Keiji Ashizawa on rebuilding a less-fragile future

Keiji Ashizawa’s hats are many. As an architect, product designer and erstwhile steel fabricator, his work spans vast luxury residences to tiny tealight holders. There’s a common vernacular no matter the size or context – a lightness and conciseness informed by Japanese simplicity, modernist pragmatism and a deep understanding of his materials. Keiji’s triumphs in the built environment include the award-winning Wall House – an ocean-side oasis for the high priest of Japanese fashion, Issey Miyake, which he designed in collaboration with Australian architect Peter Stutchbury. His furniture and lighting has been exhibited all over the world, and recently he was commissioned by Swedish DIY behemoth IKEA to contribute a space-saving design to their PS collection. Among his many plaudits, Keiji is the founder of the Ishinomaki Laboratory – a community DIY workshop he initiated in the wake of the Great Tohoku Earthquake, where local people could come together and begin to build their post-disaster future – one red cedar 2×4 at a time.

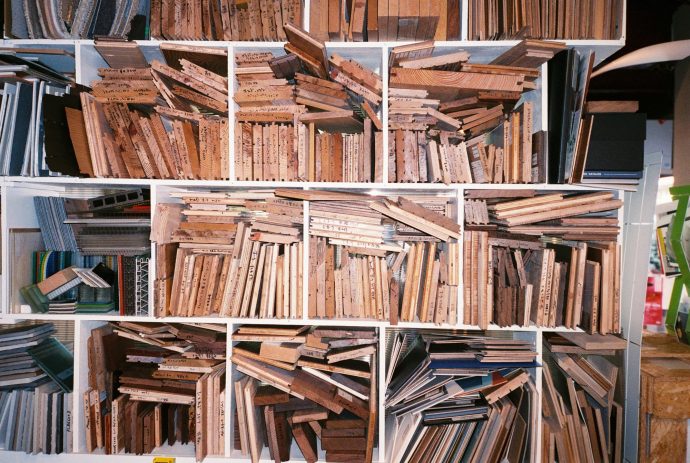

I visited Keiji last autumn, finding him in the “real-Tokyo” Bunkyo area of the megalopolis, where ramshackle row houses bunch up around Edo-era temples and shrines, barely a humming neon in sight. His studio is a tiny crammed-full monument to past and current endeavours – houses in miniature form, waves of steel lighting billowing overhead, the meeting nook encircled by families of pipeknot furniture and sliding box drawers, while clusters of Ishinomaki stools and benches huddle just outside. Every sill and shelf is overflowing with samples of timber, steel, stone – materials waiting to be written into a story.

Keiji creates his language through practice. He advocates a singular materiality wherever possible, forming a relationship with the material by applying the same idea, iteratively, to different shapes and situations over time. Three welded steel pipes led to the pipeknot, a simple joining system Keiji first used to construct a three-pronged standing timber hanger, then a table, then a coffee table, until finally informing his design for Ikea. “If it’s a good design, somehow I have to design everything.”

Of all Keiji’s projects, the one that compelled me to track him down is the Ishinomaki Laboratory. Last year the initiative proudly celebrated its commercial incorporation as the “world’s first DIY label”, with many international designers having now contributed designs to the collection of pleasingly utilitarian furniture. When we last spoke Keiji was freshly returned from this year’s Salone del Mobile in Milan, where he had exhibited Ishinomaki Laboratory products alongside German designer Sebastian Herkner and Czech blown-glass manufacturer Verreum (of which Herkner is art director).

The Ishinomaki trajectory began with a phone call from a friend and former client, ten anxiety-stricken days after disaster struck. “I had no idea if he was alive or dead,” says Keiji, “Even in such a modern city, everything is lost in such a big tsunami. There is no connection, no way of contacting.” Ishinomaki, on the Miyagi coast north of Sendai, was one of the most severely affected cities – battered repeatedly by tsunamis up to ten metres in height. More than 29,000 homes were destroyed and 3,097 lives were lost, with a further 2,770 still not accounted for.

When the friend finally got through it was to ask for help in rebuilding, and Keiji immediately sprung to action. He assembled a force of architect and designer friends to join him in Ishinomaki, forming a small committee with local business owners, city planners, researchers, digital strategists and students dedicated to dreaming up Ishinomaki 2.0. They met daily above a restaurant that had been destroyed by a rogue boat, working to establish the blueprint for the city’s urban renewal strategy.

To Keiji, design is the ultimate “survival skill”, one that has helped him solve numerous ‘problems’ in everyday life – a new studio with no desks; an impromptu dinner with no table; an international exhibition that needs to be installed in a day. Whatever needs doing, he does himself (or with his colleagues), using the materials he has lying around. In Ishinomaki, Keiji could see that those people who were DIYing their houses and shops were rebuilding faster than those waiting for government assistance, but not everyone had the skills or the confidence to do it themselves. His idea was that an all-welcome community workshop could inspire more people to get hands-on by providing simple techniques and ideas for furniture that might “make life easier or nicer”.

Before it could offer a utility, the Ishinomaki Laboratory first set about coaxing the community out to connect with one another again. Fragile after the loss and wreckage of the tsunami, many people had retreated to private spaces and needed a specific reason to congregate. A free open-air cinema was the catalyst to explore the first product – the Ishinomaki Bench, a sturdy (yet easy to assemble) two-seater made from outdoor-appropriate red cedar. Making en masse required multiple hands on the job – Keiji enlisted the help of local high school students, whose enjoyment of the task then carried up through the generations. “When we invite young people, at the same time, older people come because they really want to help in our mission.” More than forty benches were made in two days.

Encircling the cinema screen, the seating created a new social topography that encouraged interaction and enjoyment. Volunteers (young and old) were proud of their handiwork and excited to share their experience with others. Acknowledging the scarcity of furniture in government-issued recovery housing, the benches remained after the festival – a nudge to townspeople to come back and take them home. Before long, the Ishinomaki Laboratory stamp had its place (and was excitedly talked about) around tables and on curbs all over town.

The Ishinomaki Laboratory formed swiftly – hanging the sign on their first workshop only four months after the quake – and products were designed and made at breakneck speed, responding with urgency to the needs of the city. Keiji’s initial ‘in’ with the locals was a crucial kick-start, but the long-term efficacy of the workshop depended on co-opting the community as ambassadors of its purpose. The affable Chiba-san – handyman enthusiast turned official lab leader – was and still is a huge part of this process. A former sushi chef who tragically lost his mother (and his restaurant) to the tsunami, Chiba’s post-disaster outlook is philosophical: “If you survive by luck, you must live, as you are not dead,” he insisted, when interviewed for a short documentary made about the workshop. Chiba’s new way of living meant leaving sushi behind, becoming the chief custodian of the workshop’s communal culture and a conduit between lab founders and the townspeople.

Four years since its inception, Keiji says the Ishinomaki Laboratory now “almost perfectly fits in the local area” and is well on its way to self-sufficiency. Many local people are employed, with an ongoing exchange of people and ideas between Tokyo and Ishinomaki. Next month, Keiji will visit with a group of Japanese and Swiss designers in tow, to run talks and workshops for the community. The workshop is still free and open to the public, supported by a stream of fit-out commissions from local businesses and the international success of the ever-expanding repertoire of everyday furniture.

“A good design is modest, has a long life, and works in any situation,” says Keiji. The Ishinomaki products were born out of a local emergency, but their ultimate mission – to create enjoyment through everyday use – resonates far and beyond. Bahbek Hashemi-Nezhad’s Dinu stool that encourages a casual lean; TORAFU Architects’ skydeck that affixes to hand rails to create an instant perch; Tomás Alonso’s ‘ma’ set of stools and table that slot comfortably within one another; Julian Patterson’s lean-to shelf; Tomoko Azumi’s carry stool – all are portable expressions of social scenery that first found their voice in Ishinomaki. They are familiar fixtures – hinting at objects already at home in sushi restaurants and izakayas and public parks – but in many ways it’s this familiarity that makes them so distinct. Each seat and surface is embedded with stories of townspeople working together; conversations shared while imagining a rosier future.

We are constantly inspired by powerful, simple ideas that create and strengthen communities, of which the Ishinomaki Laboratory is a shining example. You can find Ishinomaki furniture stocked at Apato in Melbourne, currently the only Australian stockist. Huge thanks to Keiji for hosting us in Tokyo and showing us around his studio and beyond – our minds were blown. Thanks also to the band of talented photographers who helped illustrate the story – Fuminari Yoshitsugu, Rachel Elliot-Jones and especially Paul Barbera, who shared with us images of Keiji’s studio he shot for his documentary photography project Where They Create. A very special mention goes to the team at Ishinomaki Laboratory, who were always quick to answer any questions we had along the way.