Michael Madsen Interview: Halden Prison

In the mid 2000s, the Norwegian government staged a competition for the design of a new, high-security facility to house some of Norway’s worst criminals. Completed in 2010, the complex, known as Halden Prison (or Halden Fengsel), has received much exposure both for its architecture and its practices – quickly garnering the tagline (from Time Magazine, The Guardian and numerous other sources) as the ‘world’s most humane prison’, it’s also been shortlisted for, and won, numerous design and architecture awards around the world. Currently in its fourth year, the complex, which aspires to be “light and positive”, is also home to around 250 of Norway’s most notorious offenders, including Anders Breivik, responsible for one of the country’s most recent mass killings.

This is the complex that forms the subject of Danish filmmaker, Michael Madsen’s contribution to Cathedrals of Culture – a six-part documentary now screening at ACMI, that sees six illustrious filmmakers given the opportunity to explore a significant, European architectural structure of their choice. This is the second ‘architectural’ film by Madsen, whose 2010 documentary Into Eternity delved into the myriad issues surrounding the construction of a nuclear waste storage facility in Finland.

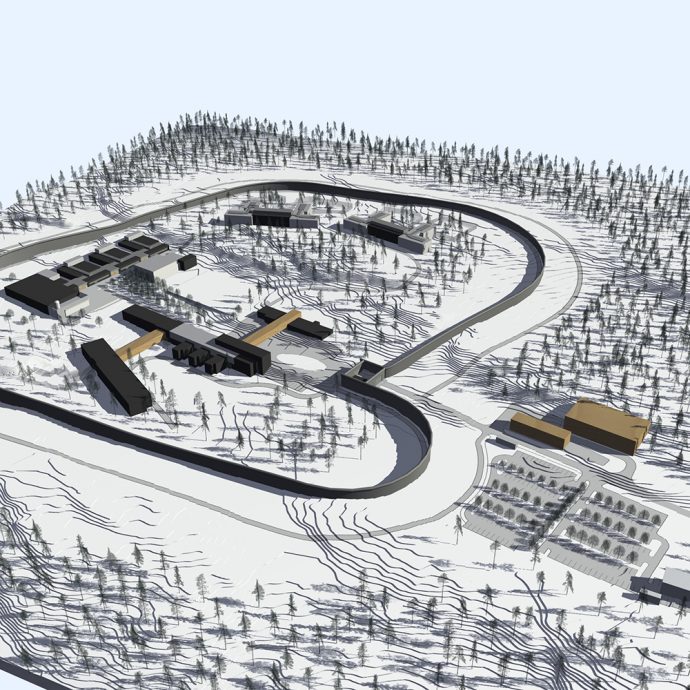

Halden, located in Ostfold, south of Norway, is a reinterpretation of the traditional typology of the prison. Conceived by Norwegian architecture firms Erik Møller Arkitekter and HLM Architects, the complex is a place of contrasts, reflecting the tension between Scandinavian ideals of rehabilitation and the loss of freedom associated with transgression.

Laid out as a small village, each function of the prison is contained within a separate building, forcing inmates to move around the space like one would a town. In addition to the diversity of interior living spaces, shared kitchens and exercise yards filled with artworks and sculptures, there are running tracks that wind through the wooded landscape. The aim is to emulate the living of a normal life as much as possible, to prepare the inmates for their future return to society.

A palette of materials both organic and man-made, blend the complex into, and provide a counterpoint with, its natural surrounds. Untreated wood, dark brick and granite reflect the complex’s setting within a picturesque woodland of birch forest, while concrete, glass and galvanised steel mirror and extend the weather conditions of the sky. Set against the naturally undulating Norwegian landscape, the long, vertical windows of the simple, monolithic buildings gather sunlight and lure the outside in, creating luminous spaces of warmth, which evolve over the course of the day and the year.

At the heart of Halden’s design lies a heightened and measured consciousness of time – one that emphasises the turning of the seasons, the rhythms of life and ageing. Reinforcing the belief that reflection and the accumulation of experience are viewed as key elements in the rehabilitation process.

Complementing the physical forms of the complex are the practices that take place within it. Cooking classes, horse-riding, sporting activities and music lessons facilitate the learning of new skills, while interactions between inmates and staff are grounded in a philosophy of mutual dignity and respect.

In conjunction with the release of Cathedrals of Culture at ACMI, Emily Sia Lian Wong sits down with Michael to learn more about his interest in Halden Prison, architecture, and his unique and poetic approach to documentary-making.

EW: Where does your interest in architecture come from?

MM: I trained as an architect earlier on, in my twenties. I now work with sculpture, and the physical modulation of this world is something that interests me.

How did you come to be involved with the Cathedrals of Culture series?

I was the first one invited to participate in the Cathedrals of Culture series because Wim Wenders [the director] had seen Into Eternity [Madsen’s first feature-length documentary] and thought it had a lot to do with architecture.

Why did you choose a prison as the subject of your segment? Why Halden Prison?

[Wim Wenders] said they were thinking in terms of concert halls and museums, and that seemed like an obvious choice, but I thought perhaps there was another way of interpreting the meaning of a ‘cultural cathedral’. This is why I chose the prison in Norway. In terms of architecture – concert houses and museums are all landmark buildings and cultural manifestations. They are public buildings that are a celebration of a culture in many ways – they are meant to be very visible. They are all built with the idea of educating the general public, a kind of public service.

I’m more interested to look at some of the other angles of society, like a prison that has the ideal of re-socialisation, as is the case of Halden. In that case, perhaps it’s a different kind of public service that’s being provided, but one that’s even more interesting because this is the place you put the people who can’t be a part of society – it’s the flipside of society.

What were some of the other structures you considered when pitching buildings for the film?

I was actually considering the Opera House in Sydney because I have a sister living in Sydney and have been to the Opera House several times – it’s a magnificent building. I think that even if I’d had the chance to make a film about the Opera House, I probably would’ve reached the same conclusion – that it’s more interesting to look at the flipside of society and also to examine a building, the physical appearance of which should be anything but spectacular. I also wanted to take the audience into a place where they couldn’t ordinarily go.

In your earlier film, Into Eternity, concerning the construction of a nuclear waste facility in Finland, you seem to use architecture as a backdrop for raising questions about what it means to be human. Could you explain this approach and is it an approach that you continue with in Halden Prison?

Yes, I think you could say that about Into Eternity, which looks at a facility that might be the first post-human structure ever to be built – certainly it’s thought of as a building intended to outlast civilisation as we know it. The basic construction principle behind the Onkalo facility – this bunker-like structure – is to hide it, to let it slip into oblivion. When you have such a radical strategy in terms of any building it is because you don’t trust what we humans could be interested in doing in the future, either out of curiosity or out of malign intent. Into Eternity is really about whether we humans can trust ourselves. If we don’t trust what we might want to do in the future, and we fear what we might simply out of curiosity want to pick up, then of course a facility like Onkalo is not really about a technological problem but about our own nature.

In Halden Prison I look at the facility as a kind of rehabilitation technology. Everything in that building from the colour scheme and the choice of materials to the spatialisation and the selection of – everything is aimed at social rehabilitation. Everything, in other words, is a radical attempt at shaping human beings. The idea is that the person who enters should be a better person when they get out. That idea of molding a human being, of emulating normality inside the walls just as it is outside that model world is an idea that I find very interesting. This is a building that looks just like an old person’s home or a public school in the country – it’s only the [8m high] ring wall around it that gives it away.

There is no less amount of power in a building like this than there was in a prison of a hundred years ago, which would have been designed as a fortress. In such buildings, the public statement was the state’s display of power. At Halden it’s a different strategy and there are very specific reasons why power decides to camouflage itself as an old people’s home.

Could you explain the film’s opening quote from Michael Foucault, that prisons all resemble factories, barracks, hospitals, which in turn all resemble prisons?

I find Foucault’s work extremely interesting in that he [like myself] also tries to look at this world as a phenomena – what is society? He looks at the fringes of society – the history of prisons, the history of madness – and he attempts to decipher how society or normality defines itself, creates itself, by creating outcasts, by designating something as outside of normality. If you look at a school or a military barracks or a prison or a hospital, there are similarities. And I think he would say that the reasons why these similarities exist is because [all these buildings] are machines of power, they all exercise the power of the people who govern these institutions. I think he would say that there’s really no difference in the nature of the power, only in the way it’s being exercised and displayed. Power once took the form of physical punishment, but now power is much more elusive – modern power works in such a way that you think you’re controlling yourself, you think that you’re free. But you act according to certain things that you aren’t even really aware of. I think Foucault would say that if you looked at the architecture of modern society you can see these similarities, and while you might interpret the buildings as completely different things, they are not necessarily so.

[Like a prison], an opera house also has the intention of shaping citizens in a certain way (in the case of the opera house, based on art, which is considered to be good). It’s the intention of shaping people that is the same in the opera house as in the prison, and the question it raises is – who is entitled to perform that shaping? Also why this particular way of shaping people? Who knows if this is the best way? That’s the huge question, of course.

Halden Prison and Into Eternity are not what would ordinarily be described as traditional or architectural documentaries, with very few technical specifications, lists of construction materials and explanations of engineering. Could you explain your particular approach?

I try to look at things as phenomena. If we have a facility like the Onkalo bunker or this prison – what is this building an expression of? What does it express in terms of the society I live in? I don’t have an opinion as to whether the prison is good or bad or nuclear waste is good or bad, I simply try to understand how these structures work, what is the intention behind the facility and how is this intention potentially realised. Much of my camera work is developed based on this approach – if I was an alien coming to this world and couldn’t understand anything, what would I be looking at? I try to forget what I know so that I can perhaps rid myself of some of my preconceptions about this world.

Your film draws attention to the paradoxical nature of Halden Prison, a place that aims to rehabilitate but by its very nature of imprisoning, is a punishment. In your opinion can this contradiction ever be resolved and is it possible for a prison to be humane?

I don’t really know what ‘humane’ means, to give a sort of polemic answer. But the problem any society has is what happens if you don’t want to act like the majority or as the few in power think you should be acting – what do you do? I think that the exercise of power in terms of locking people away is perhaps simply impossible to avoid, and the question of whether that is ‘humane’ depends on whether we are talking about humane for society or for the criminals.

The core principle in Norway, that even if you are a criminal that of course you’re still a human being, and that because you’re a human being you deserve to be treated with dignity and respect, is extremely important. Otherwise you alienate people which is even worse and I think there are a lot of problems in the world with alienating people. In Halden Prison they try to show respect and to give dignity and perhaps thereby to build up the people who go to prison. Many of these people, at least in Norwegian society, have had a very difficult life. It’s not strange that they have ended up in prison, and there’s an awareness of this, which is very important.

Cathedrals of Culture, “a film project in 3D about the soul of buildings”, screens at ACMI from 28 October – 11 November 2014, in association with MPavilion. Thanks to Michael Madsen for making his tme available for this interview. Images come courtesy of Erik Møller Arkitekter and ACMI. Also, if architecture documentaries are your thing, have a look for the Living Architectures series, which touchingly documents the lives of people who live and work in some of the world’s most famous buildings.