Clinton Murray’s House for Pam

With their signature timber facades, the residential projects of architect Clinton Murray remain quintessentially of the Australian coastal spirit. Both borrowing from, and camouflaging with, their often-natural surroundings, he creates homes that recall the history and texture of the bush – not least because reclaimed timber is his material of choice. While his affinity for natural materials always dictated the direction of his commissions, it wasn’t until Murray designed and built his own home in 2001 (a loving ode to his wife, Pam) that he truly felt he understood the nature of his medium. Jack Patrick Garner takes a look at where the self-effacing Murray has come from, his love of lumber, and his ‘House for Pam’.

Clinton Murray was born to build. Three generations before him, his great-grandfather began a building company that would employ the Murray sons and eventually lead to his father project managing – and his brother building – much of Clinton’s early southern coastal work. Having grown up in Ballarat, he studied Architecture at Deakin University in Geelong. He claims the first AFL game he ever saw, at age five, was a life-changing experience, and that he isn’t immune to a tear or two to John Williamson’s ‘True Blue’ – not the typical admissions of your erudite architect. From the early ‘90s to mid-2000s Clinton, as a sole practitioner, designed a series of homes predominantly along Australia’s east coast.

In this coastal domain he developed both a tactile and sentimental tie to the use of reclaimed timber, which has since become the signature of his residential portfolio. “The character and quality of reclaimed timber is underpinned by the story. Can you imagine in 1940 camping in the bush in Gippsland and cutting, by hand with a broad axe, a 500mm x 215mm x 6-metre piece of timber? Think of the incredible physical effort required. Think of the heat or cold. Think of the flies and mosquitoes. Think of the campfires. I see tough men with beards smoking pipes telling stories. What do you see?”

His embrace of recycled and reclaimed materials well preceded ‘green’ architecture coming into vogue and emphasised his affinity for quality design and longevity over arbitrary trends. Clinton’s work – through design, choice of materials, and a sensibility informed by the surrounding landscape – creates a dialogue between the built and natural environment that resonates in a powerful manner. “I fell in love with a stockpile of old timber and never looked back. [They were] beams cut out of the Gippsland bush. The guy we bought the timber from for our first house said: ‘They should be in a bloody museum,’ and he was right. You have to consider that largely up until the early ‘90s, timber from demolished buildings and structures around Australia was either burnt or taken to the local tip.”

His passion goes well beyond simply pulling perfect boards off the woodpile however. “Given the materials have a ‘life of their own’, they can force you to compromise. For example it’s hard to find ‘big gear’ that’s longer than six metres. Timber sections greater than 300 x 300 are rare. You obviously can’t pick and choose species and exact dimensions. Re-machining is often required and can be problematic.”

It took half a decade, but in 2000 Clinton was eventually ready to source some timber for himself and hoist it up as the shell of a family home in the beautiful seaside town of Merimbula, New South Wales. “Designing your own home is a frightening experience – being frozen in a moment in time! I’ve never had a desire for the whole ‘architectural experience’. My wife Pam had other ideas and questioned why everyone else got to benefit from my architecture while we lived in an uninspiring rental house. House for Pam revealed itself after about 30 designs. While my other residential projects at this time were relatively simple in form, House for Pam really became brutally simple: one horizontal timber box juxtaposed by a vertical timber box.”

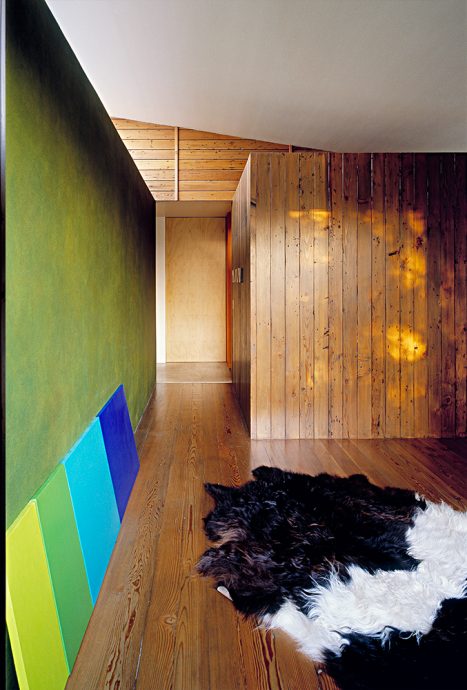

The focus on the residence was living simply, with a shared bedroom for his four boys, a single bathroom, a main living area and a tower retreat. His one oversight, and one he is yet to live down, is forgetting a laundry. The beautiful façade cladding and internal lining and floors were 140 x 40cm tongue-and-groove Oregon timber salvaged from the ceiling of a 1940s Australian tyre factory. The Oregon was “shipbuilding” quality – with the tighter grain pieces being handpicked for the external cladding. All boards had to be cleaned, deloused and sanded down by hand. For some, it was easier to imagine the house in concrete. For Clinton, timber has a texture, story and smell that no other material can replicate.

For Clinton the project was a hugely positive experience; so much so the family made it their home for over 12 years. “I underestimated just how fantastic it is to live in such a ‘personal’ house. While it’s pleasantly surprising to experience things you’d planned actually working, the real joy comes from the unknowns. The home has its own spirit. We sold the house last year to people who love it and have treated it so kindly. They still call the home House for Pam and have been so generous in involving me in any changes they’ve made.”

With this confidence in his medium, Clinton has continued to source materials from wood stacks and demolition yards around the country. His more recent Fairhaven residential project was clad in timber salvaged from the EJ Whitten Bridge-build in Melbourne. In similar style, Bungan Beach in Sydney’s northern beaches is skinned in wandoo pulled from the floors of an old wool store in Western Australia. Those who commission him share his sentiment. “Clients love to be part of the new story of the timber. They’re the custodians. When Overcliffe was sold some years back it was a very emotional moment for the client and me.”

It’s not hard to see why natural materials could be an attractive choice. However, influence for Clinton has come from a variety of sources. “As a kid I was struck by the way things were and liked to question things, most times internally. Why did the window in our sunroom in Ballarat not go all the way to the floor? Why did my father cover the beautiful Jarrah floorboards with ‘Great Barrier Reef’ carpet’? I had a great mentor in an older, nicely unhinged brother. He taught me that there is beauty (design!) in all things.” Clinton’s work also makes reference to Robyn Boyd’s award-winning Black Dolphin Motor Inn, which incidentally is located close to House for Pam in Merimbula but has since been renovated. Like Clinton’s work, The Black Dolphin’s exposed timber columns similarly echo a oneness with the surrounding tracts of bushland.

After 12 years in Merimbula, Clinton and family moved back down to Melbourne where he now works as Design Director at Jacobs Engineering (formerly SKM, formerly S2F), moving into public rather than residential architecture. In this time his focus has shifted onto larger scale public buildings and community projects, on which his residential background has given him a good footing. “The simple difference is that public architecture impacts on the lives of many people. In that sense the stakes are much higher. Dealing with the complexities and nuance of residential architecture is a solid apprenticeship for designing public buildings.”

For Clinton Murray the sentiment remains clear: “It’s uncomplicated. Be thorough. Be strong with your ideas. Avoid fashion. Avoid the arbitrary. Your eyes and ears tell you you’re living in a time when we all have to be really honest about the resources we’re using. We all share the responsibility of treating the earth preciously.”

He closes with a final thought on House for Pam: “House for Pam had lots of fans and some detractors too. There was the occasional drive by ‘flattery’. A favourite was: ‘That’s the ugliest house I’ve ever seen.’ I would only ever smile and pause for a moment to reflect how beautiful their own homes might be!”

Thanks to Clinton Murray for chatting with us about his wonderful House for Pam. Images have been provided both by Shannon McGrath and courtesy of Clinton Murray Architects.