Sunyata: The Poetics of Emptiness

Sunyata (Sanskrit; Pali: suññata) translates into English as Emptiness and Voidness. It is the noun form of the adjective sunya or shunya. Sunya means ‘zero’, ’empty’ or ‘void’.

The Indonesian archipelago is a vast country, one of the most diverse in the world in terms of ethnicity, natural resources and topography. The process of preparing our installation for Indonesia Pavilion at Venice Biennale of Architecture 2018 was also a journey to understand the abstract complexities, as well as the banal and pragmatic dimensions, of building practices in Indonesia today.

In Sunyata: The poetics of Emptiness, we wanted to assert a particular design approach based on everyday architectural practices in Indonesia, where it is common for the craftsman and the architect to work together. Throughout the archipelago, building practice is a communal activity – for the people, and by the people. The architect or designer is more of a conceptualiser than a project leader or sole creator. We wanted to embrace and revisit this deeply rooted building practice and reformulate it into a design provocation.

The starting point for Sunyata was an awareness that a practice of celebrating ‘emptiness’ exists in various building practices throughout Indonesia. Emptiness is a concept strongly rooted in cultures and religions throughout Asia. The interpretation often varies, yet the essential understanding is the same: emptiness is understood as an active entity, an instrument that injects order into the void. Place-making operations across Indonesia, encapsulated in various traditional building methods, share one feature: the void is the crux of spatial organization.

Architecture is an instrument of metaphorical liberation from chaos: it manifests as a ritualization that transforms ‘chaotic’ space into an ‘orderly’ space, through different methodologies produced by different ordering systems. ‘Petungan’ is one such methodology: a Javanese numerology-based divination system applicable to all aspects of Javanese life, which they believe will bring good order to everyday life. Based on three components – cardinal direction, cultural index (a value embedded in the Javanese calendar day), and a dimension of the user’s body part – it is a traditional numeric system containing not only information on place and time, but also on building material, colour, proper use and so on. These components are calculated via a traditional algorithmic formula, which prioritizes the scale and the proportion of the space, rather than the building shape.

Consequently, building complexity follows the expansion of the space, rather than the other way around. The space is constructed in a centrifugal manner, from the inside towards the outside. Building a house for a Javanese can be understood as the construction of a void (ambiance) rather than form. An enclosure is an instrument to manage building porosity: it controls the amount of solar heat, daylight, rainfall, and humidity, affecting the comfort of the inside space. The [external] shape is irrelevant to the [internal] ambiance produced by the house.

‘Emptiness’ is a not a void, but a quality present within the void. For the Javanese, it is manifested by controlling the scale, proportion and tactility, which establishes a dialogue between the space and the user’s body. As a spatial quality, emptiness is timeless. At the same time, it is grounded in a particular context. The construction of emptiness requires a void and two components: porosity and an event. In order to work, the volumetric space of the void must be programmatically dominant; it has to function as the primary anchoring space.

Such a composition might yield two types of spaces. The first is concentric, proportionally tall, with a play of light and shadow coming primarily from the top. Sumur Gumuling or Gumuling Well at Taman Sari, Yogyakarta is an epitome of this model. A royal meditation place, it is relatively isolated from its environment. The meditation platform at the centre is a floating structure, the only connection to its surrounding three step bridges. Neither ceiling nor roof covers the platform, and the huge opening creates an experience of awe. Rain, sunlight, shadows and breeze flow freely, creating a tranquility and, simultaneously, a suspension.

The cone-shaped chimney of Masjid 99 Cahaya diffuses daylight into the building. The architect deliberately positioned the only entrance into this mosque low and narrow, beneath the eaves. The dimness of the interior creates a spectacular contrast with the diffused daylight streaming in through the roof.

Similar spatial logic is at work in Perpustakaan Tjahjono private library, also a place designed for spiritual retreat. To enter the library, one must use the spiral ladder in the centre of the room. The library itself is on the second floor; the radial arrangement of bookshelves and the position of the ladder emphasize the verticality connecting the ground (the earth), and the light from above emphasizes the concentric volumetric space.

The second type is created by intense human movements and interactions. Whereas the first type is a space of ritual, the second is a space for living, characterised by a strongly linear space and a flow of daylight and air from the sides. It is found in vernacular domestic architecture where a huge roof covers almost the whole building, such as the Rumah Betang Nek Bindang family house. More than one family resides there, each occupying one big room, arranged side by side along the long corridor. The corridor is the backbone of this type of house, and central in its spatial organization: this is where events and activities happen.

Rumah Butet Kartaredjasa and Rempah Rumah Karya, a house and an office respectively, are two buildings of this type, composed of multiple voids and sheltered by huge roofs. Another extraordinary exemplar is Gereja Maria Assumpta. To enter this church is to follow the procession meticulously planned by the architect, from a narrow, low-ceilinged corridor into the main hall. The space is not suddenly and dramatically transformed; its gradual transition is finely controlled. The ceiling, which slowly rises higher as the visitor approaches the main hall, sets an elegant spatial procession.

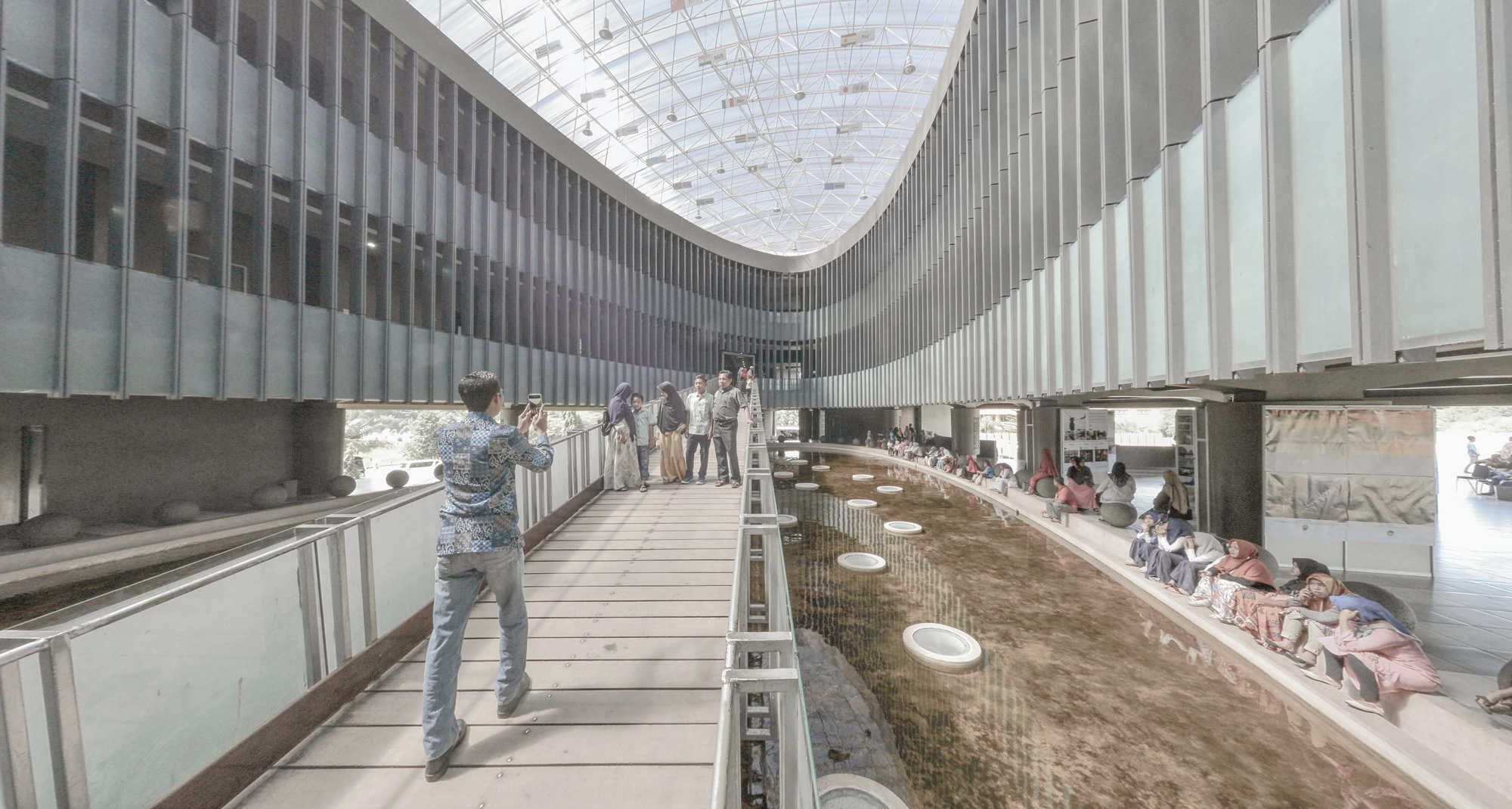

The third model is a combination of the previous two: the light comes primarily from above, the emphasis is on the height, but the space does not have an imaginary vertical axis. In this model, user movement enhances the horizontality of the spatial organization. Umbul Warungboto in Yogyakarta is a perfect illustration of this unconventional volumetric space. The linear pool that splits the space right in the centre plays a prominent role in setting up the ambiance of this royal bath villa. This horizontal gesture signifies domesticity, but at the same time its opening to the sky amplifies its meaning as a ritual space.

Museum Tsunami Aceh, Wisma Garuda, Jonas Studio and Artotel Sanur are all buildings that employ a linear corridor that runs through the centre of the building as the backbone of the program. The ramp that splits the void in the Museum Tsunami Aceh is so deep that it assumes monumental significance. In Jonas Studio, in contrast, the corridor connects voids on different levels, letting the breeze flow through the inside of the building.

The history of design in the West can be understood as a story of experimentation and speculation: cracking the mystery of design is the primary goal. Leon Battista Alberti’s works ‘De Pictura’ (1435) and ‘Description Urbis Romae’ (1404-1472) demonstrate this pursuit for precision in the art of mimesis. ‘De Pictura’ is written without a single illustration. The three chapters in the book focus on three ideas: understanding light, mathematical method in painting, and the importance of history. Alberti’s elaboration of each of these ideas aims to provide a systematic method of reproducing reality onto canvas. In Asia, such a history of experimentation does exist, but it is subtle: the cultural emphasis lies in embracing the enigmatic quality of nature.

In Indonesia, making a building is considered a cosmological weaving practice, which requires a good understanding of pattern, disseminated verbally. The question is, then: how can we employ this traditional building practice in our contemporary world? Nowadays, no contemporary architect in Indonesia seems to employ traditional methods. Yet the practice of using the void as the crux of spatial organization is still present.

We wanted to weave these stories about void – of the old way and the contemporary way – to posit the fundamental question of form in architecture. Louis Sullivan’s maxim ‘form follows function’ is commonly considered a statement on the primacy of utility over the aesthetic. But this logic is not universal. In Southeast Asia, form is understood as a trace of becoming. Form is a stage where everything fits in its place, not a physical condition but a mental stage – neither the initiator nor the result, but process itself. In Petungan building practice, the building as a physical object is unimportant; the emptiness is the form, a becoming-space which is a manifestation of cosmic harmony. We believe this understanding of form is present throughout the Indonesian archipelago, and our intent in Sunyata was to elucidate a different place-making operation, one probably untraceable in mainstream architectural and design history.

Our installation at Venice Biennale 2018 aims to be a representation of Emptiness on a metaphorical level. Compared to the common, ‘authoritative’ construction elements such as column, wall and roof, paper is a material of almost nothing: it embraces the site and the gravity as determining forces to construct the form and the space. The paper slices the space vertically. No intervention in the space above: it is a pure void. The vast space allows a dialogue between the space and the human senses. Eliminating typical architectural elements creates subtle disorientation, preparing the mind and the senses to listen to the pre-recorded ambient sounds. This dialogue between the senses and the void results in a distinctive spatial quality of Sunyata, ‘the place of Emptiness’: it is a space constituted of people’s subjectivity – their memories of life, space and sensations – which are treated as the main design component.

For the Javanese, the form is manifestation of a spiritual quest of finding oneself. By exhibiting a void, we want to create an analogy of how form can be presence – by placing the human being as its primary spatial agent and simulating a way of form-finding through one’s spiritual journey.

Thank you, David and Ary, for one of the most remarkable experiences in Venice this year. Big thanks also to Tjaša Kalkan for her exquisite photography. Unless otherwise mentioned, all photos are used courtesy of Ary Indra. You can learn more about Sunyata on the official website, or visit it in Venice before November 2018.