Nathalie de Vries of MVRDV creates new sites of collectivity within cities

In the Netherlands you often hear the phase ‘God created the earth, but the Dutch created the Netherlands’, alluding to the idea that almost every square metre of the country has been altered, designed and ‘improved’ by human hands. Nathalie de Vries, co-founder of Dutch architectural office MVRDV, believes that it is this background of living in a country of man-made environments that gives her office greater confidence in designing the future of our cities.

MVRDV has created visions of cities as hybrids – built and landscaped environments in a post-nature world. Yet, there is a deeply humanist undercurrent to their work too, a desire to create spaces for fledgling communities – sites for collectivity between apartments and between buildings.

At Expo 2000 in Hanover, MVRDV presented a multi-storied pavilion – at the time, a daring vision of the future. Exploring the theme ‘Holland creates space’, the pavilion positioned six archetypal Dutch landscapes on top of one another. Trees grew through its floors and wind turbines spun on its roof. In the 15 years following this provocation, these innovations now seem familiar, almost expected, seen in sustainable projects around the world. Nathalie explains, “You see how fast reality catches up… in 2000, there were a lot of people looking into this pavilion and [they] were amazed by it. But nowadays, we’re already thinking at much larger scales about the development of our cities and our countries.”

In their more recent explorations of the future, MVRDV have started to think beyond the building to landscapes and cities as hybrid structures. In China Hills at the Beijing Centre for the Arts, MVRDV ran projections on the Chinese metropolis of the future: density, population figures, and the required air, light, food and energy to support it. Through this investigation, MVRDV began to question whether the current building typology – towers with shiny facades – had the capacity to provide for these essentials. China Hills instead offered a biophilic vision of termite-hill-shaped buildings with stepped terraces that give space to grow food and capture energy.

As architects, MVRDV don’t just focus on data processing and image making, but also on depth and width – how to move around and live in these cities. Nathalie believes that, “to look at our cities, our countries, as constructions, I think that is one of the most important topics in our work.”

In their housing project Nieuw Leyden, MVRDV bring their interest in constructing cities to a much more tangible and immediate scale. In this project for 670 dwellings, MVRDV created an urban plan for the precinct, setting constraints for other architects to respond to. MVRDV designed the streets, parks and building envelopes to ensure pedestrian-friendly spaces and appropriately scaled houses with good access to sunlight, while ensuring the precinct was well connected to the rest of the city. Within this framework, families, developers and housing associations have a fair degree of freedom to decide what each building looks like. And, by including a mix of housing, retail and educational sites, the development starts to mimic the organic growth of a real city. Nathalie explains that the aim was to create a framework flexible enough to accommodate individual architectural visions while keeping a sense of cohesion and collective expression: “We try to set the urban rules, the rules on how to build on just half an A4 [sheet of paper]. It’s about finding out what you want to control and what you don’t want to control. Is it important that every room has the proper amount of daylight? Is it important that they’re all white or black or brown? Pick your battles, I would say. Start with the quality. And then the rest will follow.”

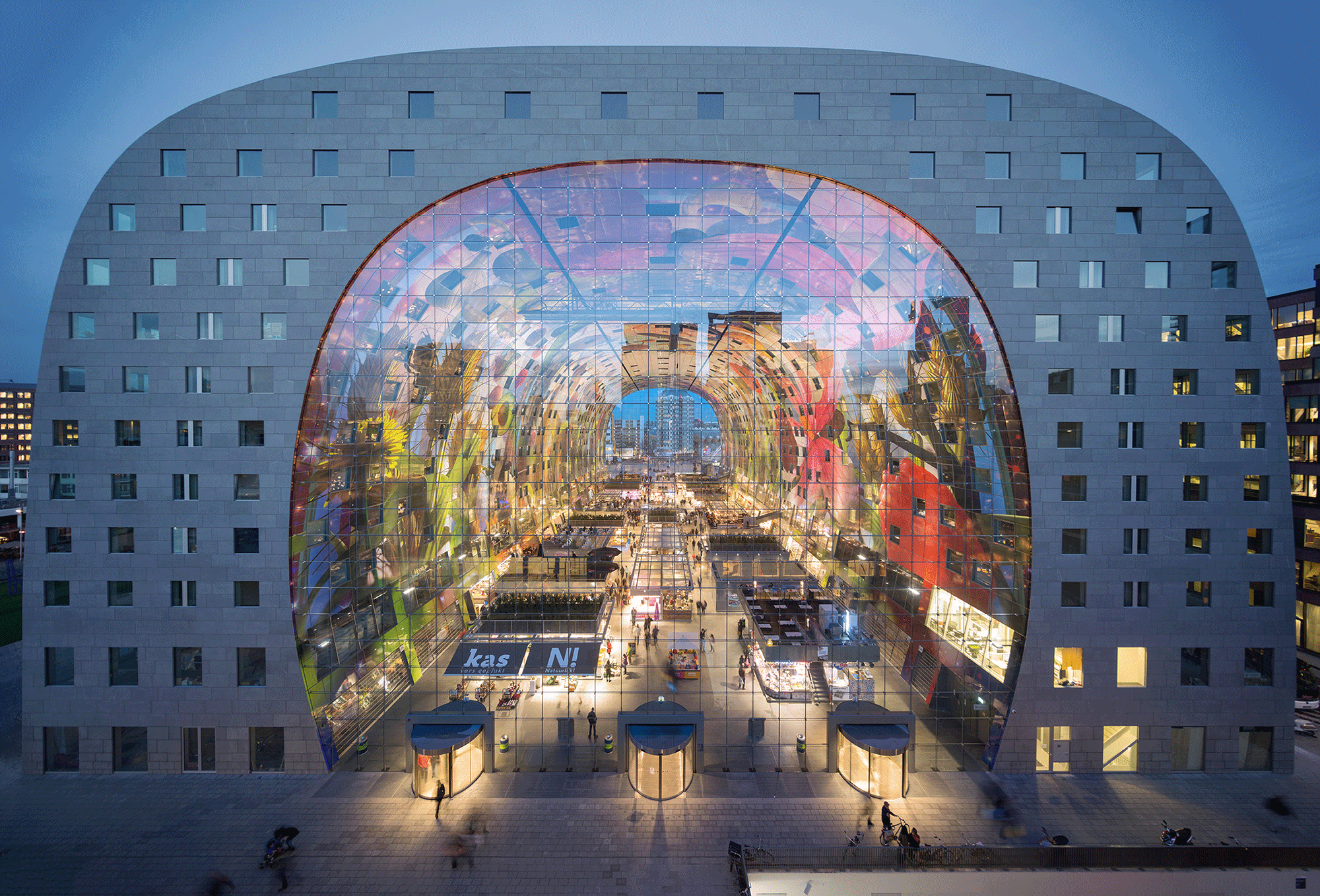

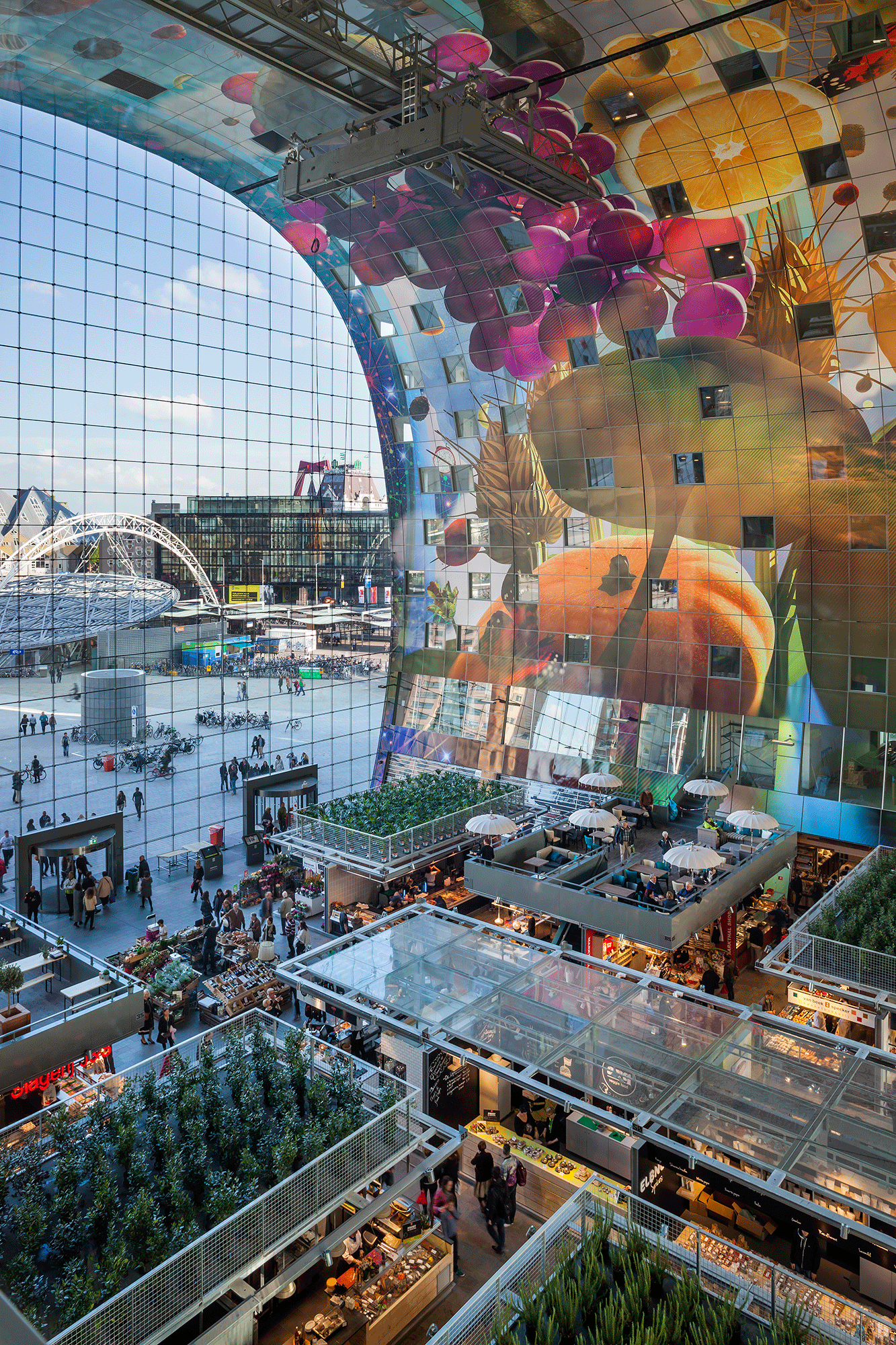

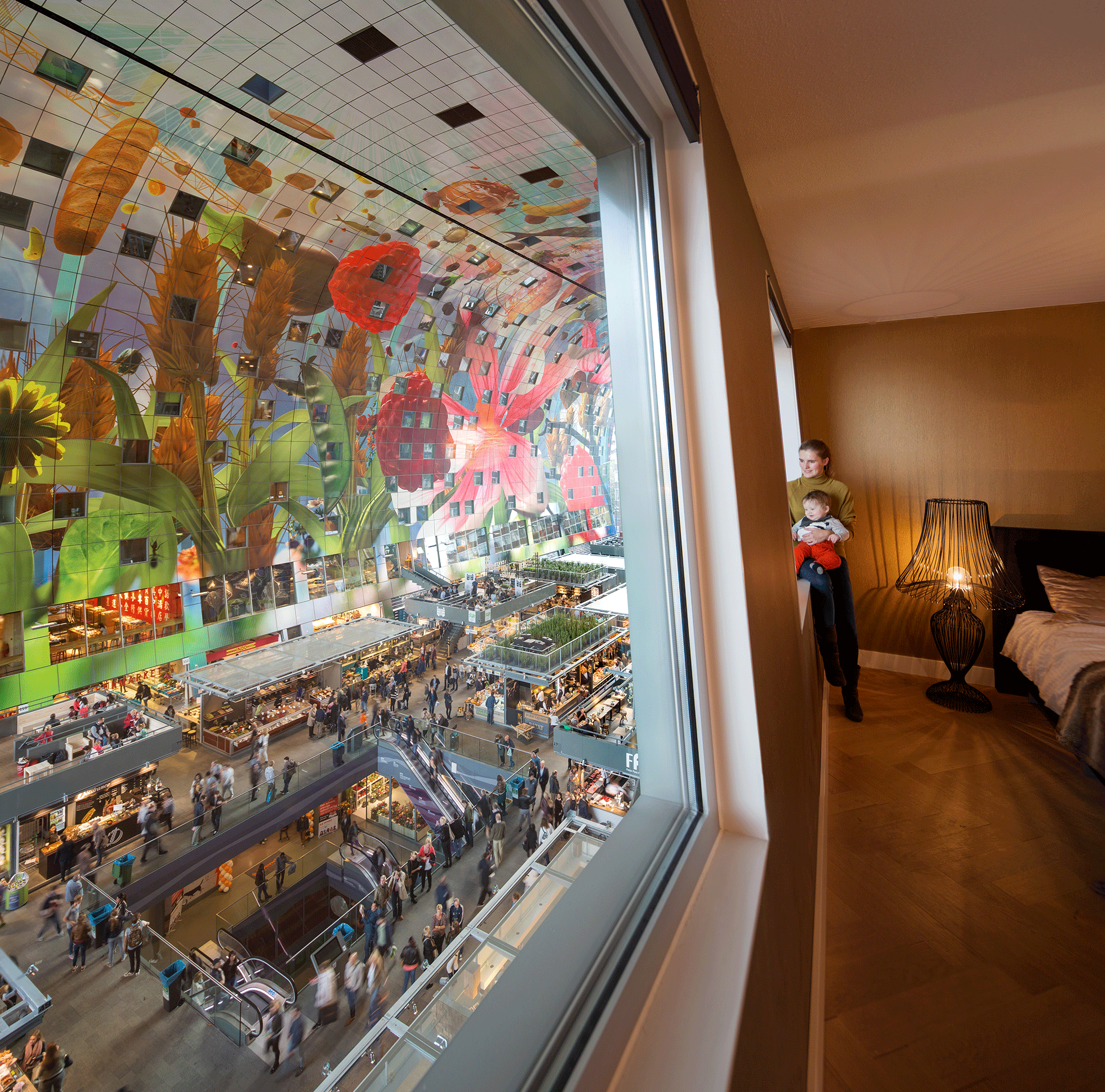

Arno Coenen and Iris Roskam. Photo: Daria Scagliola/Stijn Brakkee.

Nieuw Leyden speaks of a ‘Dutch morality’ that MVRDV brings to all their work and a sense of generosity and egalitarianism, whether the project is in China, India, South Korea, France, Poland or the Netherlands. In their urban plan TEDA Urban Fabric, MVRDV adapted the Dutch row-house typology to the local context and development economics of Tianjin, China. At ground level, the development appears like a typical Dutch housing development with neat brown brick housing of three to four stories and human-scale public spaces in between that allow for gathering and interaction. But, to achieve the density required of a rapid growth Chinese city, slender towers are dotted throughout the urban fabric, spaced to allow for sunlight and views, each with their own plaza.

By including high-quality public spaces and decent sunlight access for each apartment or townhouse, this development creates its own amenity without having to rely on harbour views or parks provided by the city.

Another common theme in the practice’s housing projects is the desire to create ‘unprogrammed’ spaces that allow for communality. In Silodam and Parkrand, two housing projects in Amsterdam, MVRDV attempt to create smaller communities within the apartment complex by clustering different demographics or loose subcultures of people together around their unique shared space. This sense of individual and collective ownership gives vertical communities the conditions to flourish. Nathalie believes her interest in collectivity comes from studying modernist architects like the Smithsons and their collective Team 10, and her own teacher, Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger: “I particularly draw on Hertzberger’s approach to human behaviour. He told me once that whenever he ‘deliberately designed’ a place – a meeting point or a place where everyone is meant to gather – that it was not used so well. But, if he designed in a more relaxed way, these spaces would come to be used very well, you know? Sometimes it’s just better to let people make their own discoveries.”

As part of this experimentation into diverse modes of living, MVRDV think it is important to check-in with the inhabitants of their housing projects after they have been completed to see how real life in these spaces unfolds. Because as Nathalie mentions, “There are people living in these experiments.” MVRDV work with a photographer to document the interiors of their completed projects, with many of these photographs collected in the monograph MVRDV Buildings.

“We started with the housing for elderly where we documented the building in a very systematic way with a Dutch photographer,” Nathalie explains. “He went to each house before people moved in, opened every door and made a picture. There are roughly 100 different houses but all the windows are slightly different, there are different coloured balconies. And then after people moved in, he went back and did it all again: opened the doors, take a photograph. And you could sort of put the empty and the used version next to each other, so instead of this enormous repetition, you would see all these different interiors. Because that’s the final test – what the people do.”

The work of MVRDV can seem contradictory at times; it can be whimsical, loud, and provocative, challenging our expectations of what architecture and the city can be. But there is a humanist undercurrent to their work, a grounded, reflective and deeply practical understanding of how people interact in space. When asked how MVRDV’s way of working could translate to the Australian context of planning controls and developer demands, Nathalie jokes, “Indeed, would we be able to survive the jungle here?” But, it is interesting to consider what a bit of Dutch morality could bring to Melbourne, how we could more consciously construct new or re-imagined parts of our city. Meanwhile, MVRDV continue to set the scene for the future of our cities, defining new typologies for multi-level communities and humanistic architecture in a post-nature world.

Many thanks to Natalie de Vries and MVRDV for speaking to us about their human-centred design, and to regular contributor Katherine Sundermann for her wonderful words.