Owner Occupied

Geoffrey London: There are many models of building and living collectively, such as co-housing and baugruppen. Can you define these models?

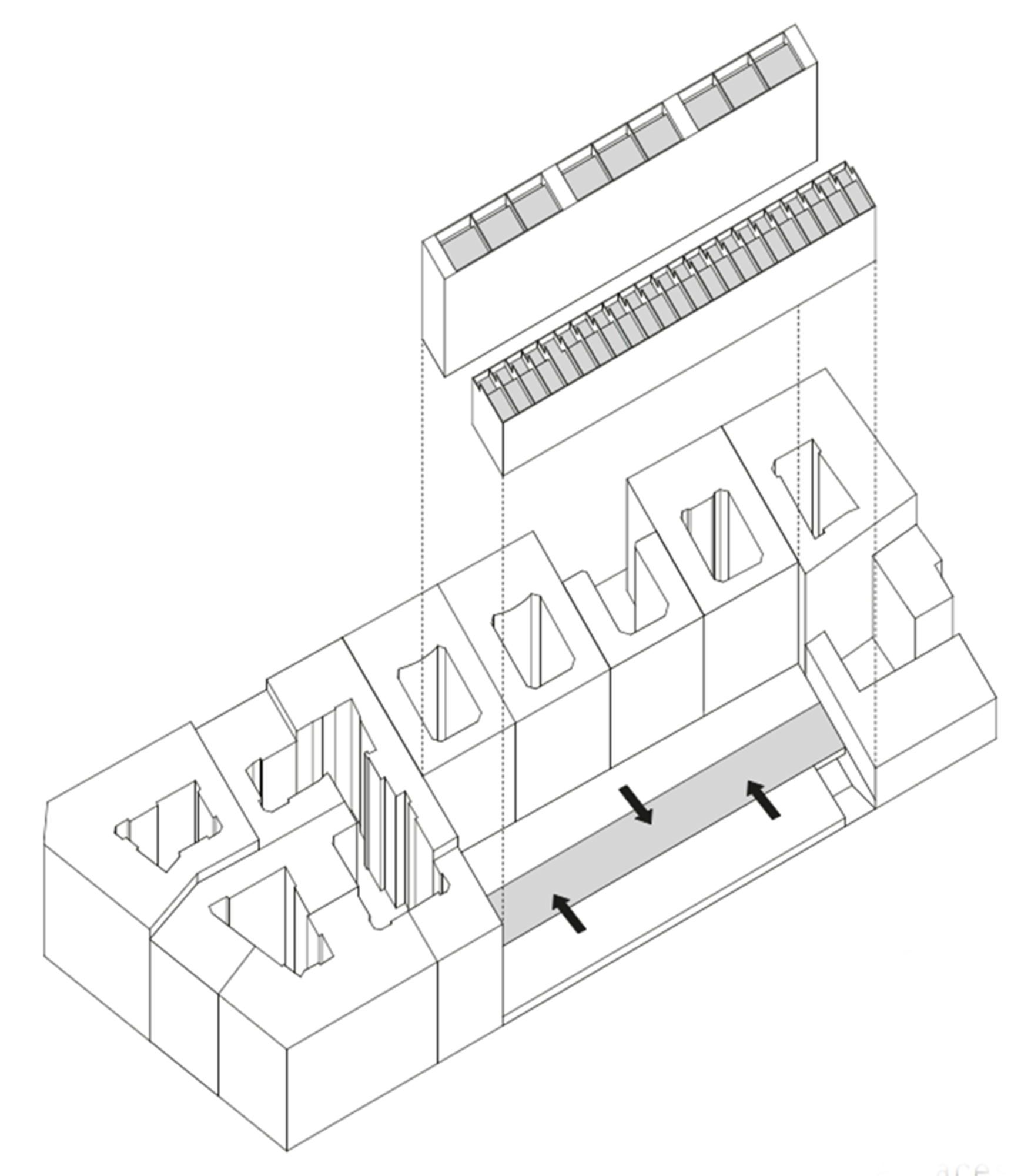

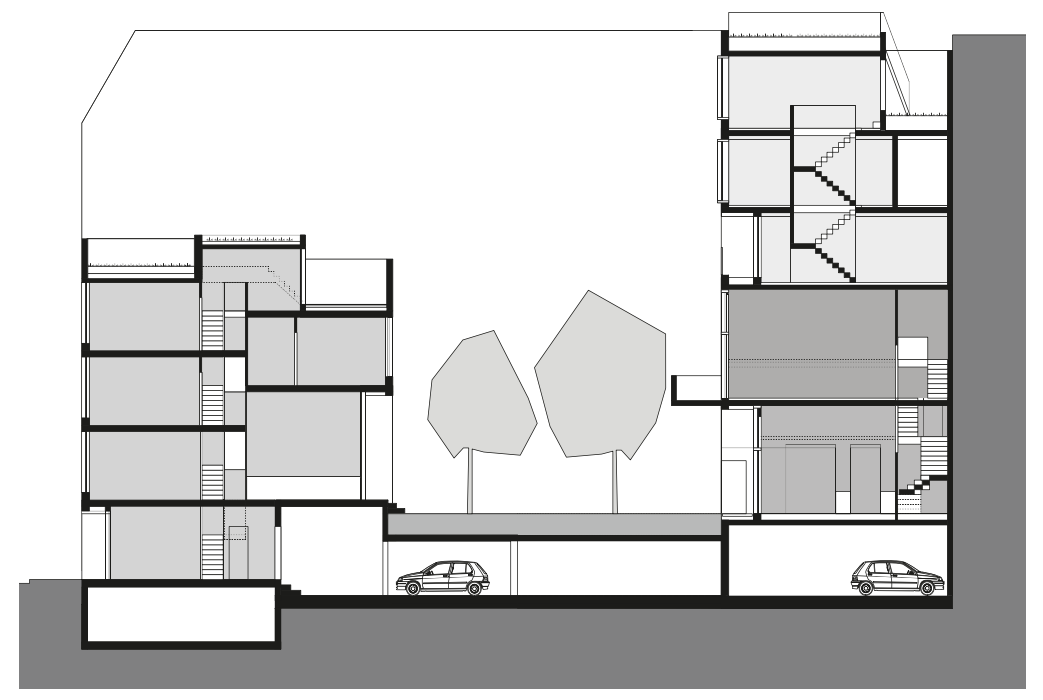

Kristien Ring: Co-housing, as far as it is understood in Europe and the United States, has a long history. It is not only about living in the same building. The act of sharing spaces, meals, routines or chores defines a co-housing project as a community. Sometimes they operate on an ownership-based model, sometimes they are associations. Baugruppen [German for ‘building group’] is an ownership-based model, but it’s pragmatic. The development is design driven, and co-initiated and co-created by an architect, together with future users. People come together in order to create their own homes, but they do this as a group on more urban sites. They buy the site together, contract the building together and share facilities, but they don’t necessarily share meals. Often they decide at the beginning what they would like to share.

GL: What was it in Berlin, in particular, that prompted people to adopt this model?

KR: People were not finding apartments on the market that suited their needs or tastes. For example, there were young families that didn’t want to move outside of the city. They were looking to keep their urban way of life, but needed to expand. People were also looking for apartments that could adapt to changing ways of life in the future, so as to avoid the need to move, and they wanted to be surrounded by good neighbours. At the same time, there was a slow market. Many architects in need of commissions recognised potential in this set of circumstances. Architects did designs for available building sites and found many people with similar needs keen to get together to build. At first we thought of it as a stacking of single-family homes.

GL: To what extent is amenity shared in baugruppen?

KR: When it first started they shared very little. But now, through this process, they have become more accustomed to the idea of sharing more with each other. The more pragmatic view is that the people have their own apartments, and that’s the centre of their life, but they also share things that make their life in the city better, such as common spaces where children can play in the afternoon. When the kids grow up, they use spaces for different purposes.

GL: How effectively has the concept of baugruppen evolved in cities outside Berlin?

KR: Other German cities, such as Hamburg, Freiburg and Tübingen, have seen the benefit of this model in redeveloping brownfield sites, and often see baugruppen communities as an incubator as they display so much initiative in terms of ecological and sustainable building, and they have social benefits. Because the group already knows each other well before they move in, you get an instant close-knit neighbourhood. These cities require at least 40 per cent of their sites to be developed this way and support them by reserving land (at market prices).

GL: Relative to conventional apartment delivery, what advantages are there as a result of the baugruppen process?

KR: The built architectural quality of these projects can exceed that of anything else on the market. They also have an emphasis on green spaces. They activate the street frontage with mixed use. They build to a really high quality at affordable prices. It’s amazing how much the groups save by being their own investor. The projects cost about 20 per cent less than what’s offered in the developer-delivered marketplace. They don’t need an external organisational structure to manage the building [for example]. There’s a greater trust. There’s a greater willingness to share than in a place with fewer owner-occupiers, because they’ve got to know each other in the process.

GL: This emerged from a pragmatic desire to get a better product rather than from a utopian desire to share?

KR: That’s right. It’s just common sense. [Laughs].

GL: How many projects are there in Berlin that demonstrate these outcomes?

KR: Over the last twelve years over 400 projects have been built with well over 5,000 apartments.

GL: In Berlin how have the more traditional developers responded to the baugruppen model?

KR: They were sceptical at first, and then they saw it working. They realised they need to embrace it, and offer something similar. They were surprised because owner-occupiers came with huge demands. They wanted regular meetings – the developers were unprepared for this system. It’s time consuming. In that way they gave it up. They realised their model is something different. It’s healthy to have diversification of the market. And it’s not eating into their profits. It’s for people who wouldn’t be able to buy on the market and wouldn’t necessarily want to.

GL: Is there a role for developers in the delivery of baugruppen?

KR: Potentially. The developer could be an investor that secures the land and sells it to baugruppen, or they can lease the land, which reduces the initial cost of investment. A traditional developer could also provide project management services.

GL: What role do you see for government in assisting the formation of baugruppen?

KR: They need to recognise the potential of it as an incubator or a catalyst within new developments and make land available for baugruppen projects. Government can also help in the facilitation of baugruppen by having a place where people can gather, such as a website, so people can learn more about it and register interest if they want to. The website could inform people of differences in the various models so people understand the alternatives on the market. A demonstration project would also show people what’s possible. They could even support a third party that consults with baugruppen, such as in Berlin where the government is not sanctioned to officially consult itself.

GL: In Berlin was there any need to change regulatory requirements to allow for baugruppen to develop?

KR: No, there were no changes needed. Banks also found that it was quite simple, because the only pragmatic way is to give each party their own loan and, in that way, finance the whole group. In the end they pay stamp duty twice. This is quite a large sum, so it would be advantageous if that could be avoided.

GL: From what you have seen, what opportunities are there for this model to work in Western Australia?

KR: I think there is a huge opportunity not only in more urban situations, but also in the situation you have of densifying the suburbs. This would be much better done by people coming together to make their own decisions rather than selling to a developer, who just squishes in three badly done units. There’s huge potential there for people to take it into their own hands, and go in together with neighbours. In doing so, they could create a situation where they can live there too, which could be both rewarding and lucrative — particularly for the idea of aging in place. It’s often hard to imagine how a site or space could be used. Baugruppen brings in people with a lot of ideas about how they want the urban environment to be, and working together with architects helps get excellent design solutions. People make entirely different decisions when they are going to live there themselves.

*

This is the fourth in a series of articles we’re sharing from Future West (Australian Urbanism) – this time from the second and most recent issue. Future West is a print publication produced by the University of Western Australia’s Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Visual Arts. Future West looks towards the future of urbanism, taking Perth and Western Australia as its reference point.

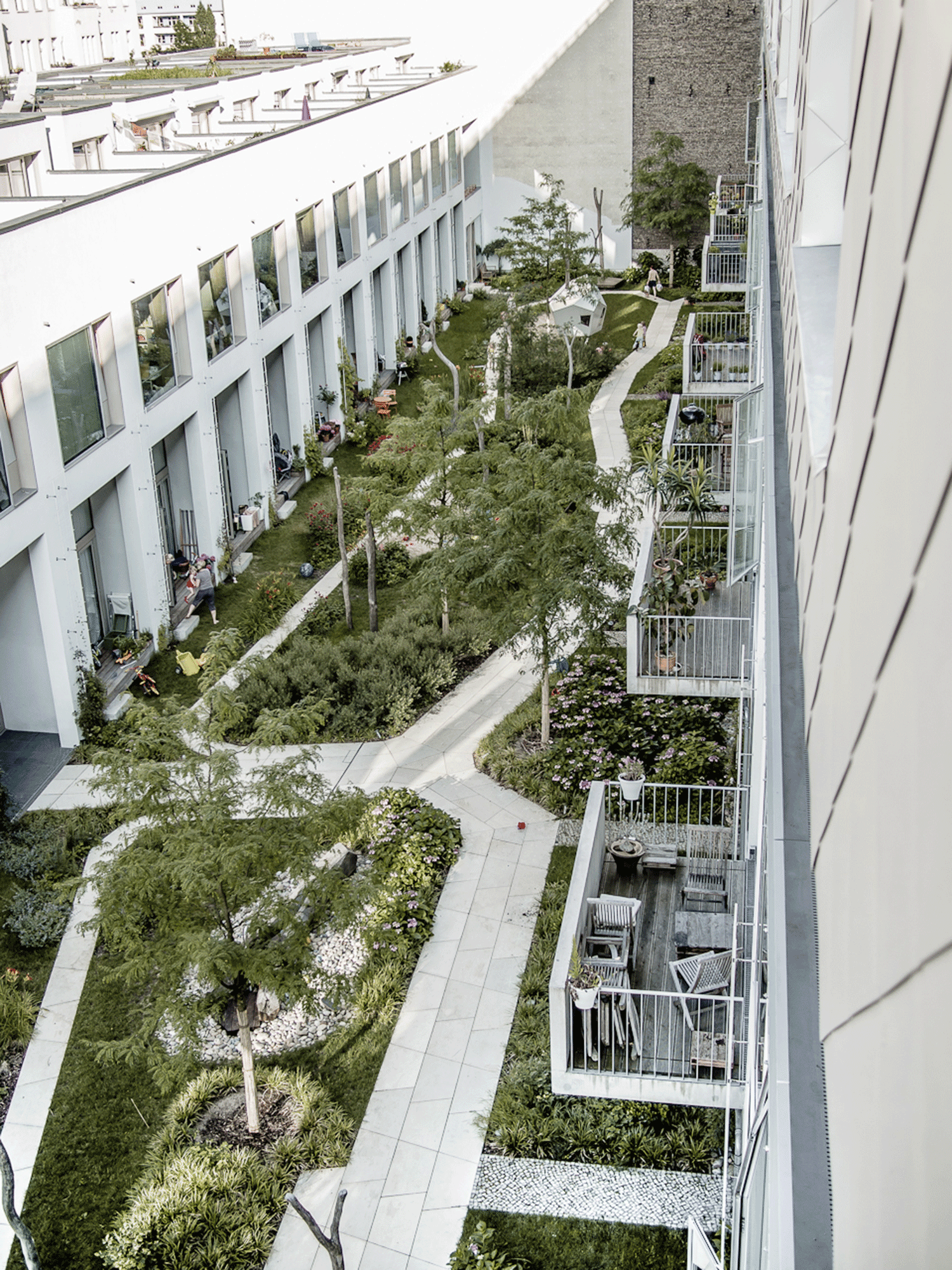

Original image: Big Yard by Zanderroth Architekten. Photo by Simon Menges.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

Kristien Ring is a professor of architecture and urban design at the University of South Florida, and principal of AA Projects interdisciplinary studio, Berlin. She was the founding director of Deutsches Architektur Zentrum.

Geoffrey London is a professor of architecture at UWA. He is a former government architect of Victoria and Western Australia, and a past dean and head of architecture at UWA.