Winter Park: Suburban Nature

Winter Park: a place where small scale suburban life co-exists harmoniously with the neighbouring flora and fauna. A pioneering feat of its time, Emma Whiffen explores this innovative 1970s design in Doncaster, which focuses on landscaping by integrating the surrounding parklands and bush into the housing complex as a shared space for its residents.

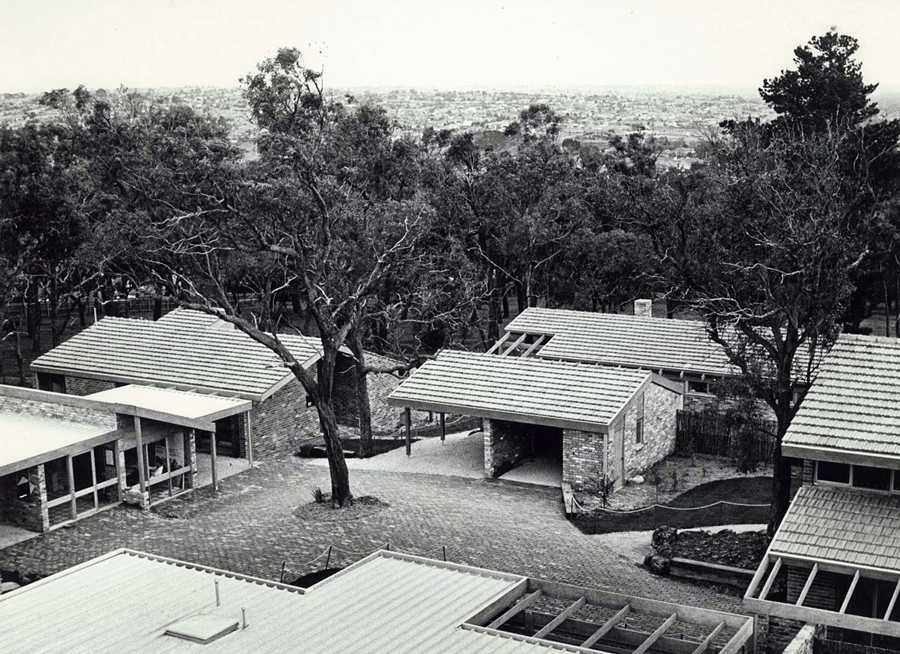

Winter Park housing estate was developed in the early 1970s, at a time when Doncaster, then located at Melbourne’s north-east metropolitan fringe, was quickly being converted from native vegetation, farm plots and orchids to a homogenous grid of low-density housing subdivisions.

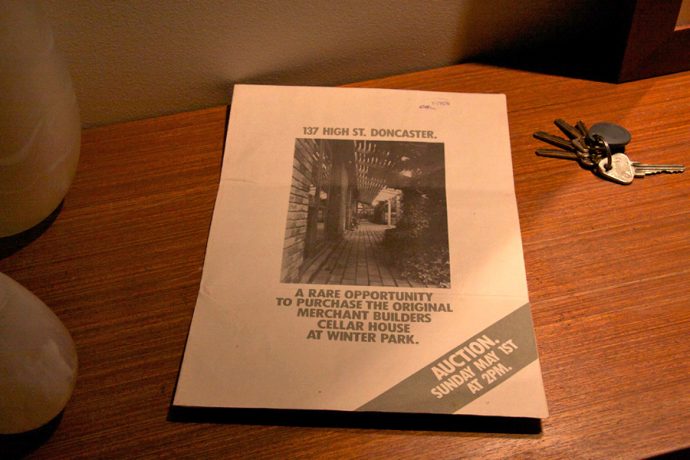

Merchant Builders – one of Victoria’s most influential developers who pioneered architect-designed project housing of the 1960s – saw the growing area as an ideal place to test their new prototype for suburban living. Founders David Yenken and John Ridge busted the dreary template of the rectilinear quarter-acre allotment, to put landscaping on equal footing with contemporary design. Architect Graeme Gunn, with landscape architect Ellis Stone, were engaged to demonstrate this new typology; commonly referred to as cluster housing.

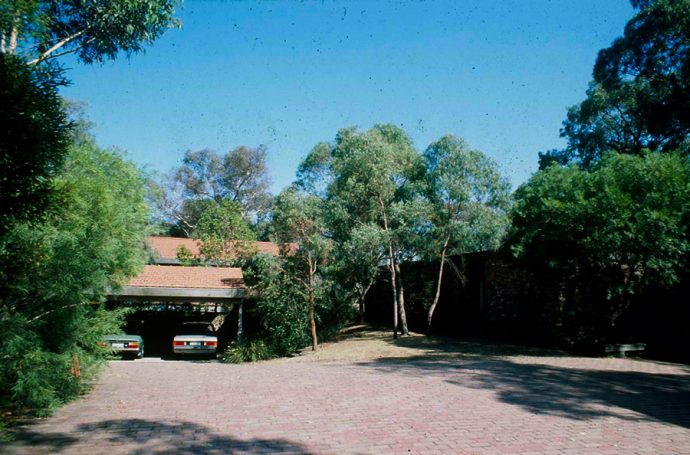

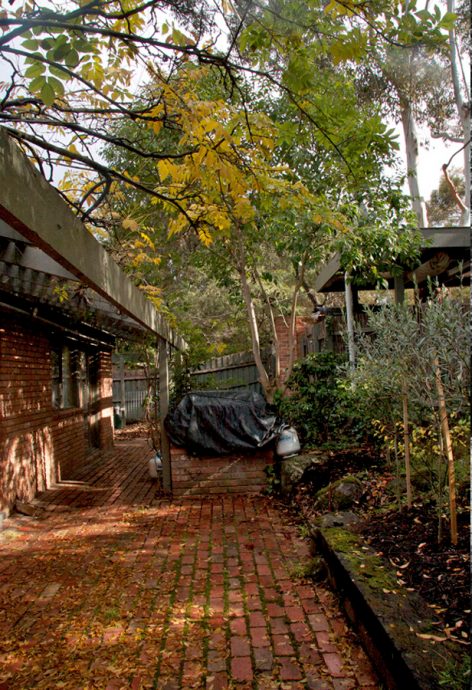

Winter Park is situated on 6-acres of land and is concealed behind a long, tall brick fence that breaks up the suburban regularity of busy High Street. The houses’ roofs peek from behind native bush; shrubs of banksia, Peppermint Gum and soaring eucalypts affectively camouflage this innovative housing subdivision. Communal brick-paved access courts and pedestrian paths separate the two groups of five houses that comprise the estate; a park is located at the rear that backs onto an earlier stage of the Winter Park development, also known as Timber Ridge. Here, the two groups of five houses are organised in a circle surrounding a central park. “A primary criterion for the selection of sites for display groupings was the landscaping quality of the precinct,” explains Graeme Gunn. “The notion of establishing a sense of place using the buildings and integrated landscaped open space was a major characteristic of our mutual aspirations to provide a planned environment different from and more beneficial than that which was generally on offer.”

Further to integrating dwelling and landscape, this new housing typology placed equal importance on building orientation, plan and materiality. It appears this theory has translated to reality, as many of those who live at Winter Park have done so for 20 plus years. One such resident is professional builder Mark Stivey, who, along with wife Lisa, daughter Charlotte and cavoodle Sasha, have called Winter Park home for two decades. “We were pleasantly surprised that it had a beautiful one-and-a-half acre park when we bought the property,” says Mark. “We used to have working bees four times a year, but strange enough, we’re the youngest family who live here … Most of the people are either retired or semi-retired, so now, most of the time, we pay a gardener to upkeep the grounds.”

Although Winter Park was marketed towards growing families, the social-economic ‘middle-upper class’ status of the surrounding area drove up Winter Park’s housing prices. “Most people with young families couldn’t see the value of buying into it because it’s probably 50 per cent more expensive than other similar sized homes in the area, and you’ve got all the extra gardens and parks which obviously adds to the cost of the place,” says Mark. “We could only afford it because we had one child.”

This sentiment is reiterated by Graeme, who cites the negative response from local council and the lack of enthusiasm displayed by bureaucrats as reasons for construction delays that affected the financial viability of the development.

The material palette of the Cellar House – where the Stivey’s live – is warm and restrained, and features a cosy fireplace with black slate hearth, limed pine ceilings and extensive glazing. The internal layout originally featured one living area and four small bedrooms, with built-in robes and adjoining amenities. As Charlotte grew older, the Stivey’s tweaked the original plan to suit their changing lifestyle. “The concept of the Master Builders’ places was that you only slept in the bedrooms and you spent most of your life in the rest of the house. So we ended up converting one of the bedrooms into a separate lounge and study for my daughter – who strangely never comes out of there,” Mark teases. “So now we have two, more open plan living areas.”

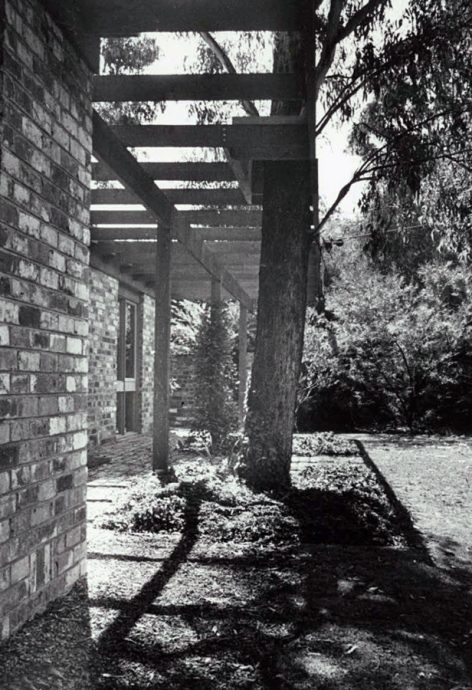

The kitchen and lounge areas are orientated outwards to engage with the private courtyard, thereby maximising access, solar orientation, day lighting and views. “Most of the houses’ living areas face north,” explains Mark. “They have battened pergolas and additional shading with deciduous vines which stops the hot summer sun coming through your window, but lets the low winter sun come in and warm the floor.”

Over the years, the gardens have generally remained in their original state, apart from some roses planted by a neighbour, and the addition of tea-tree fences to loosely separate the properties. The external finishes are uniform across all dwellings and include timber battens, brick terracing, concealed plumbing and Hawthorn Pink brick walls. “This place has very, very strict guidelines – even before it was Heritage Listed – with fencing, gardens and external painting. So you have to maintain the exact same colour – its called Swamp Gum – on all the outside timbers and windows,” says Mark. The materials are robust, with an earthiness complementary to the gardens. The hard landscaping is characterised by an assimilation of materials, with rocks, timber edges and sleepers placed to bleed into the established Australian natives and remanent bush at the property’s rear.

The communal park is a result of Merchant Builders’ seminal departure from the traditional method of suburban subdivision. Although Winter Park provides a similar number of dwellings as a conventional allotment, the project was carefully planned to aggregate excess land to become shared open space. “The objective of Winter Park was to apply a more effective form of subdivision appropriate to the preservation of landscape features and topography of significance, as distinct from destroying them as an expedient method of producing land to build on,” says Graeme. “How often do we see wonderful portions of greenfield land marketed because of their unique features and then find, post development, that those topographical and landscape features, previously so aptly lauded, have been unceremoniously obliterated.”

The original landowner, Frederick Winter, was a farmer, orchardist and keen naturalist, who actively preserved the native flora and fauna on the Winter Park grounds (his original homestead dating back to the late 1800s is located three doors down and owned by a young family). “He left over 500 mature, indigenous trees; apart form where the houses were built,” says Mark. “We’ve got some ironbarks out in the park that are over 500 years old and we’ve got native bees in them, lots of possums, cockatoos, rosellas, kookaburras, sugar gliders and a family of ducks that visit every year, nest in our pool, hatch a batch of eggs and then they walk off – I believe that’s been happening for over 50 years.”

While the native fauna enjoy the proximity of the park, so to do the Winter Park residents. The recent addition of a table and benches, handcrafted from Cypress Pine sourced from Gippsland, has added more opportunity for neighbourly interaction, incidental meetings and conversation. “It’s been fantastic because – as nice as the park was – there was no reason to go there unless you were walking the dog. Now we have the table there during the summer months. Probably five months a year we all meet down there one or two nights a week and have a glass of wine and a bit of a barbeque, and you get to meet all your neighbours and the dogs can run around.”

The diversity and seamless connectivity of spaces at Winter Park forms a cohesive development that ultimately betters social connection and liveability for the residents. “One of the main factors in affecting the lives of those residing in Winter Park is the rational ordering of open space and the consequent optimisation of usage,” says Graeme. “The hierarchy of space from public – council road – to semi-private space – internal access and central recreation space – and then to private open space integrated with dwellings, offers a greater degree of controlled, useable and manageable space.” Rather than being separate domains, the outdoor and indoor spaces are interactive which contributes to the quiet yet important presence of Winter Park.

Feature image (top) by Kurt Veld, courtesy Gunn Dyring. To view more work by Gunn Dyring visit: www.gunndyring.com.au.