The local in the global: Future Living Studio

In 2013 as a part of the UN Environmental Program, designer Philippa Abbott spent four months in Vietnam working on a Sustainable Product Innovation Network (SPIN) project – the third iteration of The Future Living Studio. Collaborating with a team of Vietnamese, French and German designers, the team worked to develop a body of applied research and a collection of workplace furniture that showcased local techniques, materials and cultural context while implementing best-practice sustainable design techniques. This project aimed to bring global design knowledge and innovation into a very local and specific context, developing pathways to ecologically conscious design for the Vietnamese market. In the following article, Philippa reflects on one part of the co-design process, a few weeks in May 2013 in which she collaborated directly with Vietnamese craftspeople without shared language.

Each morning at sunrise, French textile designer Audrey Charles and I would ride our motorbikes out of Hanoi into one of the thousand surrounding craft villages. Each village specialises in a certain way of making and a specific material: bamboo, rattan, ceramics, textiles, hardwood and grasses, to name a few. As we rode, the hum and dense chaos of the old city and its street-side living gradually slipped away, replaced by monolithic residential and commercial towers and large carriageways under construction. On the outskirts of the city the soaring population is truly apparent, as is the rate of urban development – a concrete tsunami swallowing everything in its path. This is quite a recent phenomenon in Vietnam, but many craft villages have already been absorbed by the bulging city limits and artisans can now be found down back alleyways between apartment blocks. We were working with a village that sat twenty minutes beyond the city limits (for now) – an hour and a half in honking, weaving traffic; a plethora of bikes avoiding the more and more common Land Rovers, Bentleys and larger more opulent vehicles.

As we neared the village which was our destination, the highway shifted into rice paddies and long vistas – the farmers tending to their crop; their homes a mixture of the vernacular wooden houses and newer concrete single frontages. The roadside became a continual stretch of marketplace for fruit, vegetables, furniture, tools and sheets of rice drying in the sun. We turned down a series of dirt tracks and arrived at our destination, Thanh Dat, a small factory with a specialisation in rattan bending and steaming. We had entered the next stage of making with Thanh Dat, a process that was both insightful and highly innovative. Up to this point the design team had been performing supply-chain analysis on a series of manufacturers with varying typologies of process – large industrial and small decentralised. The small decentralised factories are by far the most sustainable and scalable, both socially and environmentally.

The first step to designing was to understand the process of making and to draw inspiration from this. To watch and learn from the craftspeople, to understand the nuances of how they bent rattan, how much one can turn it and flex it and the infinite amount of possibility within the material. We worked closely with local craftspeople in one of these village factories using a technique that has been used for many hundreds, if not thousands of years. Central to this experience was the process of designing without any shared language. Collaborative design is usually very much a verbal process. A process of too-ing and fro-ing, confusion and clarity, of multiple creative wills and visions. Here, with no common verbal language, there was something very meaningful in collaborating with master craftsmen: to sketch together ideas; to use a shared understanding of tools, materials and a certain ‘making logic’ – an interactive and truly flexible process.

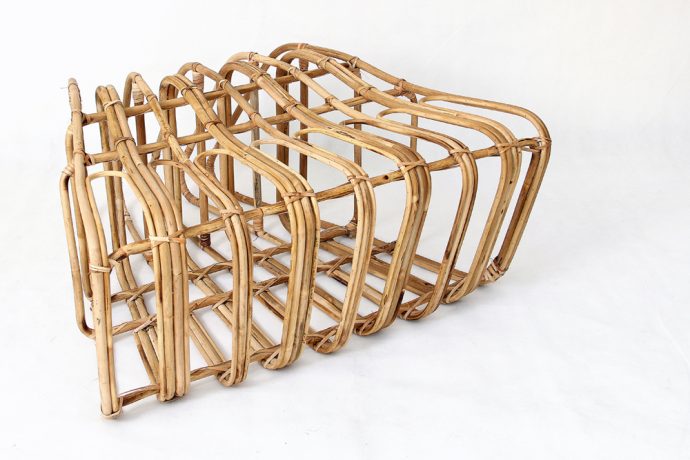

We started with a small sketch in my notebook and a pot of tea. Sitting in the corner of the factory, 43 degrees and sweltering, the sound of the nail guns popping a frenetic rhythm. I sketched out the base frame for a large ottoman and Mr. Long, the factory owner, pondered the sketch. I used my hands to explain that the frame would be replicated five times on an equally spaced angle. He stared at it, drank his tea, smoked his cigarette. He looked at me, nodded, took a drag on his cigarette and took the pencil, making a couple of changes to the frame pointing to the height and looking up at me. I gestured with my hand that it would be this height (400mm) and he tipped his head and wrote 500mm, and gave me a thumbs-up. I agreed. We drank more tea. This process continued for hours. We agreed, we shook hands and he explained it to the other craftsman. He smiled; he nodded his head in approval. The next day we would start. He would teach me the art of creating a frame (from old corks and ply) and bending the rattan. He would show me how to bind the frame and how to understand and utilise the material to its full capability. He and the other craftspeople would laugh at me – they thought it was crazy to make such an odd (in their eyes) form – our contemporary aesthetics differing greatly from their traditional Vietnamese style. However, throughout the days of working together, their respect and their appreciation for the piece of furniture grew as it simultaneously began to take form. The craftsmen advised on modularity, weighting, strengths and form. We agreed on the name ‘Sen’ – meaning lotus flower, a most auspicious symbol throughout Vietnamese culture.

We worked together for ten hours in the heat in unbearable humidity, compounded by the presence of a rattan steamer in the corner boiling away all day. We continued to ply the material and work together. These craftsmen had never made the 50km journey to Hanoi – this village is all they knew. The idea of fair trade, the 8-hour work day, safety standards and unions were all foreign concepts – they worked hard and long, they farmed, they provided for their family. The ideas we came up with regarding sustainability, design, innovation and contemporary aesthetics had no relevance to or resonance with their lives. However, issues of community, cost and time efficiency were mutually important and became the linkage between our two ways. Embedding ecological design principles throughout the process made it very clear that global standards of best practice sustainability methods are astoundingly close to old traditional and local ways of doing. Not only this, the more I embedded eco-design, the more economic sense it made for the factory – particularly in material usage and manufacturing time. Simpler was truly better. When doing a lifecycle analysis on the initial prototype, most aspects brought the design back to these old ways. What is lacking is the systematic structure that allows for multiple people and communities from many places to be involved in the production processes. With the advent of global communication technology this is very much possible – a global network of local villages.

At the end of each day we would order some local ‘fresh’ beer to say thank you to the craftsmen – it would come on the back of a motorbike in two jerry cans. We would lay down a mat on the factory floor, sit cross-legged in a circle and drink the beer (made daily) and eat dried squid. We would now try to communicate and make jokes, laughing at our own inability to understand each other. There was an intense curiosity to why Audrey and I were there. Kids would run through while geese wandered around the factory, dogs chased each other and cows grazed outside, elders tended to crops. It was a very good life, and definitely one worth protecting and valuing in the face of rapid urbanisation. Upon reflection, this local hands-on approach, and redefined design process, directly engaged people in their locale, which is the fundamental value of it. This is in stark contrast to the usual process employed in the Australian design industry: an intellectual concept, CAD files, trend- and consumer-driven manufacturing systems, and mandated technical drawings. Our experience was a human-centred process of making, connecting culture, materiality, tradition, local industry, personal experience and creativity. It supports people, a way of local living and a type of industry that is inherently good socially and environmentally. The project concluded with a seminar and exhibition that was televised nationally, which engaged the general public and also critically analysed the method, opportunities and pitfalls for designers working in Vietnam. The seminar involved representatives from the Vietnamese design community, expats and government who were presented with a full report upon conclusion of the project. One of the major conclusions from the seminar (which was wholeheartedly agreed by many specialists in the audience) is that Vietnam, and countries like it, need to build their design capacity, harness local skills and differentiate their export capability through local skills and culture; and that this can be nurtured through the development of connected, resilient local systems into the global market.

A final report was submitted to the Vietnamese Cleaner Production Centre, the European funding bodies and DELFT University (Netherlands), while the workplace furniture designed and produced by the six designers in various villages around Hanoi were put into a concept store in urban Hanoi. The Vietnamese designers in the group continue to work with sustainable development imperatives in mind, and champion this approach within the design sector in Vietnam. This research contributes to an ongoing umbrella project to integrate sustainable practice into the design, manufacturing and engineering sectors in Vietnam, in partnership with TU DELFT in the Netherlands. The project faces an uphill battle because Vietnam is still in various stages of development and sustainability is not a priority (while feeding your children is). Consequently it is important to identify what sustainability means in a local context, rather than applying Western ideals, refocusing on common factors such as family, community and cost efficiency. Support for and continuation of this type of exploratory project is incredibly important as a means of establishing new sustainable methods of producing and consuming that also deal with the reality of the everyday and the local systems at play.

The Future Living Studio team

The Future Living Studio is a Sustainable Product Innovation Network (SPIN) project in partnership with the Vietnamese Cleaner Production Centre (VNCPC), United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP), and the Economic Development Program – European Union SWITCH ASIA.

Project Managers:

Shauna Jin/Astrid Hauton (TU DELFT/SPIN)

International Designers:

Michael Schuster – Industrial Designer (Berlin)

Audrey Charles – Textile Designer (France)

Philippa Abbott – Strategic designer (Australia)

Local designers:

Tran Hoang – Interior Designer

Nguyen Thu – Architect

Nguyen Ha Phuong – Architect

Craftsmen (Thanh Dat):

Mr Lung – Master craftsman and factory owner

Mr Hung – Master craftsman

Mr Thanh – Master craftsman