D.I.R.T. Studio defies ecological dualism

Landscape architect Julie Bargmann creates places that defy traditional notions of nature and beauty. To her, a landscape represents the intertwining of social and ecological cycles, over time. “I’ve always dismissed any kind of dualism or binary system”, she says. “It’s one long evolutionary line – how the landscape is evolving.” Through her work, the pastoral ‘ideal’ is revealed as a cultural construct, as ‘natural’ as a quarry, a landfill or an old car factory. Emily Wong speaks to Julie Bargmann about how she uses ‘toxic beauty’ to transform industrial sites into 21st-century public spaces with a past, present and future.

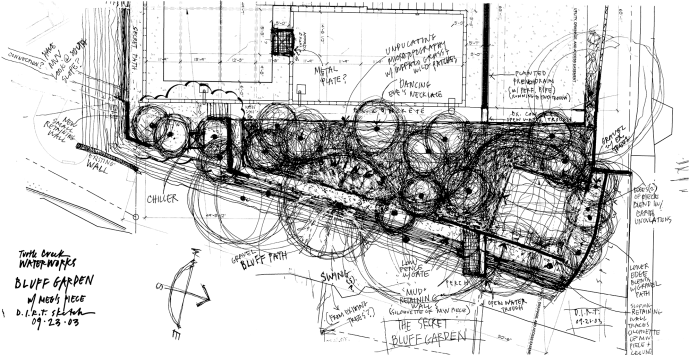

To understand the work of Virginia-based Bargmann and her tiny studio D.I.R.T (Dump It Right There) means thinking about nature not only in an expanded sense, but also on an expanded scale. “I see the kinds of [industrial] landscapes I work with as on a continuum”, she says. “Clients [tell me to] get it back to nature’. And I’m like, ‘Uh, it is nature!’ A historian I once worked with on Vintondale Reclamation Park described the design intent as finishing the work of the past labourers.” A description Bargmann felt was apt: “If we look at a map of geological time, our human impact on the site is just a blip, another turn. [History has] always been tweaked to go in different directions, so now we’re just pushing it.”

Vintondale Reclamation Park was one of Bargmann’s first projects and one that set a precedent in the wave of ‘90s post-industrial design that was to follow. In a corner of Vintondale, Pennsylvania, in the Appalachian Mountains, Bargmann teamed up with artists, a historian, a hydrologist and the town’s locals to create a public park that vivifies the purification process of acid mine drainage, a toxic legacy of the area’s now defunct coal mining industry. The park features a series of linked filtration ponds fringed by trees whose autumn foliage mirrors the colours of the water in each successive pool. In the first pond, the water is a toxic red; by the sixth and final pond, a pure and neutral blue. “A big part of what one does with those landscapes is make sure they don’t kill anybody,” Bargmann explains. “So, you get rid of the danger, and then…? Well, you accept the landscape for what it is.”

While an early work, Vintondale Reclamation Park epitomises Bargmann’s ongoing approach. She focuses on creating spaces that engage rather than mask past and present realities. Take the Urban Outfitters Headquarters in Philadelphia, a hub of corporate offices and design studios that Bargmann designed on the site of a former US navy yard. Here, Bargmann used concrete salvaged from the original ship-building operations to create new terraces for the campus grounds. Aside from kicking goals on the sustainability front (re-using existing site materials not only avoids landfill, but also means they don’t have to be transported off-site), for Bargmann, it’s about the narrative of cultural and ecological history within the site’s present and future – the patina of time. “With every landscape, [if] you’re a designer, you should create a narrative. But I find with these [landscapes] especially, they need a narrative.”

Recycling debris, ‘daylighting’ the landscape process (as at Vintondale Reclamation Park) and revealing forms are all part of Bargmann’s wider mission: to create landscapes that aren’t just about putting a band-aid on ugly or dangerous places, but about encouraging visitors to engage with sites in more complex emotional and intellectual ways. In part, this is to do with beauty – a concept that Bargmann has worked to expand since the early ‘90s. While now, two decades later, the post-industrial aesthetic has mostly been normalised (“It’s even got right to the point of being ‘cool’”, says Bargmann, wryly), it wasn’t always so. Bargmann coined the phrase ‘toxic beauty’ to describe her particular blend of the strange and the sublime. What she proposed – that these ‘damaged’ sites with their rusting structures and poisonous soils could actually be beautiful – was controversial. What turned the tides? Bargmann puts much of it down to the passing of time. “When I [first] started teaching, I used the work of photographers like [Edward] Burtynsky as a way to bring industrial landscapes into view”, she says. “And I used them for shock effect. And then after a while, the students started to be like, ‘What’s your problem?’. So just by virtue of [these landscapes] coming into view, and then environmental regulations kicking in in the ‘70s… kids born after that grew up with an environmental crisis and the idea of the environment having rights.”

‘Blighted’ and ‘tarnished’ are somewhat dirty words for Bargmann, yet they’re words often put into use by the wider public to describe the kinds of sites with which she works. For Bargmann, it’s all about the connotations: a site may be polluted or contaminated, but whether it’s blighted or tarnished, she argues, is a matter of perspective. Bargmann is a glass-half-full character – in her language, vacant land becomes fallow (dormant but waiting); instead of remediating ground, one catalyses its potential. “The ‘re’ words are so retro” she insists, although ‘regenerate’ may be the exception. “I use it in the sense of creating something new”.

The late Robert Smithson is someone whose name surfaces often during our conversation. A leading protagonist of the ‘70s land art movement, Smithson’s influences on Bargmann are many and deep. Smithson photographed New Jersey’s industrial ruins (‘monuments’ he called them) and built his most famous work Spiral Jetty in Utah’s Great Salt Lake – an eternal work-in-progress. Bargmann, originally a Jersey girl herself, trained first as a sculptor (she has an undergraduate degree in fine arts) but soon became frustrated with the making of ‘objects’. In the work of Smithson, other land artists and post-minimalists like Eva Hesse, she found that the true intention was not the product or the form, but the experience. “I knew, even when I was finishing [art] school out in Pittsburgh, that I wanted to make work like the land artists, but in much larger contexts”, she recalls. “To use form as a verb instead of a noun.”

Whether it’s a once active quarry or a working Ford manufacturing plant, each site presents its own unique challenges. Bargmann champions multidisciplinary collaboration – she lists consultants and collaborators on her studio’s website, although she also admits, “We need to update our website!”. Among the regulars are many ‘ists’: artists, hydrologists, biologists, ecologists; but also soil engineers, architects, fellow landscape architects, whole communities and – it should come as no surprise now – historians. The ability to draw from this fertile pool of expertise is why, Bargmann asserts, D.I.RT. will always be small. “I really resist this whole idea that landscape architects – while we’re synthetic thinkers – can do it all.” Bargmann believes that it’s the back-and-forth of perspectives, ideas and fields that leads to the most unusual and compelling outcomes. This of course, depends on finding “good engineers [and other experts] who are willing to play… who aren’t trapped in doing things the usual way. And that usually takes a person who’s curious.”

Grit, determination and a penchant for speaking her mind have long defined Bargmann’s reputation in the wider community. This can sometimes mean that projects don’t get finished – at least not by D.I.R.T. “We get fired a lot”, she says. “You can count the number of our built projects on one hand.” Despite obvious frustrations, she’s adamant that being a designer means “getting in there politically – to talk, challenge and ask questions about the distribution of resources. ‘Why is this going there?’ It’s about asking the difficult questions that have to do with defining and framing the project itself.”

When not hassling mayors and developers as D.I.R.T, Bargmann is associate professor and chair at the University of Virginia – where she’s enthusiastic about ‘contaminating’ (her words) the next wave of young designers and agitators. Teaching is something she takes great pleasure in; it brings its own set of rewards. “I’m starting to see [former] students moving into positions now where they’re making more decisions”, she says. “It’s very cool. It’s totally happening! What’s more, projects are coming up and the good news is that landscape architects are being asked to lead them. Not engineers, not architects – landscape architects. How cool is that?”

We thank Julie Bargmann for taking us inside the world of D.I.R.T. Studio, and former AP editorial assistant (and landscape architect!) Emily Wong for her words. To keep up with D.I.R.T.’s current projects, check out dirtstudio.com.