.

A crowd of people gathered on the pavement outside Marie-Louise on the morning of the sale. There were rockabilly girls with their hair in pin curls, curious locals who had never seen inside, and people who had once been salon regulars. One woman had lived in Enmore since the 1970s and used to come past often and say hello to Nola. The Marie-Louise always had a surprise, she said. Once there were ducklings swimming around in a bathtub in the corner. The windows of the store were constantly changing. Nola would sometimes seat hair models in there, to read magazines and pose as their hair was styled.

Eventually the pink door opened and the interior was for a moment a tableau: the curtained mirrors and trays of rollers, the pink and mauve capes and the bottles of blue rinse neatly arranged on the shelves. The pink clocks on the wall ticked through the minutes as the store was gradually dismantled, people buying things here and there, the vinyl chairs and the vases, the pink towels and bottles of Fanci-Full hair rinse. I picked out a giant novelty souvenir comb from World Expo ’88 and a bottle of blue rinse as my own Marie-Louise souvenirs, and a pink business card for ‘George and Nola Mezher, Leading Sydney Hairdressers’. A few weeks later the building was gutted, with only the pink and purple facade remaining.

These memorial stores were, ultimately, expressions of love, and the shops extensions of their owners. The Marie-Louise was Nola and George, the Koles stores were a husband and a wife, and people came to Knispel as much for Lois as for paint or keys. All of the memorial stores faded slowly, remaining as objects of contemplation long after they had stopped trading. Even when their vestiges disappear entirely, there will be stories of blue rinses and ducklings, of expired film and linen tea towels. Keys cut at Knispel will still open doors.

Many thanks to Vanessa Berry for letting us publish this wondrously evocative excerpt from her new book, Mirror Sydney. Vanessa will be launching her book in Melbourne on 28 October at Embiggen Books – see here for event details. Can’t make the launch? Order yourself a copy of Mirror Sydney, Giramondo Publishing, 1 October 2017, $39.95 here.