Reimagining the Gaybourhood

I still remember the first time I set foot in a gay bar. The smell of the beer-soaked carpet, the sexually charged glances from other men (‘I haven’t seen this kid before’) and the sequins falling from Pollyfilla and Bumpa Love as they negotiated the tiny island stage at The Peel in Collingwood. I felt strangely at home. Queer places are gathering places. Over time, they have enabled me – and other queer people across the globe – to articulate identity and foster community connections, building a sense of family.

Our relationship to the places we love can become an important foundation of identity. There is a sense of shared social value inherent in all places, often with overlapping meanings to multiple communities. In her influential discussion paper, ‘What is Social Value?’, heritage expert Chris Johnston cautions: “[I]n our everyday lives we may be largely unaware of the deep ties we have to place, only to be made so aware when we have to face up to its loss”.

When I begun to notice the pattern of closure of numerous gay venues across Melbourne (such as The Market, The Xchange and The Greyhound Hotel) over the last 10 years – I started to feel this sense of loss myself. Some of the bars resumed under new (straight) management, others demolished for residential development. Small as they may seem, these incremental changes to the ‘gaybourhood’ have had an accumulative impact on the gay geography of the city. Confronted with this loss, I embarked on research to uncover what role the heritage planning system plays in protecting places of cultural importance to Melbourne’s queer communities. What I found is that this phenomenon is larger than local – the queer fabric of cities around the world is on the demise.

Gaybourhoods are queer-friendly neighbourhoods, often anchored by gay bars, clubs and institutions, but also including appropriated liminal spaces such as the surrounding streets, piers and public parks. These places and spaces are most commonly acknowledged as focal points of LGBTIQ community activism throughout times of political and social hardship, particularly in the latter half of the twentieth century when these communities were most mobilised in activist efforts in response to social inequality. They are recounted by historians as crucial incubators to queer political and social movements, such as Sydney’s Oxford Street and San Francisco’s the Castro in during the 1960s and ‘70s. The resistance against police riots which occurred at the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village, New York in 1969 is seen as one of the most powerful moments in the gay liberation movement throughout the United States. The lasting memory of these efforts is still celebrated there and pride celebrations around the world, such as Sydney’s Mardi Gras, often centre around historically important gay venues or neighbourhoods.

The conversation has changed in recent times, however. Economists and researchers such as Richard Florida and David Bell have reframed ‘gaybourhoods’ as a sign of cosmopolitan urbanity, in turn boasted by city governments and exploited by big business as a way to the ‘pink economy’. The cynical view is that gaybourhoods have lost authenticity and vitality, as well as social relevance. Sydney geographer Brad Ruting has suggested that queer culture has evolved towards a more integrated relationship with the broader community; perhaps queer places hold less relevance to today’s LGBTIQ identifying people. His research identifies a growing disillusionment with ‘gay scenes’ and an increased use of internet dating platforms, which has shifted the geography of queer community out of a central gaybourhood model and into many dispersed pockets across a city. In 2011, after several gay bars shut their doors on Commercial Road in Prahran, Tom McFeely, owner of the Peel Hotel, told journalists he often heard people in the community say, “Oh, we don’t need gay bars any more”, anecdotally reflecting this change.

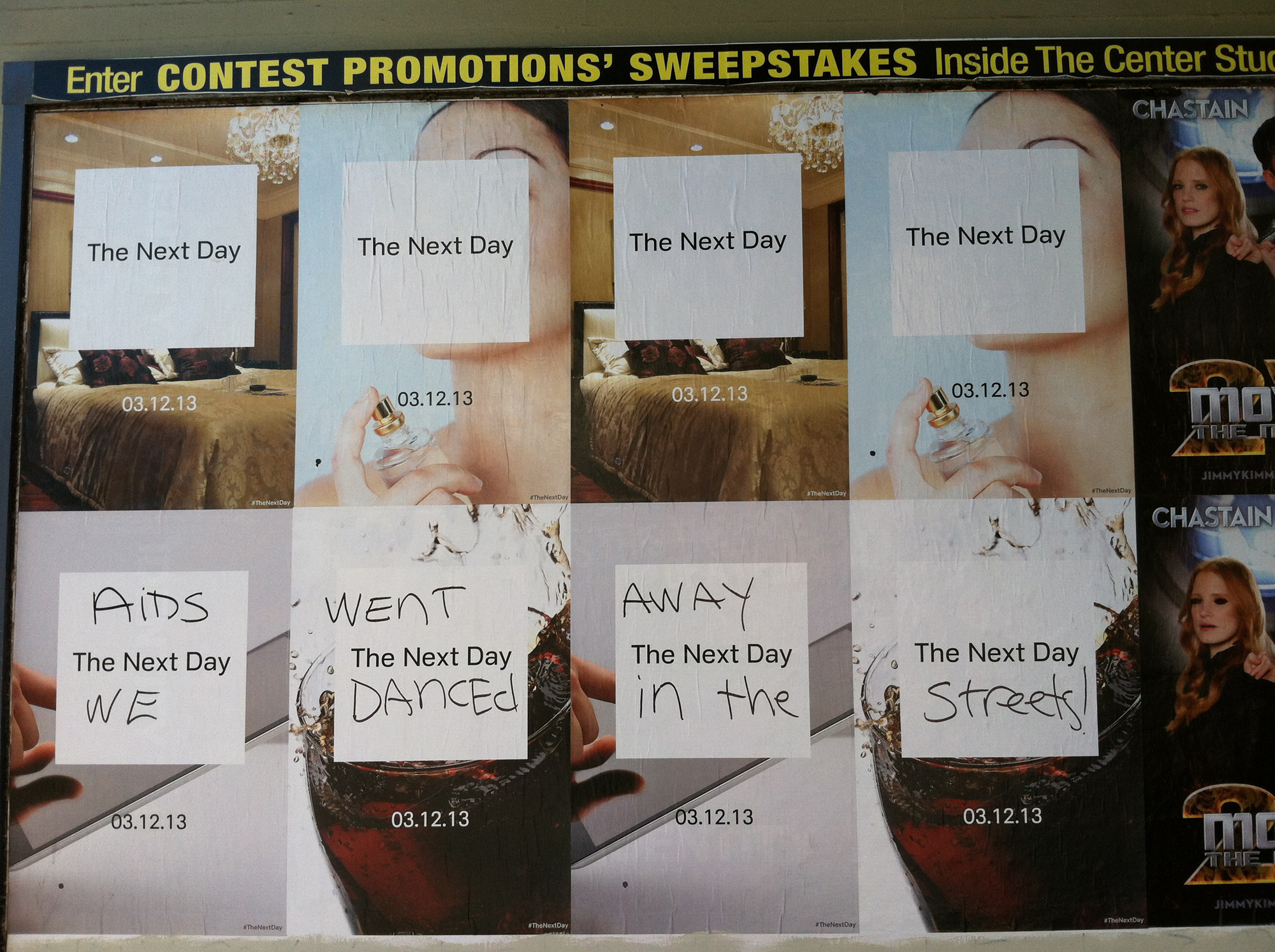

Memorials and plaques have become one way of celebrating and remembering the lost queer community. Sydney, Tel Aviv, Amsterdam and Berlin all host eminent memorials to the LGBTIQ victims of persecution – often near an existing, gentrifying queer precinct. In Melbourne, Keith Haring’s 1984 mural is protected under the Victorian Heritage Register, partly due to the social significance of Haring’s prominent status as artist queer activist in raising awareness of the AIDS crisis during the 1980s through his art. Nick Henderson from the Victorian Gay and Lesbian Archives tells me that “…plaques and memorials aren’t the only way to remember and celebrate the city’s queer history”. His 2015 exhibition Out of the Closets, Into the Streets: Histories of Melbourne Gay Liberation told the stories of Melbourne’s underground gay community, that found its voice in the early 1970s. He tells me that local stories also live on through Facebook groups like ‘Lost Gay Melbourne’ and its Sydney counterpart, which act as community connectors, allowing those who once sought refuge in gay-friendly urban spaces to share memories, and foster positive intergenerational exchange within the community. NYC’s West Village even has an Augmented Reality queer history app – allowing users to relive the former flair and important social history of the district in situ, guided by prominent 1980’s video artist Nelson Sullivan.

Preserving gaybourhoods as they are is a complex balance of urban planning and cultural progression. Very few examples of government-led attempts at this exist. At the 2015 Australian Queer Histories conference, queer historian Richard Peterson identified that only two gay venues in the world hold heritage protection, The Stonewall Inn and London’s The Royal Vauxhall Tavern. Although governments and communities have tried, heritage protection is limited in its power to maintain the ‘fabulousness’ of a place. While the built fabric of a place is important, heritage protection alone can’t ensure that a tenant who wants to run a queer-friendly business will move in, or be able to afford the rent. In 2011 Ottawa’s mayor declared two intersecting streets in Downtown as ‘The Village’, a municipal government designated queer neighbourhood. This move to incentivise a central gay destination came a time when queer media was reporting that North American cities were losing their gaybourhoods rapidly, challenging the dominant discourse that gaybourhoods were destined for decreasing relevance in the face of commercialisation, gentrification, and advances in gay rights.

In an Australian first, The Victorian Government’s new Pride Centre is set to open in St Kilda in 2020 and aims to bring the “LGBTI community together in a single and powerful space”. Staging a panel discussion at Melbourne’s NGV in 2017, Monash University’s Space Gender Communication Lab, XYX Lab, floated the notion of ‘queer architecture’, prompting a question: “Perhaps this is buildings for queer people and their particular needs and desires?”

Today, we can easily take the gaybourhood for granted. In many corners of the world queer-identifying people continue to be politically and socially persecuted, creating queer refugees seeking a safe place to live. Even at home, young people in regional areas still face hardship often with no safe place to flee to. In the panel discussion at NGV, architect and musician Simona Castricum shared the experience of navigating through a space like an airport as a gender-nonconforming transgender woman feeling “.. inspected and judged at a series of checkpoints”.

Nurturing a queer community, however, requires more than just the bricks and mortar. The memories embedded in queer places go above and beyond newly commissioned architecture: shared histories take generations to plant roots and grow beneath a city. While we accommodate population growth and let neighbourhoods change and evolve, city planners should consider what goes beyond zoning – the importance of our queer places. Perhaps to queer architecture is to reimagine ordinary places as inclusive places for queer people, rather than confining the community to the closet of a queer-friendly enclave. The city must be reimagined to nurture the next generation of queer citizens, whilst respectfully acknowledging those who have fought hard to afford us the rights we enjoy today.

A huge thanks to Sam for sharing his research on heritage protection of queer spaces with us, and to the queer community around the world for documenting their beautiful places.